How Taiwan's Media Covered Its Presidential Election

We ask six Taiwanese experts to appraise how the country's press corps handled coverage of its presidential and legislative elections in January.

Taiwanese democracy enjoys a stellar reputation around Asia and, increasingly, the entire world — where it is celebrated not just as a beacon of hope for Chinese-speaking communities but even as an example to follow for much older democracies now facing a resurgence in global authoritarianism.

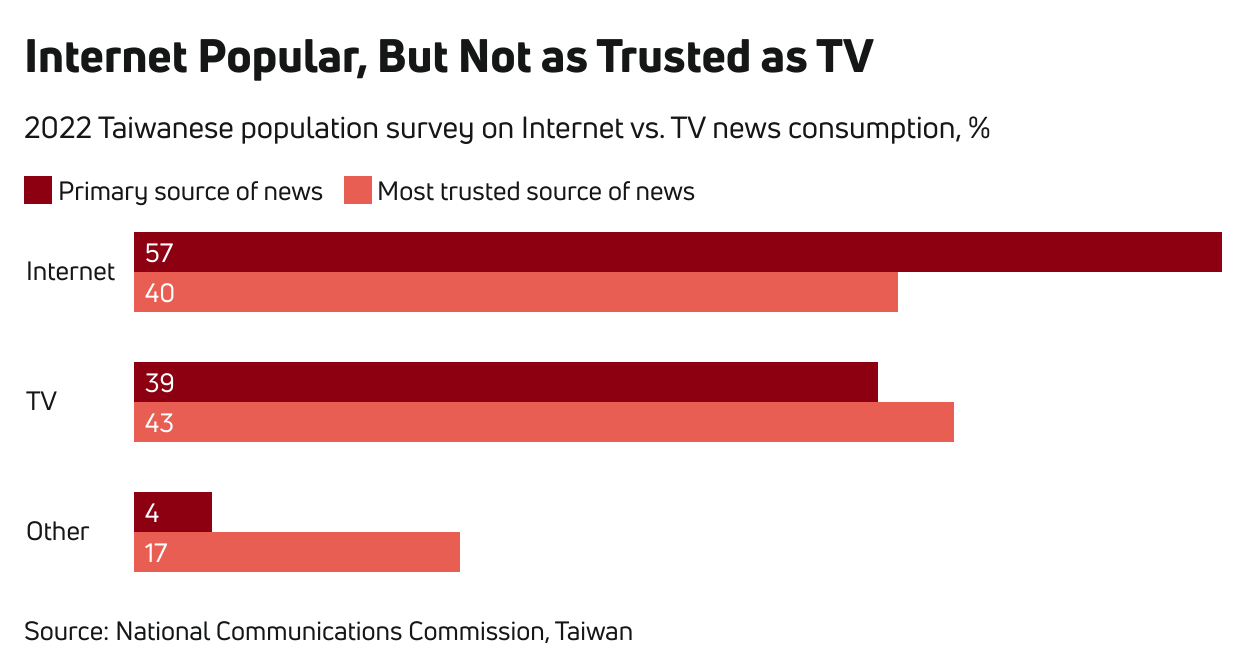

Taiwanese media, however, not so much. While the country excels in regional press freedom rankings, its mainstream news outlets are infamously sensationalist and partisan (barring very notable standouts like The Reporter, whose work we have spotlighted in our newsletter). The resultant cocktail is a uniquely Taiwanese one: high trust in democratic institutions and civil society, but low trust in the press.

So, as the world’s attention zeroed in on Taiwan for its national elections on January 13, how did its homegrown press corps measure up? To find out, we asked six Taiwanese experts in the field — journalists, fact-checkers, media scholars, activists — this question and more.

Jason Liu Chih Hsin (劉致昕)

Chih Hsin is an experienced, award-winning journalist who previously served as deputy editor-in-chief of The Reporter. He is the author of the book Making Truth: Inside the Global Fake News Industry (真相製造:從聖戰士媽媽、極權政府、網軍教練、境外勢力、打假部隊、內容農場主人到政府小編) and hosts the “I’m Sorry to Ask” (不好意思請問一下) podcast. His key points:

Information spaces are being fractured and fragmented based on ideological leanings.

The KOLs who dominate these spaces are increasingly being used to push propaganda and disinformation from across the Taiwan Strait.

Lingua Sinica: As a regular observer of disinformation efforts — and misinformation — what trends did you observe in Taiwan’s information space ahead of the recent election?

Liu Chih Hsin: In the run-up to the election, reality was broken up into fractured, fragmented, and ideologized information spaces. Many media conglomerates with divergent political leanings reported the news selectively and presented their own one-sided narratives. A lot of rumors that had appeared previously were recycled and systematically spread in the 2024 election — but this time around, many KOLs (網紅) and creators were involved, exploiting their fans’ trust to amplify rumors.

Reality was broken up into fractured, fragmented, and ideologized information spaces.

By analyzing the weekly rankings of pan-Blue (pro-KMT), pan-Green (pro-DPP), and uncategorized YouTube channels, we observed that YouTube viewership only became a major factor in the two weeks before the election. [TPP presidential candidate] Ko Wen-je was the undisputed king of YouTube — not only did he make it into the top 10 through his interviews and tweets, but his own programs also took three of the top 10 spots in the week before the election.

Among the YouTube channels of pan-Blue and pan-Green media outlets, emotional videos, clips of political programs, and videos with biased or completely wrong information became prolific in the four weeks before the election. In this election season, the pan-Green camp put forward [DPP politician] Wang Yi-chuan (王義川) as an opinion leader, with his commentary on YouTube receiving strong support from the pro-Green viewership.

The pan-Blue camp, meanwhile, was led by [KMT vice-presidential candidate and media personality] Jaw Shaw-kong (趙少康) and [2020 KMT presidential candidate] Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜), whose speeches and other videos got a lot of views. By contrast, if you look at policy debates and neutral, objective videos, only the presidential and vice-presidential candidates’ televised debates broke into the top 10.

LS: There has been a great deal of concern about disinformation stemming from China. How do you assess the threats from China ahead of and during the elections? How well did Taiwan perform in meeting these challenges? What more needs to be done, in your view?

Liu: Four weeks before the election, our team worked with IORG to monitor how Taiwan and the national elections were being reported on the social accounts of official PRC propaganda outlets. We found that China’s official propaganda system and Taiwan's pan-Blue media outlets and social media accounts were closely connected and collaborated frequently. Not only do they quote each other, but they even post together. Spokespeople from China’s Taiwan Affairs Office (TAO) have become important nodes and sources of many statements, rumors, and misrepresentations, influencing both Red (pro-PRC) and Blue media.

We found that China’s official propaganda system and Taiwan's pan-Blue media outlets and social media accounts were closely connected and collaborated frequently.

Taiwanese civil society and government have no means to influence China's information environment and news production — but, conversely, China's official propaganda system and social media platforms have become hotbeds and factories for the production of inaccurate statements on issues in Taiwan, and Taiwanese opinion leaders, celebrities, and scholars with ties to the PRC have become production line workers, receiving wages and participating in the production of this false or inaccurate information.

LS: What trends did you observe this time in how candidates interacted with the public and with the media? For example, were services like Threads and Instagram important sources of communication?

Liu: YouTube channels have become incredibly important, reaching various different groups and claiming top-of-mind awareness through the release of original content, live streaming, and collaboration with online celebrities. In this arena, Ko Wen-je outperformed all the other candidates. [DPP legislative candidate] Miao Poya’s (苗博雅) live streaming of her canvassing activities is another example, as is the KMT candidate's use of one-minute short videos in the same district as her. Social media is making candidates more personable and real, but it is also detracting from the most important parts of elections like collective dialogue and policy debates.

Ming-Yeh Rawnsley (蔡明燁)

Ming-Yeh is a Taiwanese media scholar, author, and journalist. She is a Research Associate at the Centre of Taiwan Studies at SOAS University of London, a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the University of Nottingham’s China Policy Institute, and a Research Associate at Academia Sinica. Her key points:

Balancing objective reporting and audiences’ preference for sensationalized content remains an enduring challenge for Taiwanese media.

Foreign media's focus on cross-strait relations limits their coverage of Taiwan.

Lingua Sinica: How do you think Taiwanese media performed in this election? What problems did you observe?

Ming-Yeh Rawnsley: Overall, I'd rate it 65 out of 100. Taiwan's media reflects the country's democratic values and has initiatives to combat misinformation. Repetitive news, sensationalism, and mismatched headlines are issues. While scholars advocate for positive reporting, audiences still prefer sensationalized content, creating a dilemma for the media. The National Communication Commission works to address these issues. Media have become more aware of boundaries, but there's a need for better newsroom practices. It's a balancing act between fulfilling audience demands and adhering to journalistic standards.

LS: Did you see efforts from Taiwanese media to target diaspora audiences?

Rawnsley: I haven't seen specific efforts from Taiwanese media to target the Chinese diaspora audience recently. The focus seems to remain on domestic voters. While there have been interactions with diaspora groups, they're not extensively covered in Taiwanese media. Taiwanese media often lack an international vision due to the constant cycle of elections and intense competition. Taiwan could facilitate the creation of platforms for interested individuals to engage with international communities effectively. For example, TaiwanPlus is a step in the right direction for international outreach. Additionally, empowering individuals to create their own content for specific communities could be a cost-effective and efficient way to increase Taiwan's international exposure.

Taiwanese media often lack an international vision due to the constant cycle of elections and intense competition.

LS: Would you say that foreign media often overlook Taiwan's intricacies due to their focus on cross-strait relations?

Rawnsley: While it's understandable for international media to prioritize certain angles, such as the China threat narrative and cross-strait relations, it's important to be aware of this framing and its implications. Similar framing occurs in UK coverage of US news. While it's understandable, diversifying perspectives could enhance coverage, revealing other important aspects of Taiwan like green tech development. This narrow framing, though common, becomes particularly apparent during elections, especially as Taiwan's democracy matures. For example, over 75 percent of Taiwanese voters don't buy into fear-mongering about potential conflict with China, indicating a shift in priorities. Continuing to frame Taiwan solely through the lens of cross-strait relations risks oversimplification and misinterpretation. It's essential for international media to explore diverse angles for a more nuanced understanding of Taiwan's political landscape.

Brian Hioe (丘琦欣)

Brian is a writer, activist, and one of the founding editors of the online magazine New Bloom, which covers politics, activism, and social issues in Taiwan and the Asia Pacific region. He is also a Non-Resident Fellow at the University of Nottingham's Taiwan Studies Programme. His main takeaways:

The TPP was the only party to capitalize on short-form video, earning a big Gen Z following.

International media was fixated on the presidential race and missed out on interesting stories in legislative polls.

Lingua Sinica: Overall, how do you think Taiwanese media performed in the recent elections? What problems did you see?

Brian Hioe: On the whole, Taiwanese media continued to behave in a partisan manner during the elections. Pan-Blue media primarily reported on the KMT and TPP in a favorable light, while pan-Green media reported on the DPP positively. Both sides aimed to amplify scandals faced by the other side. However, this did not escape the focus on partisan mudslinging that characterizes news coverage in Taiwan, in this way failing to hold politicians to account for their statements. This is not a problem unique to this election cycle.

LS: What new types of media have we seen play a decisive role in the recent elections? We’re hearing about short-form video, for example.

Hioe: The short-form video, as in the TikTok Reel or Instagram Story, has been a particular matter of focus because of its popularity among young people. Some attribute TPP presidential candidate Ko Wen-je’s popularity among Gen Zs, for example, to his successful use of TikTok, which other candidates and parties failed to capitalize on.

At the same time, while social media-based types of media such as short-form video play a key role, much of the political discourse during election cycles continues to be guided by television shows — often political talk shows but also television dramas such as Wave Makers. When the race was a four-way one between the KMT, DPP, TPP, and Terry Gou as an independent, one notes that Gou’s vice presidential candidate, Tammy Lai, played the DPP-like presidential candidate in Wave Makers. Likewise, KMT vice presidential candidate Jaw Shaw-kong is a media personality known for his mastery of the political talk show.

Some attribute Ko Wen-je’s popularity among Gen Zs to his successful use of TikTok, which other candidates and parties failed to capitalize on.

LS: What angles on Taiwan’s elections do you think foreign media omitted in their coverage?

Hioe: I think there was a comparative lack of focus on local races and highly local issues. To be sure, international media has its priorities, and so is more likely to focus on the presidential race and the overall outlook for the legislature as a whole. However, there were a number of perspectives that were neglected in terms of, for example, how and why KMT political dynasties returned to power after several years in which they had been pushed out of established seats. It tended to be these kinds of stories, requiring a great deal of context, that were omitted in international coverage.

LS: What differences did you see in how the different political parties used media or social media?

Hioe: The TPP and DPP, as parties with younger bases, tended to be more adept at the use of social media than the KMT. By contrast, the KMT has failed to embrace social media in and of itself, and often uses it for the visual advertising that is already prevalently found as a part of streetside campaigning. The DPP mostly recapped some of its past hits, including election ads that riffed on previous ads. The TPP was not particularly innovative either, but its engagement on TikTok may serve to drive up its popularity among young people. The DPP has, however, chosen not to engage with TikTok with the view that it would be giving the Chinese platform legitimacy if it did.

Kwang-yin Liu (劉光瑩)

Kwang-yin is the Managing Editor of CommonWealth Magazine (天下雜誌群), a monthly current-affairs publication in Taiwan, and the host of their Taiwanology podcast. Her primary points:

Uncertainty in this election meant there was even less serious policy discussion than usual.

Old-fashioned bulletin board systems could be an underestimated factor.

Lingua Sinica: How did Taiwanese media coverage of this election differ from that of the previous presidential election in 2020?

Kwang-yin Liu: In the past, it was customary for TV stations to inflate the numbers of votes in their polling day coverage to make them look more dramatic, since the Central Election Committee’s numbers tend to come in more slowly. This was heavily criticized as symptomatic of Taiwanese media’s sensational and unprofessional behavior. I think they did much better this time, and weren’t inflating those numbers as much as before.

I should also say that this campaign was particularly weird to cover. Up until about one month before polling day, we were still not sure how many candidates were going to be on the ticket. In previous elections, we’d already have a pretty good idea of who's going to run months ahead of time, so we could focus on them and go into the details of their policy platforms. But this time I feel like a lot of the airtime was sucked out from serious discussions. In this campaign, personal attacks got more attention than before, which could be attributed to the very limited campaign time after the confirmation of the three candidates. I think they felt they had to use this limited time to deal the most powerful blow possible to their opponent, and media were forced to follow these irrelevant leads, making it impossible to follow up on crucial issues.

Up until about one month before polling day, we were still not sure how many candidates were going to be on the ticket… a lot of the airtime was sucked out from serious discussions.

LS: Do you think there was anything that could have been improved in the way Taiwanese media covered these elections?

Liu: The German scholar Gunther Schubert published an article on our platform dealing with why there is so little policy debate in Taiwan’s election. I have to agree with him — people don’t seem to care about policies anymore. I guess Taiwan is not a rare case in this regard. But I do think that, in a perfect world, the media would cover policies more than trivial wrongdoings, and be less influenced by what does well in terms of clicks.

LS: Did you notice any particular media that was the most successful in reaching ordinary people in this cycle?

Liu: Ko Wen-je was shut out from mainstream media so YouTube and TikTok became crucial for his campaign. His live streams on YouTube and goofy dancing videos were extremely popular because that's how young voters consume media. They might not have a TV but everybody has YouTube on their phone. I don’t know if this made an impact on his voting numbers, but for young people who felt that none of the KMT or DPP candidates spoke their language, [they might think that] Ko gets us.

Ko Wen-je was shut out from mainstream media so YouTube and TikTok became crucial for his campaign.

Something that nobody has really talked about is BBS [Bulletin Board System]. Think of it as the Reddit of Taiwan, but from the analog era. It was highly popular when I was a college student. My colleagues told me a lot of Ko’s supporters spent time on BBS sites sharing gossip and reading the news. Many were engineers working in high-tech workplaces where smartphones are not allowed, so things like TikTok are meaningless to them.

The conundrum of legacy parties is that TikTok is an effective way of reaching young voters, but is Chinese. There are some people who say the DPP did not perform well with younger voters because they don't use TikTok. I'm not sure that's the main reason. I think it’s natural for them to think the DPP has been around for a long time yet their lives haven't improved, so they want to support a maverick candidate like Ko who is going to “drain the swamp.”

Austin Wang Horng-En (王宏恩)

Austin is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where he has been investigating Chinese disinformation campaigns on YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok during the Taiwanese election. His main points:

As China’s economy flounders, it’s shifting focus from pro-PRC to anti-US narratives.

Taiwan’s bitter partisan divides are being exploited to push propaganda.

Lingua Sinica: What struck you as significant about the methods of spreading disinformation during this election, and the content of this disinformation?

Austin Wang: Between 2020 and 2024, China's strategy became more long-term and more mature. They’ve spent years running Facebook groups about Taiwan politics and referendum campaigns, and it’s possible they could also be using coordinated behavior to influence the algorithm on social media [to make their messages spread further]. Four years ago, they at most used a lot of bots to spread misinformation.

LS: What has changed about Chinese tactics since the last election cycle?

Wang: Four years ago, misinformation mainly focused on promoting a positive image of China and the benefits of China-Taiwan cooperation, along with a few attacks on the DPP. This time, however, China also knows that its economy is in trouble, so the main theme is to defame the United States, trying to persuade Taiwanese people the US is not trustworthy.

China knows that its economy is in trouble, so the main theme is to defame the United States.

LS: Did this have any impact on the elections?

Wang: Its impact on the election is indirect. The overflow of information services makes different partisans rely on different sources of information. As a result, voters became highly polarized. It explains why no one chose to do strategic voting in the presidential election: even though KMT and TPP supporters had recognized their preferred candidate had no chance of winning, they simply hated the other options so much that they refused to switch their vote choice.

And this polarization continued after the election. The supporters of the three major parties still attack and accuse each other, so there is no sign of cross-party cooperation even though no party reached a majority in the Legislative Yuan. This internal crisis, however, perfectly fits [former PRC leader] Mao Zedong's strategy with the United Front: divide [the enemy], ally with the weaker group to defeat the stronger group, and repeat this process until everyone is on your side.

Hui-An Ho (何蕙安)

Hui-An is the head of international projects at Taiwan FactCheck Center (TFC). She also covers news in the fact-checking world, from the latest research on misinformation to the effectiveness of fact-checking and media literacy intervention. Her main points:

Misinformation in Taiwan is proliferating and becoming more sophisticated and untraceable, especially on platforms like TikTok.

Social media accounts spread claims of electoral fraud, mostly based on minor and quickly corrected procedural mistakes rather than anything widespread.

Lingua Sinica: Has the amount of fake news shared in this election significantly increased in comparison to previous election years?

Hui-An Ho: Unfortunately, we don't have specific data; but the overall sense is that the volume of misinformation is continuously growing. With newer social media platforms like TikTok gaining popularity in Taiwan, we are also observing misinformation originate on TikTok and then spread to other platforms, which marks a change from previous years.

LS: When it comes to information warfare, how have PRC tactics changed over the years?

Ho: In general, we perceive that China's techniques and strategies in spreading disinformation have become more sophisticated and covert over the years, making it more challenging for us to ascertain whether a piece of misinformation originates from China. Therefore, even though many inquire if mis-/disinformation from China is on the rise, it's difficult for a small fact-checking organization like ours to provide a definitive answer. Collaborations with more research teams are needed to understand this issue better.

LS: Could you give us your post-election assessment of how things went? Do you think disinformation played an important role?

Ho: This year's post-election situation was notably different from previous years, with many videos on social media making claims of electoral fraud. These videos mostly captured procedural mistakes by election staff rather than widespread fraud. Upon investigation, it was found that these mistakes were promptly corrected on-site by public observers or election monitors.

This year's post-election situation was notably different from previous years, with many videos on social media making claims of electoral fraud.

Another unique aspect of this election was the role of influential social media influencers in propagating these fraud narratives. Before the election, a political influencer released videos questioning the election’s integrity, garnering millions of views. Post-election, some influencers further amplified videos claiming vote rigging, leading to extensive exposure and media coverage.

Our observations indicate that disinformation campaigns from China are becoming more covert and sophisticated. There seems to be a strategy to avoid overt foreign interference, which might backfire by alienating Taiwanese voters. The disinformation narratives before the election primarily targeted the ruling party and its candidates, focusing on government incompetence or moral flaws of candidates. However, it’s challenging to distinguish whether these actions stemmed from foreign influence or local sources, like opposition supporters. Taiwanese research teams such as DoubleThink Labs and Taiwan AI Labs have released reports analyzing foreign disinformation activities.

LS: What differences did you see in how the three parties used media or social media?

Ho: All political parties have increasingly turned to social media, especially to appeal to younger voters, with strategies like online interviews and live streaming. Candidates with limited funds in particular have sought to amplify their reach through collaborations with social media influencers, such as interviews with influencers or “a day with the candidate.” An interesting observation was the heightened activity of supporters for a particular candidate on the TikTok platform, where the number of supportive videos for this candidate was significantly higher for them than for others. This trend could be linked to the candidate's larger base of young supporters.

Loved this. Thank you.