Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 8 Feb

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

Today’s newsletter, like newsletters past, takes you on another whip around some of the key issues occupying Chinese-language media around the world — from Beijing’s forceful campaign to keep spirits high as stocks plummet and savings are lost in China, to a new venture to invigorate Chinese-language journalism born from far-flung exile and diaspora communities.

This time, we look with a sharper focus at Hong Kong, where journalists who have barely come to terms with the new normal under the 2020 national security law are now faced with a whole new set of legal threats in the form of Article 23, a homegrown security law that could be even more far-reaching than the NSL. We look below at how provisions around “state secrets” could threaten journalism, though we also note that this is just one facet of the risk possibly facing media. Recently, the territory’s secretary for justice warned that media could be charged with “abetting” wanted activists merely by quoting them.

To end on a less somber note, we’d like to wish all our readers a very happy Lunar New Year from the Lingua Sinica (and China Media Project) team. Finally, commiserations to my fellow dragons about to confront our 本命年, meaning that we are starting new 12-year zodiac cycles — which according to some means that we must proceed with care.

See you again in the Year of the Dragon!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

TRACKING CONTROL

Using the Press to Pacify Hong Kong

The public consultation period for Hong Kong’s homegrown national security law — known locally as Article 23 — began at the start of this month. Members of the public were given until February 28 to express their views on the proposed legislation, two months less than they received when the law was last floated, then sunk by mass protests, in 2002.

On the morning of February 5, even before the public had an opportunity to air opinions for or against, China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency came out guns ablaze to frighten everyone into submission. The editorial, “Why Are Anti-China Agents of Chaos So Afraid of Article 23?” (為什麼反中亂港分子如此害怕和阻撓23條立法), was written under a penname that translated “Hong Kong and Macau Pacified” (港澳平), and it grew more and more colorful as it warmed to its theme: opposition means seditiously siding with the West.

Critics of the proposed legislation are, in order: “ants on a hot pan,” “evil forces,” “flies and dogs,” and “thieves with a guilty conscience” who have been “getting away with monstrous crimes,” “refuse to be proper Chinese,” and are “happy to be dogs” for their “Western masters.” In short, if you oppose the law, you must be hiding something.

In an apparently coordinated manner, the editorial was rapidly reprinted and endorsed by the Central Government’s Liaison Office and every major pro-Beijing media outlet in the city. The wall-to-wall coverage made it clear that this was the official line.

“I’m so scared”

Back in 2002, the government received over 90,000 responses from the public during its Article 23 consultation. But who, you might be wondering, would dare to speak out in today’s pervasive atmosphere of fear and suspicion? The answer, at least according to this report from Sunday by TVB, is “no one.”

The pro-establishment station, a safe space for government supporters mockingly referred to as “CCTVB” after the Chinese state broadcaster, attempted to interview dozens of people on the street about Article 23 but not one would respond.

In a grim testament to how far Hong Kong’s freedoms have withered under the national security law — even without the additional pressure of local security legislation — one woman pleads with the reporter to ask someone else.

“Saying one wrong thing could put me in danger,” she says. “I’m so scared.”

REDLINES

Putting Stock in Positivity

As online censors sought to expunge negativity on the economy, creating a public opinion atmosphere infused with what the CCP since 2013 has called “positive energy” (正能量), the official party-state media continued with a march of everything-is-just-fine propaganda.

On Tuesday, the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper ran a commentary on page five attributed to Tang Ting (唐婷), identified as the office operations manager at China Construction Bank, one of the country’s “big four.” Tang spoke less like a financial professional and more like a political functionary. “Finance is an important part of a country's core competitiveness,” she began, before cleaving off into official-speak that signaled obedience over real confidence. “On the new journey, by adhering to the directions of Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, comprehensively enhancing financial work skills, and acting as the main force to serve the real economy, we will surely be able to contribute more strength to the construction of a strong country and the revival of the nation.”

The Ghost of Propaganda Past

But amid the stock market volatility in China, the overweening positivity of the CCP’s official media has not gone unnoticed by internet users — underscoring the blunt edge of sharp over-confidence.

Late last week, People's Daily Online removed an article dating back to 2016 after it became a fresh source of ridicule on Weibo amid continued economic and financial pain. The article, written by Zheng Bingwen (郑秉文), an economist at the official Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), predicted that China would join the ranks of "high-income" countries by this year, 2024.

Before its deletion, the article was archived by China Digital Times. “Just look at this pie, getting bigger and bigger,” one Weibo user commented wryly last week before the deletion. “The good days are behind us, that’s for sure,” said another.

HOT SEAT

“Senator, I’m Singaporean.”

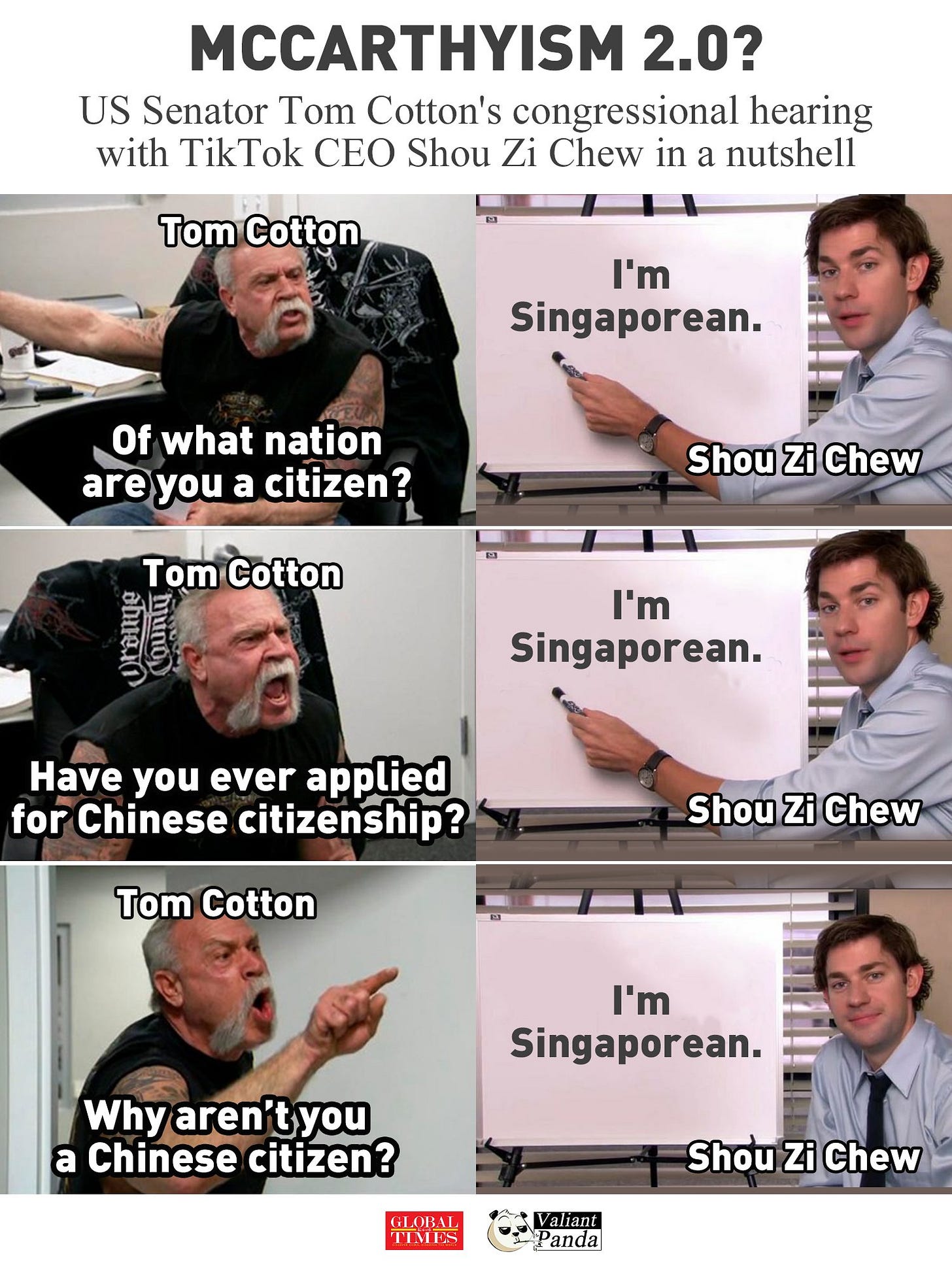

In a heated hearing in Washington, DC, last week, Shou Zi Chew (周受資), the CEO of the short-form video hosting service TikTok, faced tough questions about his nationality from members of the US Senate. The purpose of the hearing, which was attended by five tech CEOS, was to address the impact of social media on children — and to hold companies to account for addressing real problems. But as Senator Tom Cotton of Arkansas leaned into the microphone with his questions, the room grew especially tense.

“Of what nation are you a citizen?” Cotton asked Shou.

“Singapore, sir.”

“Are you a citizen of any other nation?”

“No, Senator.”

“Have you ever applied for Chinese citizenship?”

“Senator, I’ve served my nation in Singapore . . . “

“I asked . . . . “

“No, I did not.” . . . .

“Have you ever been a member of the Chinese Communist Party.”

“Senator, I’m Singaporean. No.”

Snippets from the hearing quickly went viral on social media platforms, including TikTok. Senator Cotton’s persistent questioning of Shou’s nationality — a treatment none of the other CEOs were subjected to — and his seeming suggestion that Shou’s ethnicity should raise questions about his political affiliations, prompted anger from ethnic Chinese in Singapore. One Singaporean remarked online that the senator’s questions showed “pure ignorance.”

Fodder for Viral Propaganda

The dramatic nature of the exchange between Cotton and Shou made this short section of the hearing perfect fodder for Chinese state media, which quickly seized on the moment as an illustration of American ignorance and the supposed irrationality of its curtailment of TikTok’s global ambitions — which in recent months has been an oft-repeated criticism from state media.

The Global Times, an outlet under the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily, characterized the treatment of the CEO as a "witch-hunt" aimed at vilifying China and the enormous success of its indigenous tech firms. The outlet quoted one analyst as saying that "the repeated US acts showed the US oppression of companies with a Chinese background."

CGTN, the global broadcasting arm of the state television network China Central Television (CCTV), responded with a social media poll asking readers a series of questions skewed clearly toward a negative reading of not just Cotton’s actions but those of the United States, and supporting the idea that US legislators are motivated primarily by prejudice toward China. Before asking readers to respond with “agree” or “disagree,” the poll posed a question that read like an opinion statement: “Some senators have been criticized for frequently inciting panic over China-related issues, demonstrating their ignorance, arrogance and prejudice against China, which is not conducive to the healthy and stable development of China-U.S. relations.”

In a post on February 1, Valiant Panda, an account on X (Twitter) affiliated with the Global Times, branded the hearing “McCarthyism 2.0" — a reference to the "Red Scare" led by US Senator Joseph McCarthy in the late 1940s and 1950s. The post included a graphic card that opposed images of an enraged Paul Teutul (the star of the reality show “American Chopper”) as Cotton, and American actor John Krasinski as a calm Shou.

FLASHPOINTS

When Journalism is a State Secret

For journalists in Hong Kong, one of the most concerning elements of Article 23 (See “Redlines”) security legislation due to come into force within the next year is new provisions around the theft of “state secrets” (竊取國家秘密) — the language of which appears to be lifted straight from related laws in mainland China.

Much like with the national security law imposed by Beijing in 2022, local authorities are quick to dismiss these concerns by reminding the public that many nations around the world — including some of the most democratic and liberal ones — have laws targeting similar crimes. On the surface, this seems like a fair point. But the devil is in the details. While many jurisdictions have laws surrounding national security, espionage, and treason on the books, China’s stand out for their arbitrary nature, the opacity of legal proceedings, and the heavy sentences they carry.

Last year, for instance, French journalists were detained by their country’s domestic intelligence agency for using confidential documents to expose French forces' complicity in a campaign of arbitrary killings in Egypt. Two journalists in Finland — ranked fifth in the World Press Freedom Index — were also found guilty of revealing state secrets. Both cases caused an uproar in their respective countries, sounding alarm bells in civil society and among peers in the press. But consider how their cases played out in comparison to those of PRC journalists convicted of the same.

In the case of the Finnish journalists, their conviction only carried no jail time — just a fine for the lead reporter. Conversely, when Chinese journalist Gao Yu (高瑜) was convicted of leaking state secrets after she sent foreign journalists a copy of “Document 9” — an internal CCP briefing heralding Xi Jinping’s crackdown on the press and civil society — she was sentenced to seven years in prison.

The Fog of National Security

More recently, Australian newscaster Cheng Lei was detained for three years on charges of sharing confidential documents. When she was finally released last year, it came to light that the “confidential document” in question was merely a press release shared slightly before embargo. Then, this week, writer and fellow Australian Yang Hengjun received a suspended death sentence for national security-related charges that are still shrouded in mystery. And these are just the most high-profile cases. Little is still known about the detention of Chinese journalist Haze Fan, released in 2022 “pending trial” for national security offenses.

The precedent set by ongoing national security law trials in Hong Kong is not promising, either. In the closely-watched case of the 47 pro-democracy politicians on trial for holding unofficial primaries (see “Spotlight”), defendants have already been held in pre-trial detention for years and face potential life sentences if convicted — in trials where the city’s usual legal protections do not apply. Hong Kong’s security secretary says the government will “consider” a public clause exempting journalists and others from prosecution if the information disclosed was in the public interest, as lawmakers and legal bodies have been urging.

For now, whether that finds its way into the final text and what exactly it will look like remains, like so much else, shrouded in mystery.

SPOTLIGHT

Bearing Witness

For many, live news blogs might seem an outdated format in 2023, a relic of an earlier, simpler time when news junkies camped out at their desktop computers to eagerly refresh a web page on their favorite site. But the news blog of The Witness (法庭線), an independent outlet launched in Hong Kong in 2022 to monitor court developments in the city, is proving that this old format can have new life.

The site’s news blog dedicated to the national security trial of Apple Daily owner Jimmy Lai has been a must-read source of reporting on breaking information.

The landmark trial — one expected to set the tenor for media freedoms in the city for years to come — has been three years in the making and is expected to last 80 days. At a time when Hong Kong’s once-vaunted legal system is becoming increasingly opaque and politicized, The Witness’s reporting puts readers in the courtroom, allowing them to, if nothing else, at least bear witness to the seismic, uncontrollable shifts shaking their home.

History’s First Draft

If there’s one trial even bigger than Jimmy Lai’s, it’s that of the “Hong Kong 47” — a slew of opposition figures charged with national security offenses due to an unofficial primary they participated in to pick the best pro-democracy candidates ahead of legislative elections that were subsequently canceled. Like Lai, the defendants have all been jailed for years before even being convicted.

The old cliche that journalism is “the first draft of history” is usually too overused to evoke much, but Initium Media’s (端媒體) immersive, exhaustive, and visually captivating reporting on the trial — “Hong Kong’s Biggest National Security Case” — is the kind of work it was created to describe.

Through court drawings, infographics, and a catalog of testimonies, the Hong Kong-born, Singapore-based outlet has created something invaluable both to readers today and in the future, as they try to make sense of this overwhelming and often tragic period in Hong Kong’s history.

ANTI-SOCIAL LIST

Wailing Walls on Weibo

Last week the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets careened downhill, with drops of more than 6 and 8 percent respectively by Friday. The slide continued this week, as drops of around 10 percent hit more than 1,800 stocks — accounting for 30 percent of all stocks listed in China.

As the declines, which stemmed from poor economic sentiment, hit pocketbooks and personal investments, state censors and commercial internet platforms sought to temper negative sentiment online. In response, many Chinese flocked to the official Weibo account of the US Embassy in Beijing, where they felt their comments might survive long enough to be seen.

Anger and frustration gathered on posts by the US Embassy on completely unrelated topics — such as the use of cutting-edge science to save giraffes in Namibia. “Please, US government, save Chinese stock investors,” read one comment on the post. Censorship soon kicked in, however. “Why can’t I ‘like’ this post,” one user in Guangdong province asked over the weekend.

The next day, a user from Hebei visited a comment section under the giraffe-related post, which had grown much quieter. “Let me just see if I can include the word ‘stock’ here, and whether it will be removed.”

By Monday evening, it seemed that one of the tactics on social media was to put the blame for stock market volatility squarely on securities firms. One of the top results for searches on Weibo for “stocks” (股票) was a post from the account of the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily about a stern notice from the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC), which warned that “in the midst of recent continuous fluctuations in the stock market, some unscrupulous elements have engaged in illegal profit-making, damaging the legitimate rights and interests of investors.” It was unclear what the CSRC meant by its broad accusations of “market manipulation and malicious shorting.”

Voices of Desperation

Despite censorship on Weibo, posts on Tuesday continued to share news of personal disaster at the hands of a troubled market — and perhaps foolish investment choices. “Folks, I am a stock market victim,” one lengthy post began. “I took out an online loan of 800,000 plus my own salary to the tune of 300,000 — for a total loss of more than 850,000, resulting in 1.3 million dollars in debt. This is all my fault, I did it to myself. I've been reduced to a crazy stupid loser gambler.”

A comment under the post said: “This type of person is everywhere, people imagining they were investing when in fact they were gambling. And they borrowed other’s money to gamble.”

REACTIONS

Too Close for Comfort

Last week, China’s top civil aviation authority announced unilaterally that it would now disregard arrangements reached with Taiwan in 2015 to ensure that north and south-bound commercial flights by Chinese airlines remain a safe distance from the so-called “median line” — a middle line through the Taiwan Strait meant to dissuade aggressive actions from either air force. The line of demarcation was tacitly agreed by China and Taiwan after it was defined in 1955 by US Air Force General Benjamin O. Davis Jr.

Under the “offset measures” of the 2015 arrangement, flights along the north-south commercial flight path known as M503 were moved a further 11 kilometers to the west, in the direction of China’s coast, which meant they maintained a safe distance from the contentious median line, sometimes also called the “Davis Line.” But the announcement on January 30 by the Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC) suddenly dropped the arrangement, meaning flights could now pass as close as 4.2 nautical miles from the media line.

The sudden change, an apparent ratcheting up of pressure from China, prompted an immediate response from Taiwan’s government, and a wave of concerned reports from the Taiwanese press.

In Taiwan, Context and Discussion

In a news report on China’s actions, Radio Taiwan International, a government-owned broadcast and news platform, emphasized the “unilateral” nature of the decision. The rest of the report focused on the remarks of Chen Binhua (陳斌華), a spokesman for the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council, who addressed the M503 issue during a press conference the day after the CAAC announcement, stressing China’s claims of sovereignty over Taiwan. Chen refused to respond to a question, RTI noted, about whether the CAAC decision was linked to recent elections in Taiwan.

The Central News Agency (CNA), a semi-official Taiwanese wire service operated independently as a non-profit, put the M503 row in full context with a timeline of related points and events going back to the 2015 agreement. The article quoted Shen Ming-Shih (沈明室), a researcher at Taiwan's Institute for National Defense and Security Research, as saying China’s actions were meant to “break the symbolism of the strait’s meridian line,” and to “increase pressure on Taiwan’s air defense monitoring.”

In a more recent piece of related analysis, Taiwan’s Storm Media (風傳媒), an online outlet founded in 2014, offered a more colorful assessment, characterizing the objections of the Taiwan government as “ineffective”:

Now Taiwan is accusing the mainland of being ‘one-sided,' which is literally true, but such an accusation is ineffective. It's like when lovers break up, the one who is dumped calls the other ‘one-sided’ just to spite him to his face. But what use is it really calling him ‘one-sided’?

In China, Straight-Faced Talk of Sovereignty and Safety

As media in China reported on the M503 story, any pique on Taiwan’s part was irrelevant overreaction given claims to Chinese sovereignty. Reports from outlets like the official China News Service relied almost entirely on the Chen Binhua press conference, at which he argued that “Taiwan is an inalienable part of China, and this so-called 'straits meridian line' does not exist." The state-run China Daily maintained the fiction that the change had been made only to "ensure aviation safety and convenience for both sides of the Taiwan Strait."

One outlet that dismissed the Taiwanese reaction as mere “anxiety” was Zhinews (直新聞), a media brand created in Guangdong under the Shenzhen International Communication Center (SICC), a new office under the city’s propaganda department tasked with external propaganda toward Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan. ICCs like Shenzhen’s are part of a new CCP strategy for external propaganda that we have reported in some detail at the China Media Project. Seeming to answer the question Chen Binhua would not about links between the M503 decision and the recent Taiwan elections, the Zhinews article suggested Taiwan’s electorate should have known that the election as president of DPP candidate Lai Ching-te (賴清德) “would close the door on any prospects of dialogue between the two sides.”

NEWSPEAK

The Region Formally Known as Tibet

Sixth Tone is the latest publication to board the “Xizang” train, publishing a piece in late January about cloned “Xizang cattle” on the “Qinghai-Xizang Plateau.” It’s the first time the news site, known for its more internationally-oriented stories, has replaced “Tibet” with the transliterated Chinese name for the region.

English-language state media have slowly been making the shift since late 2021, as part of a Party directive to make Tibet sound more like any other Chinese province (and less like a historic kingdom) in external propaganda — something we wrote about in greater detail in late 2022.

The shift has been gradual, not just across publications but also within them. Caption writers at the Global Times can still be found using “Tibet” in recent weeks and months, more than two years since the transition began in September 2021. In some cases, editors have resorted to “China’s Tibet,” or have awkwardly used “Xizang (Tibet) Autonomous Region” in an apparent effort to bring readers around to the new nomenclature.

The change, however, seems unstoppable in the state media. Since we wrote about the emergence of “Xizang,” other publications like China Daily, published by the State Council Information Office, and the English-language version of the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily have also hopped aboard.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

A Mighty Voice

Dasheng (大聲) is a new online outlet that is trying to curate high-quality Chinese-language media and create a community that will help nurture the next generation of journalists. We spoke with founder Vivian Wu, a Chinese journalist with decades of experience in the industry, including a stint as bureau head for the BBC World Service in Hong Kong.

Lingua Sinica: What inspired you to go from working with global media like the BBC to launching a new, independent platform?

Vivian Wu: When I started to work as a journalist 20 years ago, I was one of the very lucky few mainland Chinese who got a chance to work in English-language media. A lot of professional standards common to Western media were unheard of in China, but the country was also seeing a robust growth of civil society that was supported by a more developed media space and free internet discussion. The country was moving forward at an incredible pace and leapfrogging from a hollowed-out newspaper industry to a robust digital space, outpacing the West in some areas of technology. Since Xi Jinping took power, we’ve been seeing the disappearance of independent media and civil society organizations, lawyers, and civil rights defenders.

I think that training as a journalist is something that Chinese society needs to move in a more rational direction. When I was running the BBC bureau in Hong Kong I realized that despite the downfall of civil society, people still needed good journalism. But not the old models. It’s time to rethink, to reconstruct. It’s time to find out what we need. No one cares about writing good content anymore and we’ve also seen a corresponding fall in the quality of information.

I want to bring together all the traditional media training I benefited from, support individual journalists, give peer reviews, create a curatorship team and a bulletin of the best content produced in the community, and create a comfort zone for people who have a shared system of values. It’s self-salvation and also a mutually supportive peer community that is open to everybody. This way, we can rescue the narrative and skill sets and bring together people from around the world who have been suffering from physical separation and psychological isolation.

LS: Although you say this is something Chinese society needs, that’s an audience for Dasheng to reach, as a critical outlet on foreign social media platforms. So who do you see your audience as? Is it diaspora and exile communities, or people in places like Hong Kong and Taiwan?

VW: It’s a mix. Right now most of our visitors are coming from the US and about a fifth are from China, but it’s always difficult to tell how many international hits are actually from PRC-based readers using a VPN.

New diaspora communities have become a trending topic as outflows of emigrants have increased recently. This is also one of the reasons why I gave up my global media job and decided to do a start-up: I want to create something that is owned and supported by the Chinese community, not just translations of stories produced by the BBC or The New York Times.

It's time for professional skills. It's time for people to actively consume good quality content rather than passively consume small, social media-driven pieces of content. There's a huge market demand for that. American Chinese, for example, complain about how superficial international media on China can be, but the alternative to Chinese state media is Falun Gong-run media also rife with misinformation and disinformation. So they give up on reading about China in Chinese.

LS: At this point do you have a revenue model in mind or are you working on grants from foundations?

VW: I want to try all kinds of models. If you pursue grants, these could be available for a only certain period and then you become limited or too constrained by the grant's direction.

I want to do a combination. We will have a membership program, we’ll sell tickets for events, redistribute content, accept sponsorship and advertising, host book and film reviews, and build an online book distribution system. So it will be a hybrid with different lines of income. I don't think in one or two years we can be financially independent so in the meantime, we are open to grants and donations.

STORYTELLERS

China’s Most Important Variety Show

In the People’s Republic of China, the Spring Festival holiday is a time when all the family, young and old, gather around the television screen to tune into the Spring Festival Gala (春晚) on the state-run China Central Television (CCTV). Still staple holiday viewing, the broadcast is for most the only time of year when the entire family can turn to the same entertainment program, and join in the laughter.

But how did this tradition begin? And are the funny moments quite as funny as they used to be?

Bumpkins and Banquets

Started in 1983, the Gala rose to popularity in large part through its comedy sketches, which were performed between song-and-dance numbers. This is where some of China’s biggest names in comedy — entertainers like Song Dandan (宋丹丹) and Zhao Benshan (赵本山) — made their names.

While the colorful extravaganza certainly cleaved to broader policy themes, it was rarely in its early days steeped in political reverence — and at times could tip toward the irreverent in ways that delighted audiences. In the 1990s and 2000s, sketches poked fun at the Chinese living out the reality behind the lofty political rhetoric. Archetypal country bumpkins missing their two front teeth, for example, could boast that their pearly whites had been “gloriously laid off” (光荣下岗 ) — a common term in the 1990s for the millions laid off as state-owned enterprises downsized in a push for privatization. Hoggish local cadres were mocked for the lavish banquets they threw themselves. And migrant workers, often valorized in state propaganda as the engine of manufacturing, could be depicted as threadbare and on the run from the family planning authorities for violating the One-Child Policy.

It was possible still, in the 2000s, for critics to see Zhao Benshan’s antics, and the guffaws they elicited, as “cultivating a critical consciousness for the continuing creation of democratic sensibility.”

A New Era for the Gala

But as with most forms of public entertainment in the past decade, the party-state has become more closely involved in the annual ritual of the Spring Festival Gala — and for some, the laughter is fading. Though still viewed in huge numbers (11 billion across all media in 2023), for many today the sketches just aren’t as funny as they once were.

While the program still attracts talent, and there can be good moments — as in Jia Ling’s “Three Twists and Turns” (一波三折) from 2021 — much of it comes across as sugar-coated official messaging. Even highlights like Jia’s antics must finish off with public service messaging, in her case the essential importance of physical fitness and regular health checks.

The creeping changes have been noted since at least the start of the Xi Jinping era. As one columnist rued in the Xinhua Daily Telegraph in 2014: “The Gala has become ultra symbolic, ceremonial and even political . . . . For the gala to reform itself, the only path ahead is to return to its origins." And in 2022, when the focus of the Gala was technological innovation and Xi Jinping’s stringent zero-Covid policy, another Chinese viewer summed it up this way: “The Spring Festival Gala has its political role; it has its propaganda role, but it just has no real role in entertaining the public.”

DID YOU KNOW

“Chinese New Year” Goes by Many Names

Every year, the old debate resurfaces: should we call the upcoming holidays Chinese New Year or Lunar New Year? Or Spring Festival?

The debate doesn’t bear relitigating here. But readers may be more interested to learn that there’s no consensus even in Chinese on what to call the most important date in the calendar. Without even accounting for the diversity of diasporic communities around the world, well-wishers are liable to call it different things in China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

While “Spring Festival” (春節) does come up in Taiwan on occasion, only in the PRC does it achieve true ubiquity. Despite its association with millennia-old traditions, the term itself is surprisingly modern. It dates from calendric reforms introduced by Yuan Shikai (袁世凱) in the first years of the Chinese Republic.

A Man for All Seasons

Yuan decreed that, from 1914, the country would observe four national holidays — one for each season. First was the Lunar New Year, which was to be renamed Spring Festival. Dragon Boat Festival (端午節) would then become Summer Festival (夏節); Mid-Autumn Festival (中秋節) would be Autumn Festival (秋節); and the Winter Solstice (冬至) was to become Winter Festival (冬節).

The collapse of Yuan’s government, however, as he tried to crush the Kuomintang and install himself as emperor, meant these reforms never got very far. The country was fragmented once again, and even after the success of Chiang Kai-shek’s Northern Expedition, China was faced with internal strife and encroachment by Japan. When Mao’s Communists won the civil war in 1949, they decided to keep Spring Festival but jettison the other seasonal holidays.

A British colony since 1842, Hong Kong was spared all this political drama and strongmen leaders trying to leave these marks on ancient traditions. Colonial authorities took a light touch when it came to local traditions — too light a touch, many in London would later allege. Spring Festival, therefore, is almost unheard of. Hongkongers are much more likely to simply wish you a “happy new year” (新年快樂 san1 nin4 faai3 lok6) or, of course, prosperity in the next lunisolar cycle (恭喜發財 gung1 hei2 faat3 coi4).

Whatever you happen to call it, happy new year! See you all again in the Year of the Dragon.