The Killing Spree that Transformed Taiwanese Media

How a set of tragic kidnappings and murders in the 1990s exposed Taiwanese media's problems — and how some of these problems are still with us today.

Today, Taiwanese media operate under a strict set of decency regulations. Alcoholic drinks, cigarettes, and betel nut all need to be blurred on-screen. So, too, must even minor acts of violence. During my stint working for Taiwanese TV, I was obliged to blur screenfuls of footage from the Hong Kong protests — because viewers had to be protected from the sight of pushing crowds.

But things weren’t always this way. Contemporary squeamishness, as patronizing as it can sometimes seem, is inarguably an improvement on the chaos that used to reign in Taiwanese media. The tipping point for the industry came in 1997, when press coverage of a tragic kidnapping and murder case endangered lives, outraged the nation, sparked an international incident, and precipitated a slew of new rules.

This was the Pai Hsiao-yen Murder Case (白曉燕命案). Sixteen-year-old Hsiao-yen, the daughter of Taiwanese TV host and actress Pai Bing-bing (白冰冰) and Japanese author Ikki Kajiwara, was abducted on her way to school in New Taipei’s sleepy, suburban Linkou District in April that year. Her kidnappers demanded an astronomical ransom from her mother and threatened to kill Hsiao-yen if the police were involved — a risk that Bing-bing ultimately decided she had to take.

Police requested a 12-day information blackout for the media, but within hours Hsiao-yen’s kidnapping had already become front-page news in two of the nation’s biggest papers: The Great News Daily (大成報) and China Times (中國時報). Neither was willing to get scooped and decided their professional rivalry mattered more than Hsiao-yen’s life. Authorities spent a small fortune trying to buy every copy of the papers but the news was already out, and other outlets soon followed their lead.

When Bing-bing set out to deliver the ransom days later, tailed by undercover detectives, they were pursued by not just a motorcade of reporters but even a news chopper. The hostage exchange, unsurprisingly, did not go through. The same dynamic played out again and again as clandestine handovers with the kidnappers were foiled by obsessive media coverage.

At the end of the month, Hsiao-yen’s remains were discovered. She had been horrifically abused and killed by her kidnappers after the second exchange with Bing-bing was aborted due to media attention. Shockingly, images of her naked corpse were printed on the front page of the China Times.

Baying for Blood

The nationwide manhunt that ensued saw five more slayings by the trio of kidnappers in the months before they were caught. When one of them was killed in a shootout with police, the United Daily News (聯合報) and China Times carried graphic images of his body on their front pages. In a final, desperate bid for bargaining power, the last of the suspects broke into the home of South Africa’s military attache in Taipei and took his family hostage. Reporters who rushed to the scene monopolized his attention, conducting live, on-the-air interviews while negotiators struggled to get a word in edgeways. When the military attache’s wounded wife and daughter were released, he had to plead with the media scrum to let emergency services reach them.

By the time the whole ordeal came to an end, many viewers were fed up. They condemned the “eight black-hearted media outlets” (八大黑心媒體) who were widely seen as responsible for Hsiao-yen’s death: The Great News, China Times, China Daily (中華日報), Min Sheng Daily (民生報), The Independence Morning News (自立早報), First Hand Report (第一手報導), TVBS, and Rebar News (力霸友聯電視台). Several would not survive to the present day, although two — TVBS and China Times — are still huge players in the Taiwanese media landscape.

Media industry bodies took the initiative, issuing new guidelines and conventions for reporting on kidnappings and other crises in quick succession through the late 1990s and early 2000s. Public broadcasters like the Public Television Service, or PTS (公視), founded in 1998, led the charge in imposing new discipline measures that would raise the bar for Taiwanese media.

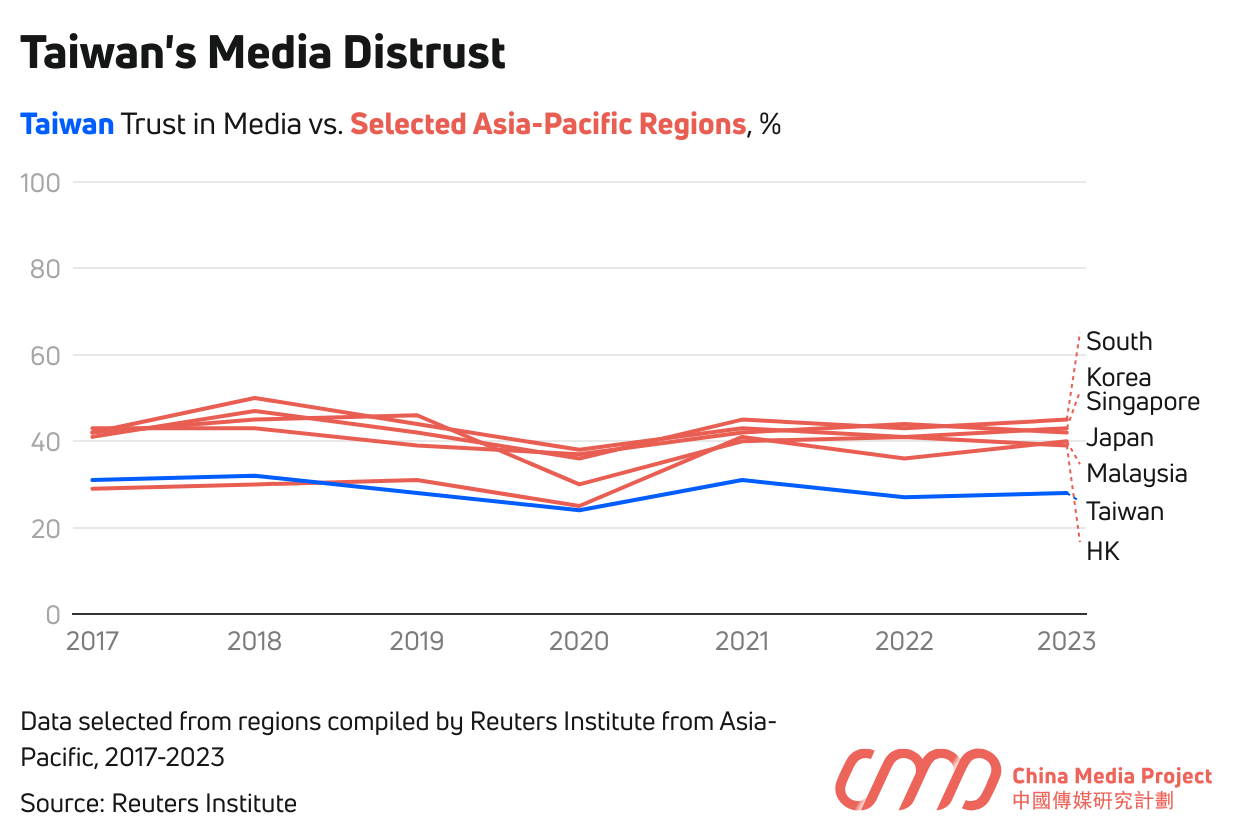

And yet, there is still a contradiction at the heart of Taiwanese media. Thanks to efforts like these, PTS is today far more trusted than its commercial competitors — but far less viewed. When the public outrage around the Pai Hsiao-yen case cooled, news consumers reverted to their bad old ways, rewarding the most sensationalist coverage with their time and money.

“Media today are still chasing gossip that run roughshod over human dignity,” a reader wrote to the Liberty Times (自由時報) in 2005, calling the Pai Hsiao-yen case “a tragic example of the bitter consequences of abusing Taiwan’s press freedom.”

Since then, however, Taiwanese media have faced other tests and faired better — however low the bar may have been. During the 2013 kidnapping of a Taiwanese tourist in Malaysia and the abduction of a Hong Kong businessman in Taiwan two years later, for example, Taiwanese media behaved with “self-discipline,” according to Shi Hsin University (世新大學) media scholar John Wen (温偉群). “Most media outlets cooperated in refraining from releasing unauthorized information” in these instances, he wrote on the twentieth anniversary of the Pai Hsiao-yen case.

Today, Taiwan’s media remains something of a paradox: a shining example of press freedom, yet a cautionary tale of how that freedom can be abused; a web of tight and often constrictive regulations, but one which still struggles to reign in news outlets only too happy to provide salacious content to the consumers who demand it.

For more on the issues facing the industry, check out our recent series of interviews with Taiwanese experts about how the country’s press corps covered its recent national elections. In a piece for Lingua Sinica last November, Taiwanese journalist and fixer Xin-yun Wu also used her own experience to explore some of the ways mainstream Taiwanese media is hamstrung by a highly saturated and competitive media environment that continues to produce sensationalist clickbait journalism.