Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 6 February

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

And welcome to the Year of the Snake.

We may be back to work now but with Lantern Festival (元宵節) still a week off, it’s still very much the New Year season — so we’d like to once again wish all of our readers a very happy Lunar New Year. Or is it Chinese New Year? With a regularity as predictable as the new year itself, that question has once again preoccupied news and social media for the past few weeks.

The biggest flashpoint this time around was a Chinese milk tea chain that uploaded social media posts featuring the phrase "Lunar New Year" instead of "Chinese New Year." A pile-on by online nationalists, who saw the message as a move towards “de-Sinicization” (去中國化) — followed by the obligatory public prostration by the brand itself.

As political sensitivities over who is and is not “patriotic” enough continue to rile Hong Kong, the issue has also taken on renewed urgency there. Chief Executive John Lee was careful to use “Chinese New Year” in his official English-language missive on New Year’s Eve — even though two previous iterations had used “Lunar New Year.” HK01 reported on the same day that Hong Kong does not have a mandatory English translation for the holiday’s name, and that “the use of Chinese New Year this year reflects the high political sensitivity of Lee and the CE's office.”

In an interview with UK-based diaspora news outlet The Chaser (追新聞), Hans Yeung, a scholar and former official with the government examination authority, said that the English translation of the holiday has lately become politically contested, and that “Lunar New Year” had been the usual translation in Hong Kong during British colonial times. The state-run Ta Kung Pao (大公報) newspaper also chimed in, writing that “Lunar New Year” is “clearly inaccurate” and throwing its weight behind “Spring Festival” — a distinctly mainland nomenclature that, for reasons I explained in last year’s seasonal newsletter, never caught on in Hong Kong.

For my own part, I quite effortlessly code-switch between saying “Chinese New Year” with friends and family in Hong Kong — where the holiday’s culturally Chinese origins are largely accepted and seen as apolitical — and “Lunar New Year” with friends here in Taiwan, where it is the preferred term for most who want to celebrate the holiday without compromising their sense of national identity. In Chinese, of course, it’s not even a question — it’s just the “New Year.”

Nationalists argue that “Lunar” is inaccurate since the traditional agricultural calendar (農曆) is lunisolar. They have a point. But associating this ancient, almost pan-Asian set of traditions with a single modern nation-state isn’t exactly accurate either. If both are compromises, can’t we all add a second compromise and admit that both can be appropriate in different circumstances?

Like the perennial debate about whether we should call China’s ruling Communist Party the CCP or the CPC, there is little substantive difference. Taking a militant stance ultimately says much more about the person arguing than it does about either of these two dueling terms.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

IN THE NEWS

Flu Season in Japan Claims a Taiwanese Star

A report by CommonWealth Magazine (天下雜誌), one of Taiwan’s top professional outlets, casts light on a recent flu outbreak in Japan, brought into keen focus this week by the tragic death of a beloved Taiwanese entertainment figure. Barbie Hsu (徐熙媛), the 48-year-old star remembered tenderly for her role in a popular teen coming-of-age drama, passed away on February 3 from pneumonia complications related to flu during a trip to Japan over the Spring Festival. Hsu, also known affectionately by her stage name “Big S” (大S), rose to pan-Asian fame in 2001 with “Meteor Garden” (流星花園), a show set in a high school and starring the members of the Taiwanese boy band F4.

According to Japan's health ministry, the flu season in recent months has been severe. From September through to last month, Japan recorded more than one million flu cases. The situation reached a critical point at the close of the year, when weekly flu cases hit a 26-year high of nearly 2.6 million — out of a population of 125 million, of which nearly one-third are over the age of 65.

No Intrusive Reporting, Please

While the Commonwealth piece focused on the dangers of flu, and preventive measures for travelers, the headlines in Taiwan have buzzed this week with drama-filled reports and tributes to Barbie Hsu. For example, many media, including Taiwan’s Central News Agency (CNA) reported the grief of her ex-husband, Chinese businessman Wang Xiaofei, as he rushed to Taiwan from Thailand after hearing the terrible news. Reporters were gathered waiting as Wang arrived at the Taoyuan International Airport, and quoted him as saying with emotion that "she will forever be a member of my family."

In response to the wave of prying coverage on the day of Hsu’s death, Taiwan's National Communications Commission (NCC) issued a reminder to media to avoid “intrusive reporting” (侵入式採訪), saying that media should respect the privacy and feelings of family members, avoid sensationalized reporting, and follow guidelines for journalistic self-regulation.

IN THE NEWS

Micro-Dramas, Mega Ambitions

In our last issue, we covered how micro-dramas — TV series cut into minutes-long segments and optimized for mobile — have become huge business in China, and increasingly an area of interest for the country’s censors and propagandists. The National Radio and Television Administration, or NRTA, the ministry-level broadcast regulator under the Party’s Central Propaganda Department, rolled out plans in January for a micro-drama on Xi Jinping’s political ideology, and it has signaled that it will start regulating the space more heavily in future.

Then, on January 21, the inevitable happened. China’s mania for micro-dramas crossed streams with the leadership’s grand new strategy for boosting external propaganda by leveraging international communications centers (ICCs) opened by local governments. Zhujiang College, a satellite campus of Guangzhou’s South China Agricultural University (华南农业大学), unveiled its new “Bay Area International Micro-Drama Development Research Center” (湾区国际微短剧发展研究中心). Like other such centers hosted at universities, it aims to tap into the creative potential (and, one hypothesizes, cheap labor) of its student body to appeal to younger audiences.

Micro-dramas are nowhere near as popular overseas as they are inside China, but propaganda officials are banking on that changing soon. And by developing China into a micro-drama powerhouse first, they will be well-positioned to shape the new medium’s trajectory worldwide. In an interview for the university’s in-house news service, the center’s director Jin Tao (金韬) said that even though micro-dramas had not taken off abroad, their success in China “foreshadows [the medium’s] international influence.” He urged those creating micro-dramas to produce videos that “can guide viewers to think and transmit positive energy” — a byword for pro-CCP content.

How China Built Its African Media Empire

The name StarTimes is little known in the West. But in thousands of villages throughout rural Africa, it is plastered across satellite dishes and television sets. From its humble beginnings as a cable installation company in Hebei province, it has become a key part of China’s strategy to shape conversations about the country and advance its interests across the continent.

Today, StarTimes is one of Africa's media market leaders, vying for dominance with France’s Canal Plus and South Africa’s Multichoice. Its content fills the screens of millions of African homes and it has become synonymous with football, serving as the exclusive broadcaster of Ghana’s Premier League. The group has attracted attention in academic circles but its history, operating structure, and the part it plays in China’s broader foreign policy goals are not widely known. Piggybacking on the Belt and Road Initiative, it has become the media face of Xi Jinping’s mission to extend the PRC’s economic and political influence in developing countries.

In an in-depth feature next week, we take a considered look at the ongoing StarTimes saga. Make sure you’re subscribed to Lingua Sinica to get the full story.

Content Sharing in Guinea-Bissau

Some in the small West African country see China as the partner who “never interferes”

In an interview with Chinese state media this week, Amadu Djamanca, the head of the state-run national television network in the small West African nation of Guinea-Bissau, one of the world's poorest countries, expressed an interest in deepening media cooperation with China. Djamanca called for more content-sharing and personnel training between the media sectors of the two countries, and suggested, according to Xinhua’s paraphrasing, that “China actively promotes African voices on the global landscape, providing African media outlets with opportunities to share their narratives.” These comments closely echoed the criticism Chinese state media have frequently directed at Western media dominance — criticism that positions China as a champion of the developing world.

China’s influence in Guinea-Bissau has steadily grown since it supported the country's struggle for independence in the 1970s. Beijing has financed the bulk of major infrastructure in the country of two million, including roads and government buildings, and has provided both agricultural and medical aid. In the area of media, China has supplied broadcast equipment, funded digital TV projects (like the 2017 partnership with StarTimes), and provided training and junkets for journalists and officials (including Djamanca). During a visit to Beijing in July last year — when the bilateral relationship was announced as a formal strategic partnership — Guinea-Bissau’s president praised China as an "indispensable partner" that "never interferes in the internal politics of an African country." During that visit, the state-run China Media Group (CMG), directly under the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Propaganda Department, signed two separate cooperation memorandums with Guinea-Bissau's national television and radio stations.

Against rosier appraisals of the relationship, however, some local experts have warned about Guinea-Bissau’s growing dependence on China. They have noted the lack of transparency in bilateral agreements and China's increasing control over the country’s natural resources. For China, media engagement and diplomacy abroad is a crucial strategy to ensure it can better drive the conversation over its interests.

HONG KONG IN FLUX

Farewell, Political Neutrality

All public servants must be national security enforcers, Hong Kong’s security chief says

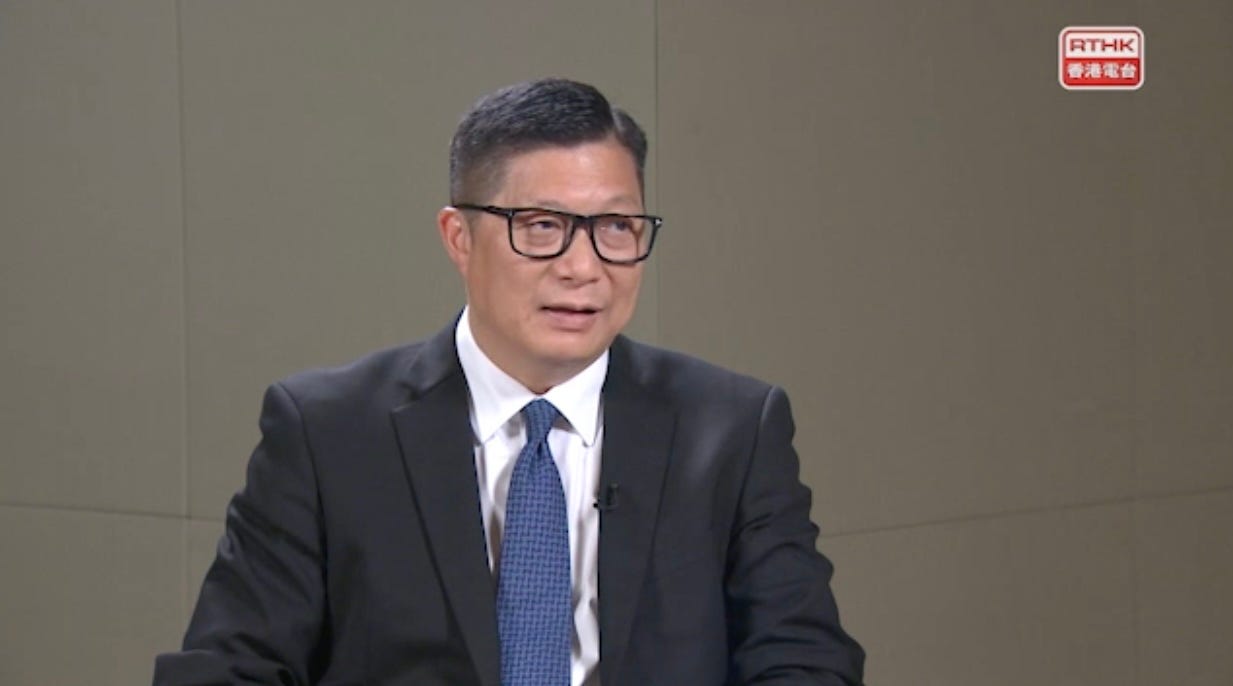

In an exclusive interview last month with RTHK (香港電台), the Hong Kong public broadcaster that has been brought to heel since 2021, the territory’s secretary for security, Chris Tang (鄧炳強), sharply criticized the notion that civil servants were simply professional functionaries that should maintain "political neutrality" (政治中立). Instead, he insisted, all civil servants in Hong Kong have a responsibility under the National Security Ordinance to "proactively assist in the maintenance of national security."

The idea that “political neutrality” is, as Tang suggested, “an erroneous concept” (錯誤觀念) is a notable — though perhaps not altogether surprising — shift in the description of guidelines for the conduct of civil servants in Hong Kong, which for decades has enjoyed a reputation for a highly professional and functioning civil service. Before the territory’s Civil Service Code (公務員守則) was updated with new national security provisions in June 2024, this “erroneous concept” was sacrosanct to the authorities themselves, who cited the code’s political neutrality clause to terminate government staff who supported democracy movements in 2014 and 2019. It was also used to justify the crackdown on RTHK itself, since its employees are civil servants.

Back in November, Tang announced that new guidelines, not to be shared publicly, would be introduced during the first half of 2025 to offer guidance for civil servants on how they were to handle national security cases. Tang’s recent remarks were covered prominently by the exile news outlet Photon Media, which reported that the new guidelines feted by the security chief will cover 20 aspects of national security and delineate their connection to the work of civil servants.

MEDIA BUZZ

A Windfall for Taiwanese Media?

As lawmakers reported for the 11th term of Taiwan’s Legislative Yuan this week, members of the opposition Taiwan People’s Party (民眾黨), or TPP, indicated that media reform would be one of their priorities this session. TPP lawmaker Chang Chi-kai (張啓楷) told the state-funded Central News Agency (中央社) that they will pursue two relevant bills: one on a "mandatory bargaining code” requiring online platforms to pay for news content, and one on "satellite broadcasting and television" mandating the disclosure of information on media funding ownership.

The former is explicitly modeled on earlier “Mandatory Bargaining Codes” passed in Australia and Canada. These laws mean that platforms like Facebook have to pay news organizations for the content that gets shared on their sites. It’s a way to fix a long-standing imbalance in the media ecosystem — whereby huge tech platforms profit from third-party content on their sites and content creators themselves get nothing — and provide the industry with a much-needed financial lifeline. These measures have been welcomed by news organizations and unions in the affected jurisdictions, although tech giants seem intent on not paying for the content they host: in Canada, Meta banned news content on their platforms. Internationally, they also seem to be preparing for similar legislation by leveraging AI-generated users to artificially drive activity.

It remains an open-ended question what the Taiwanese version of this law would look like. According to documents submitted to the Legislative Yuan so far, legislators are still in the process of researching other models and assembling an inter-ministerial study group. For better or for worse, though, whatever opposition parties decide on is likely to pass with little debate. The minority TPP, together with the main opposition party, the Kuomintang (KMT), currently commands a majority in the chamber. The two parties have been working in lockstep to push through a slew of new laws aimed at undermining the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Last month, the TPP and KMT made unprecedented cuts to the government’s annual budgets, threatening to shut down ministries and take funding from the military at a crucial time.

Stay tuned to Lingua Sinica for more updates on these legislative moves and their possible impact.

SPOTLIGHT

Uncovering a Cross-Border Scam Industry

In a deeply reported investigation published on January 16 through the WeChat-based outlet Positive Connections (正面连接), journalist Wu Qin (伍勤) provided a rare insight into the cyber scam industry along the Myanmar-Thailand border. In recent years, thousands have been trafficked to compounds run by criminal gangs on the Myanmar side and forced to engage in online fraud. The issue was given greater public attention in China and across the region last month as it emerged that a well-known Chinese actor, Wang Xing (王星), had been abducted while in Thailand and held for three days in a compound across the border in Myanmar.

Wu’s story, which required months of on-the-ground reporting in Mae Sot, on the Thailand side of the Moei River, takes an intimate look at the complex infrastructure and mechanics of criminal operations in the region. Drawing on a wide range of sources, Wu’s piece is also noteworthy for how it questions the Chinese public discourse on the scam industry, which has focused blame on Southeast Asian countries despite the fact that Chinese criminal groups are at the heart of operations.

For a taste of Wu’s excellent work, see our partial translation on the CMP website. For more on the work of Positive Connections, see our interview with founder Zeng Ming from three years ago.

FIRST DRAFTS

“Decentralizing” Hong Kong Court Records

As long as the ongoing national security crackdown in Hong Kong has been shutting down major news sources, blocking websites and forcing others offline, Hongkongers have been racing against time to back up important documentary records that might be lost forever. It’s a story I covered before for TaiwanPlus News — I’ll share the video here as a quick backgrounder.

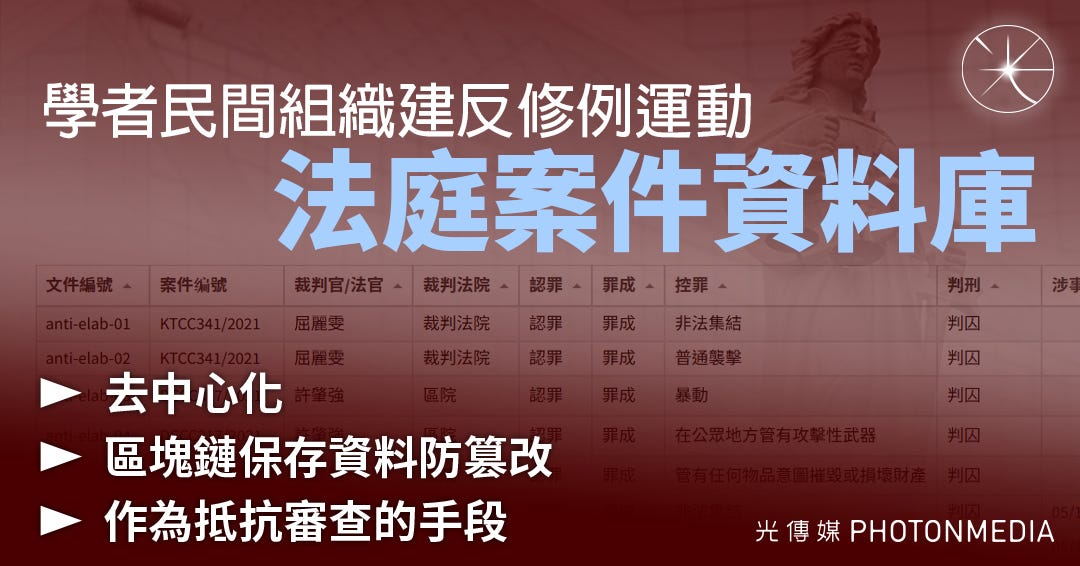

The latest permutation of this mission, however, isn’t looking at a threatened news source. Exile news outfit Photon Media reports that scholars and civil society groups are now working to “decentralize” and preserve court proceedings related to the 2019-2020 anti-extradition bill protests, which morphed over a year into a mass pro-democracy, anti-government movement.

Resilience Innovation Laboratory (RIL), a research platform founded by human rights advocates across Asia, says that their Digital Archiving Project is necessary even though court records are publicly available through the Hong Kong Judiciary. This is because certain cases can involve multiple defendants and individual defendants can face different charges across multiple cases — collating them all in a single file secured with blockchain technology offers an easy-to-use resource for journalists and academics that can’t be tampered with by the authorities.

Despite radical changes in the wake of the national security law imposed by the central government in 2021, the Hong Kong Judiciary remains relatively open with its legal proceedings and records — particularly compared with Party-run courts in the PRC mainland. But as we’re finding out all around the world, little is guaranteed in these times of rapid political upheaval.

FILMGOERS

Hyping a Box Office Boom

According to Chinese state media, the Spring Festival holiday film season (春节档) sent box office records soaring in the country, with the total take reaching 8.36 billion RMB, or about 1.17 billion dollars, for the one-week holiday period from January 28 to February 4. The country's total 2025 box office has already exceeded 10 billion RMB since January 1, and reports claim that so far this year China’s film market has surpassed that of North America, becoming “the world's largest single film market, with over 200 million moviegoers so far.”

Leading the market in China with more than four billion RMB in earnings is the animated feature Nezha Demon Child (哪吒之魔童闹海). The film, which has received strong positive reviews on the film review and social networking platform Douban (8.5 out of 10), is projected to possibly set a new all-time box office record in China, reaching nearly seven billion in total earnings.

TRACKING CONTROL

Disinformation is No Joke

The annual Spring Festival Gala broadcast by state-run broadcaster CCTV is a hallmark of New Year festivities in China, running in the background as families nationwide gather around the dinner table for a brief and boisterous reunion. The hours-long variety show has been running since the 1980s, offering viewers carefully calibrated social commentary and, occasionally, some unforgettable gaffes.

One sketch in this year’s show, airing on January 28, was a dramatized version of the dangers of “self-media” (自媒体), individual user accounts on social media platforms like WeChat that publish self-produced content — and how the country’s top internet control body, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), would like the public to view their ongoing crackdown on such accounts. But the state-run network’s portrayal of independent content creators as purely harmful was itself an exaggeration and oversimplification.

Read the full story at CMP.

CHAIN REACTIONS

A Bridge to Brazil

The Brazilian Chinese Network or BrazilCN.com (巴西华人网), launched in 2009, is a digital platform that aims to appeal, in its own words, to the representatives of Chinese and Brazilian companies, Chinese enterprises interested in investing in Brazil, Chinese expatriates assigned to the country, and members of the more well-established Chinese Brazilian community. The site is a good example of a certain Chinese-language media type we have noted overseas as we have monitoring outlets globally — a site that combines appreciable services to diasporic Chinese while serving, willingly or not, to amplify information from China’s Party-state media globally.

Content on BrazilCN.com is an interesting mixed bag. Along with job listings, housing ads, dating personals, and information on local events and community services — offerings that have real utility and relevance for ethnic Chinese living beyond the PRC’s borders — the site offers content in Chinese from local Brazilian media. At the same time, it boasts that it is “well-received” by the PRC embassy in Brazil, and that it “cooperates” with the Chinese Communist Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper as well as other state outlets.

The web portal has offices in Sao Paulo, Brazil as well as Shanghai and Shaoxing, where website operator Shaoxing Meixin Information Technology (绍兴美信信息技术有限公司) is based. The company has a registered capital of one million RMB but has just two listed employees. Its owner and legal representative, Shao Yuanyuan (邵园园) told the People’s Daily in a 2015 interview that the site aimed to “build a bridge for exchange between Chinese and Brazilian businesses and promote economic trade and investment” between the two countries.

ANTI-SOCIAL

A Rude Awakening

As netizens woke up on the fourth day of the lunar new year on February 1 — a day dedicated to welcoming the gods back into one’s home and earning their blessings for the year ahead — a viral new video on the Chinese short video app Douyin (抖音) showed a more troubling kind of home visitation. In the clip, uploaded by influencer Lu Jiujiu (鹿酒酒), a young woman named Xiao Li (小丽) wakes up to find her room filled with relatives and a strange man, bearing gifts, looming over her bed. The man, we are told, is a blind date she previously agreed to be set up with by her family.

As the story was picked up by Chinese media, the shock value was on full display. “I was completely baffled,” Xiao Li was quoted as saying in one interview. “I didn’t expect him to turn up in my bedroom.” In another unsettling detail, she added that she had no idea how he got in, as her door was locked. The next day, however, as a wave of netizens called the clip’s authenticity into question, Lu Jiujiu confessed in a comment that it had all been a staged performance “for entertainment only.”

Not everyone was laughing. The holiday now past, Liu’s case is a cautionary tale about the dangers of fakery for entertainment. For online creators to truly prosper in the Year of the Snake, appeasing the gods of wealth and the kitchen won’t be enough — here, the gods of the internet decide your fate.

Find the full story on the CMP website.

Calling it Chinese New Year is chauvinistic and derogatory to other countries that celebrate the holiday at that time. Most US residents understand the term Tet, so if the Chinese don't like Lunary New Year, let's use Tet.