Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 8 Mar

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

This week, reporters from around China and the world — including many locked out of the country for years — have been flocking to Beijing to cover the annual Two Sessions, or Lianghui (兩會), of the National People's Congress and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. It’s a big fixture in the political calendar of the PRC and beyond.

In Taiwan, observers are parsing the language around cross-strait relations to gauge the likelihood of conflict. And in Hong Kong, local authorities’ determination to ram through more national security legislation for Beijing’s benefit is leaving residents weary of the new ways their lifestyles and livelihoods could be further threatened.

It is, in short, a tense and busy time for anyone covering the Chinese-speaking world or simply concerned about its prospects. We’ve tried, in this edition, to add something to the discussion around the Lianghui ritual, from the language around Taiwan to the push to Hong Kong’s Article 23, to the axing of the premier’s press briefing.

Enjoy, and have a happy International Women's Day!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

TRACKING CONTROL

Wrong Face, Wrong Time

China’s “Two Sessions” (兩會) are infamous for tightening security all across Beijing. This year, a small glitch in the latest security smart tech shows who the police have their eye on.

Entering Tiananmen Square to cover the annual political ritual, underway in the Great Hall of the People, a reporter for Hong Kong’s Ming Pao (明報) was flagged by facial recognition software as a potential security risk.

“Have you bought shares in Evergrande?” police asked the unidentified reporter, who recounted her experience in the newspaper. After she said no, the officer had a follow-up: “Have you ever gone to the National Public Complaints and Proposals Administration to file a petition?”

Eventually, officers realized it was a case of mistaken identity: the reporter happened to bear a resemblance to someone in the database — logged as a troublemaker, presumably, for joining other investors who protested to demand their money back when the real estate giant’s grim financial position became apparent last autumn.

The Two Sessions is a peak time for “petitioners” who descend on the capital from all over China to ask the central government to bring lower-level officials to justice. The Kafkaesque hurdles required to submit a petition, however, result in many staying for years and sometimes resorting to drastic displays to be heard. In his documentary Petition, director Zhao Liang (趙亮) filmed one desperate petitioner who, during the 2007 Two Sessions, scattered papers in front of the Forbidden City before being taken away by police.

REDLINES

Hong Kong’s United Front

The CCP's flagship theoretical journal Qiushi (求是), published by the Central Committee, is one of the key vehicles through which it publicizes its governing philosophy. And one measure of how drastically Hong Kong has changed in the past five years since the imposition of the national security law is the fact that it, too, now has something of a local equivalent: Bauhinia Magazine (紫荊雜誌).

In its latest issue, the magazine, which is owned by one of the biggest state-owned enterprises in Hong Kong, features a lengthy article by scholar-official Lau Siu-kai that well illustrates this role. In it, the Chinese University of Hong Kong professor and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference delegate coins a new phrase to describe the city’s “patriots-only” political scene: “party politics with Hong Kong characteristics” (香港特色政黨政治).

In defining this “very unique” system, Lau reaches some abstruse and counter-intuitive understandings of what democratic representation and political criticism mean. It’s a dynamic familiar to longtime readers of Qiushi: the regime-friendly theoretician applying an intellectual veneer to what is, at the end of the day, the raw exercise of power. But, in the process, it does offer a striking example of how thoroughly Hong Kong is being remade in the mainland’s image.

Look out for more on Bauhinia Magazine and “party politics with Hong Kong characteristics” in the coming days.

ANTI-SOCIAL LIST

The Martyrs VS Mo Yan

One of China’s most celebrated modern authors is in the firing line, and the ammunition is a hardline 2018 law on the protection of heroes and martyrs.

The Nobel Prize-winning writer Mo Yan (莫言) has irked extreme nationalist bloggers on the internet, one of whom, “Mao Xinghuo Who Tells the Truth” (说真话的毛星火), has requested a court order to remove Mo Yan’s books from circulation and force him to pay 1.5 billion RMB in damages to the Chinese people and “stop infringing on heroes and martyrs” in his stories.

The blogger’s four-page indictment, sent to the Beijing Procuratorate in late February, meticulously lists Mo Yan’s supposed offenses, including portraying members of the Eighth Route Army during the second Sino-Japanese War as sexually abusive, “beautifying” Japanese soldiers, insulting Mao Zedong, and saying the Chinese people have “no truth and no common sense.” An informal poll on Weibo asking netizens if Mo Yan should be criminally prosecuted received over 8,000 affirmative votes.

The case against Mo Yan might have relished in relative obscurity if not for former Global Times editor-in-chief Hu Xijin (胡锡进), who brought it to the attention of his 24 million Weibo followers by defending Mo. Mao Xinghuo successfully goaded Mo into a spat on the meaning of patriotism.

That a Weibo celebrity with 24 million flowers felt it necessary to engage with a hitherto obscure blogger with just 219,000 followers could show a level of panic, as some netizens noted in comments under Hu’s posts.

Stay tuned for more on this case next week on CMP.

CHAIN REACTIONS

The Khmer Connection

CMP has written several analyses in recent months about how China’s leadership has been working since 2018 to consolidate the external propaganda work of provincial authorities and local-level state-run media through entities called “international communication centers” (国际传播中心), or ICCs. The idea is for central powers to mobilize the peripheries to contribute more actively to the work of what Xi Jinping since 2013 has called “telling China’s story well.”

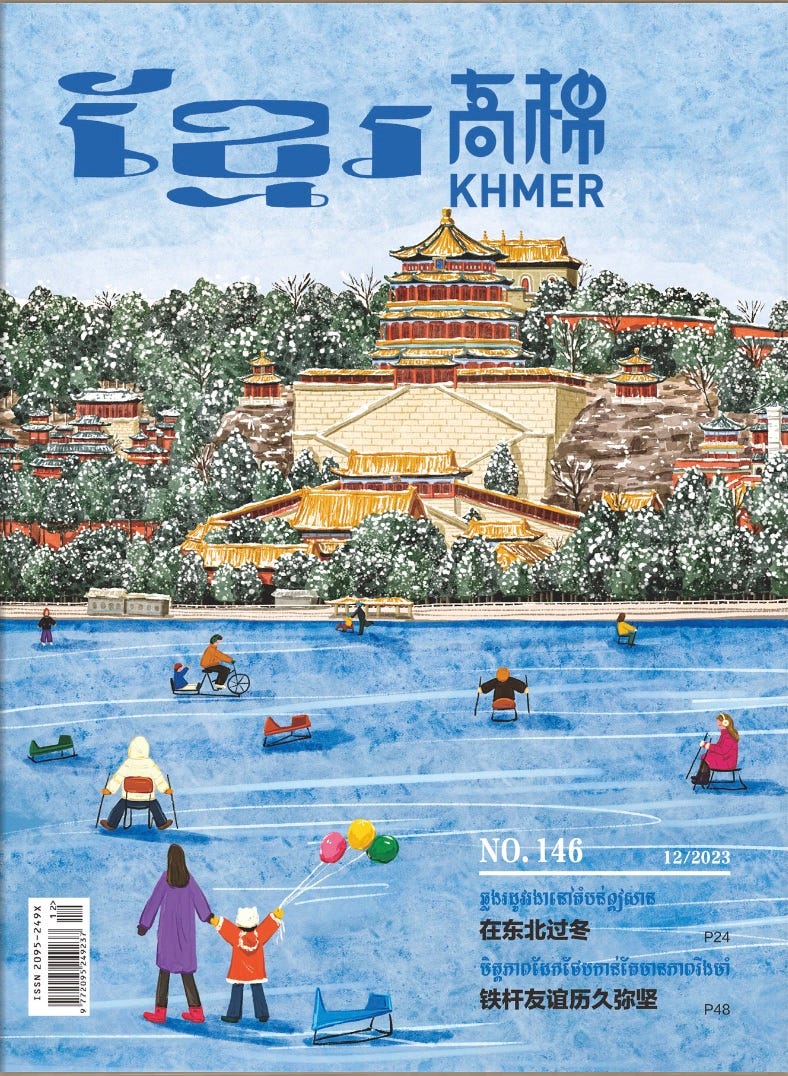

But it must also be said that the involvement of provinces and provincial-level media in foreign communication efforts is not exactly new. One good example of this is Khmer (高棉), a monthly magazine launched in Yunnan province in August 2011 in an effort to expand China’s media impact in Cambodia. The magazine, printed bilingually in Chinese and Khmer, the national language of Cambodia, opened a bureau in Phnom Penh in 2012. Attending the bureau’s launch event, the information minister of Cambodia said Khmer “fully demonstrated the high level of attention and support the Chinese government has shown Cambodia.”

The official government website Yunnan Gateway lists Khmer among its suite of publications directed at countries in Southeast Asia, which also includes Champa (占芭) in Laos, and Mekong River (湄公河) in Thailand. But the masthead of Khmer has also made clear since at least 2016 that it is published under the auspices of both the provincial-level government information office and the Information Office of the State Council. More recently, it has been published under the auspices of both bodies, but contracted by the Yunnan Daily Newspaper Group under Yunnan’s provincial CCP Committee, published and distributed by the Yunnan International Communication Center for South and Southeast Asia (云南省南亚东南亚区域国际传播中心).

In addition to Chinese culture and tourism, Khmer broadly promotes the benefits of Cambodia’s relationship with China. A feature at the center of the December 2023 edition promotes the Chinese-funded international airport in Siem Reap, bilateral cooperation on green energy, and the farming of ocean fish in a river valley in Xinjiang, “the region in China farthest from the sea.”

GOING GLOBAL

The Local Game of Global Propaganda

In January this year, executives from the state-run China Daily took the stage with Yunnan’s top provincial propaganda officials to launch a new regional media network meant to strengthen Chinese state narratives and agendas in Southeast Asia. The South and Southeast Asian Media Network is the latest move in a broader effort by China’s leadership to mobilize media and propaganda resources at the provincial level to achieve more effective regional and international messaging.

As we’ve detailed in previous research, provincial-level international communication centers, or ICCs, are spearheading efforts to “innovate” foreign-directed propaganda under a new province-focused strategy. In June 2023, provincial and city-level ICCs in China created a mutual association to better coordinate work nationwide. The process of integrating the ICCs both horizontally and vertically, including with central state media, has begun to emerge as a core strategy in the CCP’s remaking of its overall propaganda matrix.

Yunnan province is an important part of this new model. Addressing the gathering, Yunnan’s top propaganda official said the purpose of the network was to build “a platform and mechanisms for dialogue and practical cooperation between media of various countries” in the region, which shares borders with Myanmar, Laos, and Vietnam, and has strong and growing economic and development ties across Southeast Asia.

Read more in CMP Director David Bandurski’s latest article, “The Local Game of Global Propaganda.”

SOURCE CODE

A Potemkim Consultation

All of Hong Kong is lining up behind pending legislation, known as Article 23, that will further tighten the city’s national security regime — at least that’s the official story from the state-run Global Times, which remarked last week on the end of a public consultation period for the legislation. The close of the consultation period was perfectly timed for an “inspection tour” by Xia Baolong (夏寶龍), head of the State Council’s Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office (中央港澳辦), or HMO, and consensus in favor of the law was likely what Xia wanted to hear.

According to the newspaper, questions still hovering around the law are only minor quibbles to be resolved in due course. It quoted three experts in the field to substantiate this claim.

Stacking the Deck

Two of the three sources quoted, however, hailed from the same state-affiliated think tank: the semi-official, Beijing-based Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macao Studies (全國港澳研究會), which works hand-in-glove with Xia’s HMO. Association researchers are go-to talking heads that can be relied upon to back the HMO’s positions, and the two bodies are known to trade members with one another. Using a familiar CCP attack meme, association vice-president Lau Siu-kai, who is quoted in the Global Times story, has referred to protesters in Hong Kong as being urged on by “external hostile forces” [Learn more in the CMP Dictionary].

The third source was the chief of the Hong Kong Bar Association, a nominally independent and once-outspoken body of lawyers. But how could he dare to openly criticize this law when his predecessor was removed from his position, summoned by police, and hounded out of Hong Kong by a state media smear campaign after criticizing its forerunner, the national security law imposed by Beijing in 2020?

In past issues of Lingua Sinica, we’ve covered the atmosphere of fear prevailing in Hong Kong and the hollowing-out of its once boisterous civil society — specifically, how dozens of non-governmental organizations have closed since the implementation of the national security law and have been replaced with more compliant, pro-government counterparts. The organizations left standing, meanwhile, have learned to keep mum for their own survival.

Lau Siu-kai of the Chinese Association of Hong Kong and Macau Studies has again presented this fear as a positive scenario. “With these [existing] organizations folding,” he said in 2021, “there is now room for new groups which are more co-operative with authorities.”

The 99 percent level of public support for the law now touted by the government is a testament to their success — though less in uniting the populace than in cowing their critics into silence.

IN THE NEWS

Windows Open, Windows Closed

On the eve of China’s National People’s Congress on Monday, the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily called the annual session a “window on China.” Epitomizing the CCP’s penchant for rhetorical formulas, a page-three commentary by “He Yin” (和音), or “sound of harmony” — one of a number of pen names for group-written pieces at the paper representing the view of the central leadership — used three homophonic Chinese characters to describe how the NPC helped the international community better understand China.

[治 zhì] “governance” — The NPC, as a manifestation of what the CCP has in more recent months called “whole-process democracy” (全过程人民民主), helps the world understand China’s approach to governance. Are the annual “two meetings” really participatory? For a more critical and informed view, readers can turn to this reflection from veteran journalist Li Datong (李大同), who calls the two meetings a mere “spectacle.”

[质 zhì] “quality” — The NPC offers the world insight into the "quality" of China's economic development. The focus here is on “Chinese-style modernization” (中国式现代化), a catchphrase used since 2021 to encapsulate Xi Jinping’s assertion that modernization as pursued by China is equitable, peaceful and sustainable in ways distinct from that of the West.

[志 zhì] “aspiration” — The NPC shows China’s aspiration and willingness to cooperate with other countries through development initiatives like the Belt and Road. China, the People’s Daily said, will continue to promote peace and prosperity globally.

The Missing “Zhi”?

But the same day as the People’s Daily promoted the NPC as an open window on the nature of China and its development ambitions, it seemed to close the window shut on open communication.

Shortly after noon on Monday, the government announced that Premier Li Qiang (李强) would not hold the usual post-NPC press briefing. The marked the first time since 1993 that the the top official in charge of the nation’s economy had not taken questions directly from the press. This unusual turn of events only deepens concerns about China’s willingness to be open and forthcoming about the state of its economy and its policy-making.

China’s insistence of one-sided communication was comically epitomized during a press conference on foreign affairs with Wang Yi (王毅) by a clearly planted softball question about “telling the China story well” from Alobaidi Ameen Muneer Mohammed (方浩明), an Iraqi reporter from Dubai-based China Arab TV. The question gave Wang an opportunity read a prepared statement about how “China’s story is a story for all humanity.”

Given China’s suspension of the annual press briefing with the premier, and its focus on propaganda, we can add a fourth “zhi” to the People’s Daily list to mark a conspicuous absence of transparency.

[知 zhī] “to know” — This year’s NPC demonstrates to the world that China seems less and less willing to communicate openly about its politics, economy and society, even as it engages more deeply with the rest of the world.

NEWSPEAK

Talking at Cross-Straits

This phrase is in, that phrase is out. Given the opacity of Chinese politics, it is understandable that observers should rely on scrutiny of the official-speak of its leaders. But myopia and over-sensitivity are risks that can come with such close readings.

The most recent case in point may have come over the past week as regional and international media sought to read the broader implications for China’s Taiwan policy in a speech by CCP Central Committee member Wang Huning (王沪宁) to an annual meeting of top political brass to coordinate related policy for the coming year.

In the wake of the Taiwan Affairs Work Conference, which was held in Beijing on February 22-23, a number of media and observers noted apparent changes in tone between Wang’s speeches this year and last. In addressing the issue of “Taiwan independence” (台湾独立), the Chinese-language Radio Free Asia (RFA) reported, Wang had “elevated” his language from the simple word “oppose,” or fandui (反对), to the more energetic — and to some ears, more combative — phrase “resolutely combat” (坚决打击).

While reports like this are not off the mark in assessing the comments of senior officials in the context of Taiwan’s recent presidential election, understanding whether or not their language marks a real shift from the past requires a deeper and more careful look back on China’s official discourse.

Dig deeper with CMP’s latest article: “Talking at Cross-Straits.”

STORYTELLERS

New Frontiers in Foreign Propaganda

In its home market, the Discovery Channel has earned a reputation for never letting reality get in the way of a good story. Once home to respected wildlife documentaries and science specials, the network is better known these days for such colorful titles as Naked and Afraid, Deadliest Catch, American Chopper, and, of course, Shark Week. The network’s volte-face from education to entertainment has even become something of a pop culture punchline.

But what Discovery stands accused of with regards to China is no laughing matter. According to a group of US Congressmen, the channel is “whitewashing genocide” against the Uyghurs and other ethnic minorities in far-western Xinjiang.

In an open letter last month to the president and CEO of parent company Warner Bros. Discovery, six Republican representatives called World’s Ultimate Frontier — a new co-production between Discovery and CGTN, the international division of state-run broadcaster CCTV — “an obvious work of propaganda on the part of a totalitarian, adversary regime.”

Known in Chinese as “Entering Xinjiang” (走進新疆), the first trailer for the series features a cast of starry-eyed foreigners marveling at the sights, sounds, and tastes of the region, where the UN Human Rights Office says crimes against humanity have been carried out by the Chinese state. As mass detention, torture, cultural persecution, and forced labor go on behind the scenes, the hosts eat snacks and gawk at happy, dancing minorities.

Learn more about Discovery’s partnership with PRC state media in “New Frontiers in Foreign Propaganda.”

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Are Taiwanese Media’s Bad Old Days Over?

Last week, Lingua Sinica published a look back at an infamous kidnapping and murder case in 1997 that many view as a watershed moment for Taiwanese media, prompting the industry to reign in some of its worst excesses. This week, we spoke with Ming-Yeh Rawnsley, a scholar of Taiwanese media at SOAS University of London, about the legacy of the case.

Lingua Sinica: It's been suggested that the Pai Hsiao-yen case was a tipping point for Taiwanese media, their misconduct precipitating a slew of new regulations over professionalism and decent. Is this a fair characterization?

Ming-Yeh Rawnsley: I agree with this characterization. Journalists' behavior was the most appalling when reporting on Pai's case in 1997 and all simply for the sake of ratings and circulation. For example, getting in the way of police operation, which resulted in the failure of arrests; risking the lives of hostages by leaking serious and confidential information; sensationalizing all kinds of sexual, violent, indecent, bizarre and criminal elements of this case; offering the killers a platform of making public demand and self-publicity, and so forth. It was a complete disregard of news professionalism and ethics.

LS: Have Taiwanese media made substantial progress since then in becoming less sensationalist and more responsible?

MYR: Pai's case was a wake-up call for the press and press watchdogs. Media regulations have tightened and Taiwanese mainstream media have made some progress in their reporting. Generally speaking, it is less sensationalist and more responsible, especially compared to what happened in 1997. However, when major tragic or criminal cases happen, one may still find a degree of sensationalism which, for some, remains unbearable.

LS: What are some other pivotal cases since then you can point to as indicative of the state of media professionalism?

MYR: In 2005, when a 3-year-old child died in a kindergarten van, the director of the kindergarten was forced by the media to kneel down in public to apologize [Editor’s note: demanding public apologies from the subjects of ongoing stories is a nasty habit among Taiwanese media]. In 2014, when a series of random killings happened on the Taipei metro, the perpetrator was demonized in various ways by the press.

Nevertheless, there are also some more positive examples. For example, in 2015, a deadly dust fire occurred at a water park in New Taipei. Close to 500 people suffered from burns, including 280 with severe (40-80 percent and above) burns. The mainstream media largely exercised sensitivity in their reporting in order to avoid further damage to the victims and their families. They also distributed medical information about how to deal with burns, listened to medical workers, and helped to generate public support for the victims.

LS: What are some reasons for the lack of progress among some outlets since the Pai Hsiao-yen case?

MYR: If one feels that media progress has been underwhelming, there may be several factors to take into account: first, the ongoing struggle between press freedom and press regulation remains a difficult balance to achieve; second, media competition is only getting more and more intense; and third, the proliferation of media outlets and social media platforms blur the line between “mainstream media” and media as a whole for audiences.

"Mainstream media" — including newspapers and TV stations — have to abide by strict regulations like fact-checking, using credible sources, and avoiding unfounded accusations. However, social and online media don't have to follow such rules. Yet it is often the same people hosting news channels then creating their own live programs online using their personal accounts. While they may be more conservative in their comments when they appear on mainstream media, they may take a much more sensationalist approach when they appear on their own personal channels. As far as audiences are concerned, the impression is all media is sensationalist and that not much progress has been made.

To get the full context on the Pai Hsiao-yen murder case, read our full piece: “The Killing Spree that Transformed Taiwanese Media.” And for more from Ming-Yeh Rawnsley, check out her insights from our earlier series of interviews on “How Taiwan's Media Covered Its Presidential Election.”

ORIGIN STORIES

China Yesterday, China Today

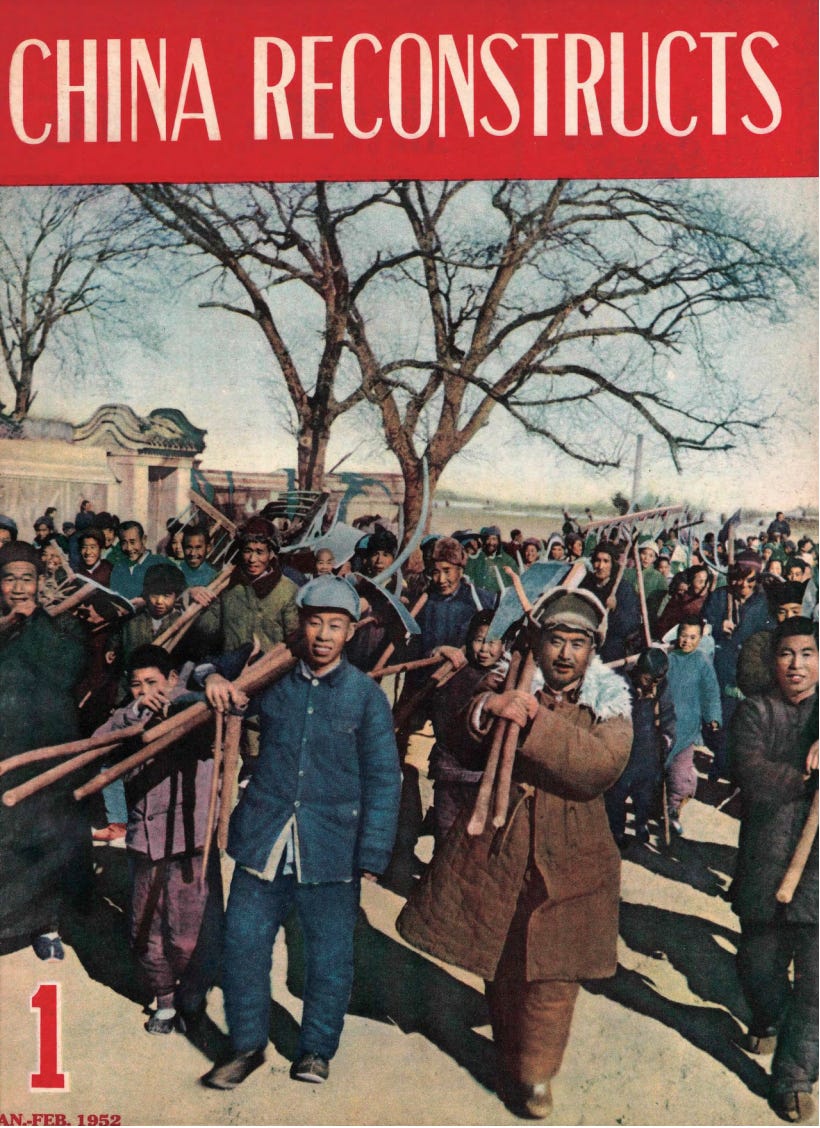

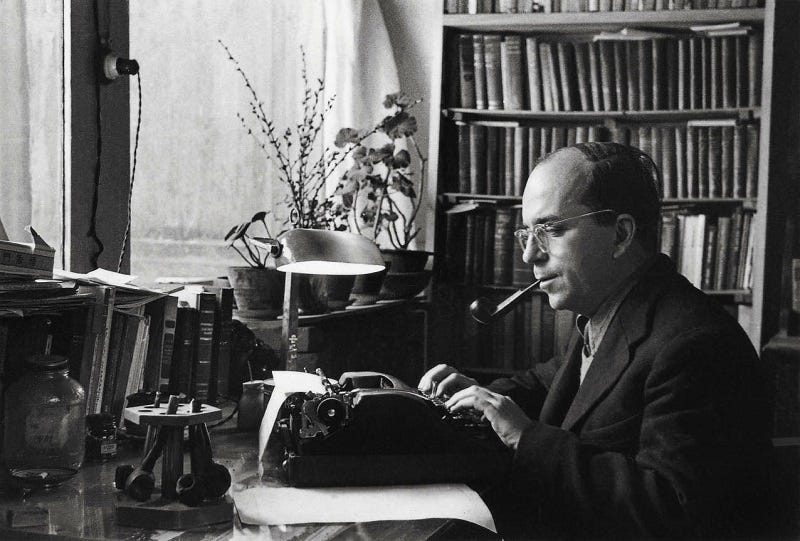

The magazine China Today (今日中国) is today a staple of China’s external communication apparatus — one point in a sprawling matrix of propaganda outlets run by the China International Communications Group (中国国际传播集团), or CICG, a foreign-language publishing and communications conglomerate directly under the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department. But the magazine’s origins go back more than seven decades to China Reconstructs (中国建设), a publication founded in 1951 by Soong Ch'ing-ling (宋庆龄), the third wife of Chinese “revolutionist” Sun Yat-sen, to “introduce China to the world and promote peace."

For help in launching the magazine, Soong sought out writer Jin Zhonghua (金仲华), who became publisher. She also invited Polish-born journalist Israel Epstein (伊斯雷爾·艾普斯坦) — pictured above — to return to China to take part in the venture. Epstein would stay on at the publication, in various positions, for more than 50 years, becoming a naturalized PRC citizen. China Reconstructs was renamed China Today (今日中国) in 1990.

Propaganda Redux

For Chinese media enthusiasts interested in a look back on the external propaganda of yesteryear — and up for an eye-popping realization of just how little the basic messaging has changed — check out this edition of China Reconstructs from 1954. The themes? China is a champion of peace; its economic path is unique and inspiring; the United States is a war-mongering source of chaos; the CCP is the champion of the developing world; and Western media are steeped in falsehood about China.

On the last count, Soong writes in her New Year's letter fronting the edition, in a line that might as well be from today’s edition of the Global Times: "The evil trickery of those who concoct the thick, black, scare headlines is failing."

CMP IN THE HEADLINES

Fade to Gray

Hong Kong is edging closer to the introduction of more national security legislation that many fear will further constrict press freedom and the city’s shrinking space for civil society and open dissent against the government. As Beijing’s point man on Hong Kong affairs, Xia Baolong (夏寶龍), traveled south to “inspect” the city, local authorities wrapped up a brief consultation period that they say delivered near-unanimous support for the law known as Article 23.

To discuss the possible implications for Hong Kong’s press corps, CMP Managing Editor Ryan Ho Kilpatrick recently sat down with Professor Francis Lee at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Journalism and Communication. Lee’s insights into how journalists have been adapting to the ever-widening gray area in what is and is not allowed under the city’s national security regime were featured in reports by Canada’s Globe and Mail newspaper and Politico online.

Find the full interview — “The Risky Business of Hong Kong Journalism” — on the CMP website.

Falling Tone

Until recently, Sixth Tone was one of the most interesting journalistic voices in China. Despite its state affiliation, the Shanghai-based outlet earned a reputation for human-centered, on-the-ground reporting that brought Chinese stories to international audiences in a way the country’s stilted state media couldn’t fathom — or stand, as it turns out.

In a series of interviews with past employees, The Wire China reveals how the publication has been neutered over the past year, with censorship ramped out, management demoted, and any semblance of critical reporting purged from the archives. Reporter Rachel Cheung also spoke to CMP’s David Bandurski about the fall of Sixth Tone — you can find his comments in the full article here (paywalled).

Pressing Back

On the eve of this week’s National People’s Congress, China announced that Premier Li Qiang would not hold the annual press conference that has concluded every session of the political event for more than two decades. “Pulling back on this practice for the first time in more than 20 years, at a time when there are a great deal of questions about the prospects for China’s economy, and plans in the government for addressing concerns, does not exactly inspire confidence,” David Bandurski told the Financial Times. Learn more in our “In the News” sections above.