Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 23 January

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

The past two weeks have been fraught with uncertainties — a generalization that applies virtually everywhere on earth, as US allies and adversaries alike wonder what the next four years dealing with an erratic “Trump 2.0” presidency will look like. As democratic backsliding affects much of the world, we in Taiwan have a tendency to smugly look around and pat ourselves on the back for the strength and resiliency of the country’s hard-won democracy.

But lately, looking in the mirror has become less comforting. Taiwan’s legislature has turned even more chaotic than usual, with opposition parties — who together command a majority in the chamber — forcing through unprecedented budget cuts that the ruling party has warned could cripple key day-to-day functions of the government, from national defense to keeping gas prices low. And the media haven’t just been covering the story closely — they’re at the heart of it.

Huge cuts to public broadcaster PTS (公視) were on the table — cuts so big they would force PTS and all its offshoots to shut down entirely. These include their main news, drama, and children’s channels as well as channels broadcasting in the Taiwanese and Hakka languages and TaiwanPlus, an English-language channel founded in 2021 to “bring Taiwan to the world.” The foremost reason the opposition cited for shutting down TaiwanPlus was a report on the US election in which they described Donald Trump as a “convicted felon.” They alleged that this kind of reporting, which in fact is entirely factual, posed a threat to Taiwan’s national security by threatening Trump’s ego.

I’ve shared my views on this extensively in previous issues, drawing on my experience getting TaiwanPlus off the ground and working there for nearly two years. Today, though, I wanted to draw our readers’ attention to the second egregious error that, the opposition argued, merits the destruction of PTS: a World War II historical drama called Three Tears in Borneo (聽海湧). The five-episode miniseries follows Taiwanese guards at a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp in modern-day Malaysia, where they become accessories and scapegoats in Japan’s atrocities.

As it happens, we sat down with the show’s director and producer last year. They told us that they wanted to help fill in the gaps in people’s understanding of Taiwanese history, particularly its half-century as a Japanese colony. “People’s understanding of what Taiwan went through during the Second World War is very vague,” director Chieh-Heng Sun told us. “For example, people may wonder why there was a consulate of the Republic of China in Taiwan — aren’t we the Republic of China? Why was the ROC at odds with the people of Taiwan?”

The opposition Kuomintang called this “historical revisionism” but we suggest readers check out the series and hear what the showrunners have to say before deciding for themselves if it truly merits the wholesale dismantling of a public broadcasting network. There’s a lot more in this edition, from Singapore to Thailand, and on to Greece. Until the next time, we wish you all a very happy Lunar New Year! We’ll see you again in the Year of the Snake.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

NEWSMAKERS

Copy-and-Paste Journalism

When an off-duty police officer was arrested in Hong Kong last week for allegedly taking upskirt photos, the incident naturally made headlines across the city. But there was something off about some of the reporting: they didn’t seem to be reporting anything new at all, and were simply copy-and-pasting the same terse one-liner from the police force’s public relations wing.

For watchers of Chinese media, however, this is no mystery but a well-established pattern when it comes to reporting touchy news topics. When a major incident or politically sensitive event takes place on the mainland, news organizations are often strictly ordered against “further reporting” — instead, they are sent an official government news release, or tonggao (通稿), which they are expected to carry verbatim. Every news source from local Party-papers to regional commercial outlets and nationwide media, are instructed to follow the lead of the official Xinhua News Agency, even if all they provide is a single-line summary. Doing any original, on-the-ground reporting or analysis of their own is out of the question. This standard operating procedure is nothing new. But after limited media commercialization in the 1990s and 2000s allowed some outlets to cautiously step out of line and attempt to do real reporting in the face of formal press restrictions, discipline has been almost thoroughly restored under Xi Jinping.

The incident in Hong Kong was likely to trip wires for two reasons: it involved not an ordinary policeman but a member of the large and secretive new national security force established to enforce the national security law in 2020, and the officer in question also tried to grab a gun after his arrest. In Hong Kong, though — where reporters get the official line but then run farther with it, adding input from their own networks of sources — it’s still a new and troubling look.

Observing this development, The Chaser, a UK-based media outlet run by Hong Kong diaspora journalists, concluded that this demonstrates how “the media in Hong Kong has evolved from merely practicing self-censorship to serving as a part of the government's propaganda machine.”

REDLINES

Telling Good Spring Festival Stories

With Spring Festival just around the corner, China’s propaganda apparatus is prepping something special for the holidays. The Central Propaganda Department has ordered all local news organizations to send their journalists down to the grassroots and write stories “fully showing the beautiful scene of prosperity in all parts of the motherland.” In other words, they need to show how good things are on the ground — particularly now, at a time when local-level governments and infrastructure are riddled with debt. Journalists have also been instructed to emphasize traditional displays of filial piety and other time-honored conservative values, per Xi’s orders to build a culturally confident nation through China’s “outstanding traditional culture.”

At the same time, the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) is launching a special month-long campaign to clean up the internet over the holiday. In their sights are netizens “deliberately playing up anti-marriage and anti-fertility topics” as well as “fake news” in the form of typical year-end reviews and “hometown observations.” Authorities will also be cracking down on AI-generated “false images” related to the Lunar New Year. For more information on this festive crackdown, see our full rundown of targets in Tracking Control below.

TRACKING CONTROL

Another New Year's Crackdown

China's top cyberspace control body launched a sweeping month-long campaign last Sunday to sanitize the country's online environment and create a “positive online atmosphere” ahead of the 2025 Spring Festival — the country’s most important annual holiday period. The campaign marked the fifth consecutive year of pre-holiday internet actions, according to the Global Times, an outlet under the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper.

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) said in an announcement that the "Qinglang Operation" (清朗行动) will focus on six areas of concern on popular platforms during the holiday period. Prohibitions, notably, including not speaking ill of the annual Spring Festival Gala on the state-run China Central Television (CCTV), a program that frequently prompts controversy, whether it’s the use of blackface to depict Africans or discrimination against women. Also in their sights are netizens “deliberately playing up anti-marriage and anti-fertility topics” as well as “fake news” in the form of typical year-end reviews and “hometown observations.” Authorities will additionally be cracking down on AI-generated “false images” related to the Lunar New Year.

All this is aimed at “creating a joyous and harmonious online atmosphere” over the holiday. If you don’t have anything “joyous and harmonious” to say, it’s better to say nothing at all. But if you must post over the holiday, we’ve created a simple CAC-based reference table to help you avoid online misbehavior:

SPOTLIGHT

Then They Came for the Pollsters

Hong Kong’s ongoing national security crackdown has earned notoriety internationally both for the million-dollar bounties it has put on the heads of political activists overseas and the somewhat unlikely figures it has targetted, from elected lawmakers to local teenagers.

In their latest roundup of most-wanted suspects, authorities also widened their dragnet to include Chung Kim-wah (鍾劍華) the former deputy chief of the Hong Kong Public Opinion Research Institute (PORI), a well-established and highly respected independent polling institute. Chung relocated to the UK in 2022, expressing fears — evidently well-founded — that “the red lines that move arbitrarily will one day target me.” Police have taken in his remaining family for questioning.

Chung isn’t planning on giving up his day job, though. Photon Media, a Hong Kong exile news outlet based in Taiwan, reports that he has now founded a new polling outfit called the Public Opinion Research Project for Domestic and Overseas Hongkongers (海內外香港人民意研究計劃). This will aim to “consolidate and present Hong Kong people’s opinions,” Chung said, and in so doing “carry forward the voices of Hong Kong civil society.” Its Advisory Committee includes other well-known exiles like former legislator Fernando Cheung and researcher Athena Tong.

PORI itself is still forging ahead in Hong Kong as well. The institute has been forced to circumspect some activities for their own safety, vowing to scrap about a quarter of its usual survey questions and make private the results of some others, with those relating to the 1989 Tiananmen massacre among the affected topics. To learn more, check out HKFP’s explainer.

Few things may sound duller or more benign than randomly phoning people to gauge the public mood on various topics, but it hits on a question of existential importance to any regime insecure about its legitimacy: who, besides them, has the right to say what the people think?

NEW IDEAS

READr Mesh

Can a new blockchain service put news choice back in your hands?

On January 17, the Taiwanese data journalism outlet READr launched a news community (新聞社群) called "READr Mesh" that enables media outlets and the public to bypass existing social media algorithms to self-direct news choices. Founded in 2018 by Mirror Media (鏡週刊), an integrated media group, READr is dedicated to data journalism experimentation.

In a post introducing the new service, READr editor-in-chief Chien Hsin-chan (簡信昌) said the basic idea was to give readers more agency in the discovery of news content. News organizations, he said, faced growing problems in the social media era, as algorithms have controlled what content is visible. Using blockchain technology, said Chien, “READr Mesh” is a cooperative model that allows readers to earn “Mesh Points” through continued engagement, which can then be used to support media outlets or unlock premium content with participating media sites.

(MIS)EDUCATION

Are You Minoring in Chinese Media?

The Chinese Media Group (華文媒體集團), a media company under Singapore’s SPH Media, has announced that it is working directly with the National University of Singapore (NUS) and China’s Tsinghua University to launch a Chinese-language media minor track within the Chinese studies major (中文系) at NUS — the first such course in the country focusing comprehensively on Chinese media.

According to SPH Media’s editor-in-chief Lee Huay Leng (李慧玲), the new program, due to begin in August 2025, fills a needs gap in Singapore’s media landscape. At present, only Ngee Ann Polytechnic (僅義安理工學院) offers media courses in Chinese, and all other institutions provide instruction in English. The collaboration with Tsinghua, said Lee, will create a comprehensive program for training journalism and media talent in Chinese. “The media is very important to our society, and Chinese-language media must also have talent to draw on in this area to transmit knowledge and carry on media work,” she said.

According to a report from Lianhe Zaobao (聯合早報), a broadsheet under SPH Media, the group has invited professors from Beijing’s Tsinghua University to teach the compulsory course on “Chinese Media and Society” as well as other specialized courses to complete the five-course program.

The current head of the School of Journalism and Communication at Tsinghua, Zhou Qing’an (周庆安) has, unsurprisingly, spoken out strongly in support of Chinese leader Xi Jinping and the need to adhere to the CCP’s leadership in “media and public opinion work.” Back in 2008, two years after he received his PhD at Tsinghua, Zhou wrote a paper about the challenge of maintaining “public opinion guidance” — code for the CCP’s control of the news — while reporting major disasters.

With a top PRC university committed to “the correct political orientation” taking the lead in this new studies program, one must wonder what else students in Singapore will be learning about journalism.

CHAIN REACTIONS

A Media Odyssey

Two decades ago, in 2005, a Chinese community newspaper began printing in the ancient city of Athens. According to the founder, Wu Hailong (吴海龙), an international trader who arrived in the country from Zhejiang in 2001, there was a “growing Chinese presence in Greece” — and the China Greece Times (希中报) was essential to Athens’ burgeoning Chinatown. The story of the paper founded by “Boss Wu” — as Wu Hailong is called by fellow merchants, according to a profile by Xinhua News Agency — is simple enough. But behind the paper’s modest circulation of 3,000 free weekly copies lies the more complex story of China's expanding media influence in Europe.

While the newspaper focuses on Chinese-language content, it also claims that its Greek language edition — which it has ambiguously claimed is “supported by” the Chinese Embassy — works to "comprehensively and objectively introduce China's development and reform process to Greek society.” In fact, much of the paper’s coverage comes from PRC state media. Over the years, Boss Wu’s newspaper has established content-sharing agreements with several state-controlled media outlets, including the overseas edition of the Chinese Communist Party’s official People's Daily newspaper, the government-run Xinhua News Agency, and China News Service, a news wire operated by the CCP’s United Front Work Department. It’s hardly a stretch to say that the China Greece Times is stretching the sense of objectivity.

The newspaper's political connections were evident early on. In November 2008, its reporters were granted privileged access to Chinese President Hu Jintao's delegation during his visit to Greece.

TIAN JIAN

Journalism Predictions for 2025

Every year, the Nieman Journalism Lab at Harvard University — created to help journalism “figure out its future in an Internet age” — runs a series of takes from top people in the global media industry for their views on the year to come.

CMP now has its own growing platform dedicated to the future of journalism in the Chinese language, and today Tian Jian (田間) ran its own selection of Nieman Lab predictions for 2025 in translation, with additional feedback from Lüqiu Luwei (閭丘露薇), a veteran journalist and 2006 Nieman Fellow who is currently a professor of journalism at Hong Kong Baptist University. Tian Jian spoke to Professor Lüqiu about the impact of AI as well as changes in information consumption, and how journalists and media should respond.

Name: Lüqiu Luwei (閭丘露薇)

Prediction: Traditional media face the reality of changing information access.

Excerpt: "People still need news, but the redefinition of news and news consumption habits have greatly impacted traditional news media."

Issues: Concerning the direction of the media environment in Hong Kong, Lüqiu says there is no sign yet of a turnaround. While trust in news has increased in Hong Kong, the number of people reading news from the media has declined, which can be seen as a challenge, an opportunity, or even a crisis. The same is true for both the English and the Chinese-language worlds. “There is still a demand for news, it’s just that the definition of what news is and habits for accessing news are having a huge impact on the news media in the traditional sense,” she says.

Regarding AI, Professor Lüqiu says use of the technology is so far uncommon in the Hong Kong media, limited mainly to voice broadcasting and data collection. Its impact on the essence of news content has been minimal, and some media remain resistant to AI — the technology’s credibility in reporting, writing, and verification being low. AI, she says, is not yet sufficiently smart to replace human beings in finding news angles. Nevertheless, AI is an inevitable trend. Lüqiu notes that AI courses are on the rise not just in journalism departments but across universities. The overarching trend in Hong Kong, she says, is to encourage students to use AI tools — the focus being on teaching better use of AI for learning and avoiding plagiarism.

Solutions: The popularity of news-related YouTubers suggests the demand for information is still there but changing modes of accessing information are a reality that the media will have to face, says Lüqiu. In addition, the audience's perception of what is newsworthy may be different from that of previous generations, so it is crucial that journalists and media accurately understand the needs of the audience and even change the traditional way of writing or presenting online news and deciding which topics should be covered.

Read the full set of predictions on the Tian Jian Substack and subscribe for more.

IN THE NEWS

American Refugees

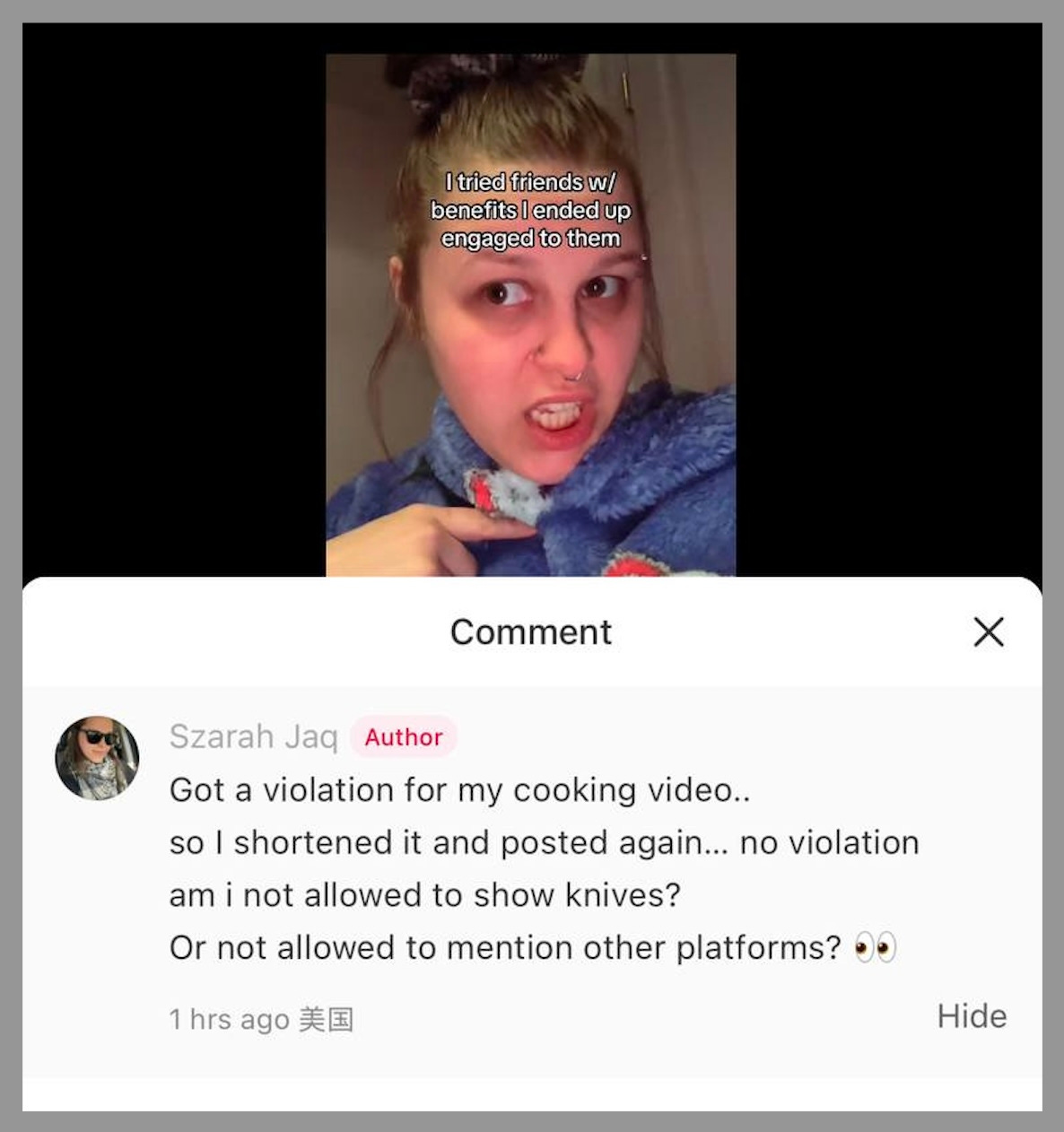

After a year of “Time is Running Out for TikTok” cliches in the headlines, the contentious PRC-owned app has been given a stay of execution in the US, owing to an executive order from President Trump offering a 75-day reprieve on the deadline for it to divest or face a ban.

As that ban loomed, however, many American TikTok users sought refuge in the most unlikely of places: another popular Chinese app that has a long track record of censorship and surveillance. Within a week, more than 700,000 self-styled “TikTok refugees” flocked to RedNote, known at home as Xiaohongshu (小红书) — literally “little red book” — an Instagram-like platform that’s been the go-to for posts on shopping, makeup, fashion, and travel.

If the TikTok exodus surprised RedNote, it has delighted commentators in China, who have cast the event as an affirmation of China’s openness to cultural exchange, and further evidence of the hypocrisy of American values like freedom of speech — which state media have routinely panned over the decades as “so-called press freedom” (所谓的新闻自由). State-run China Central Television (CCTV) declared that TikTok users had found a “new home.”

While US TikTok refugees may have found a temporary harbor and scored a Pyrrhic victory, their enthusiasm could prove short-lived as they grapple with the real conditions on the opposite side of this bridge — the world’s most active and comprehensive system for real-time content moderation and political censorship. Just days into the exodus, there was already clear evidence that censorship mandates are being applied to RedNote’s new foreign users.

Find out more about the TikTok exodus in “American Refugees” on the CMP website.

GOING GLOBAL

A Golden Friendship

On January 17, a high-profile forum on Sino-Thai cooperation in Bangkok brought together journalists, media specialists, and think tank researchers from both countries. Attended by former Thai deputy prime minister Pinit Jarusombat, who in retirement has become a regular on PRC state media, it was also an opportunity for Beijing to outline its vision for media cooperation.

Pinit serves as president of the Thai-Chinese Cultural Relationship Council (泰中文化促进委员会), which was formed in 2020 as a platform for intergovernmental cooperation. He said the dialogue, called “Our Golden Friendship,” aspired to “promote the role of the media and think tanks to better connect people.” But Pinit wasn’t the only VIP in the crowd. Gao Anming (高岸明), vice president and editor-in-chief for the China International Communications Group (中国外文局) run by the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department, was also there to outline China's vision for media and communication — focusing on how to better push PRC agendas in the region.

Gao described media outlets as "important platforms for disseminating information and channeling public opinion.” The latter phrase, emerging under Hu Jintao in 2008, refers to the CCP’s efforts to better direct public discourse toward the goals and agendas of China’s leadership. It is closely related to another term, “public opinion guidance” (舆论导向), which is a crucial phrase in the CCP’s vocabulary on press and information control in China.

Read more about this story at CMP, along with a hilarious hiccup we found when we looked into related CICG outlets.

RED FRUIT

China's Fastest-Growing App

All eyes may be on TikTok and its ongoing drama in the US, but it’s not the only killer app in Chinese tech giant ByteDance’s quiver. The Beijing-based company has developed another streaming service that is dominating the hot new market for micro-dramas (短劇) — TV series cut into bit-sized snippets of between one to 15 minutes.

Hongguo (红果免费短剧) has only been online for about a year and a half, but according to data from analysis firm QuestMobile, it’s already recording the highest growth rate for 2024 of any Chinese app with over 1 million users. In September, it logged a monthly growth rate of over one thousand percent, light-years ahead of the runner-up’s 27 percent growth rate.

The reason for the app’s phenomenal growth rate is simple: micro-dramas (短剧), produced to professional studio standards, for free. As we’ve written in the past, duanju have become hugely popular in China and the market is growing at a blistering rate. Whereas most of their competitors paywall their content, ByteDance streams them free of charge. 36Kr reports that Chinese netizens, tired of forking out every 15 minutes for the next episode, have taken to Hongguo en masse, likely guided there by ByteDance’s multiple other apps. It’s perhaps no coincidence that the second- and third-highest growing apps of over a million users in 2024 were also from ByteDance.

The app is now falling victim to its own success. Late last month, Hongguo halted posting new videos after attracting the attention of National Radio and Television Administration regulators. Later, the developers said they were overhauling their reviewing standards for short videos. On January 10, they announced they had removed over 250 videos with “bad value orientation” (不良价值观导向). Expect the sharper edges of the platform to be filed right down when it comes to the exploration of more sensitive — and interesting — social or political topics.

CLASSIFIEDS

Propagandists Wanted

A job ad in China lifts the lid on the country’s global propaganda efforts

Are you an editor with strong English skills? Capable of striking up relationships with overseas think tanks, universities, and key opinion leaders? Do you have experience working at central state media, or perhaps for an international public relations firm? If this sounds like you, gainful employment is just a click away. Positions are opening in hundreds of centers across China now striving — with some difficulty — to staff up the world’s largest national network for international communication.

On January 10, a little-known Beijing-based publishing company published a list of job vacancies, ranging from English-language social media editors to AIGC specialists.

Read our piece “Vacancies for Global Propaganda” on the CMP website to find out what talents China’s foreign propaganda apparatus is looking for, and what that can tell us about the direction they want to take their work in.

OLDSPEAK

Prejudice with Pedigree

As awareness of gender identity has grown globally, the Chinese-speaking world has not been left out of the conversation. In many ways, Taiwan, famous for hosting Asia’s biggest Pride festivities and being the first Asian nation to legalize same-sex marriage, has been a leading voice for LGBTQ rights in the region. When transgender folks are discussed in the country, the accepted nomenclature is kuaxingbie (跨性別), literally to “cross genders.” A trans woman is a kuaxingbienüren (跨性別女人) or simply kuanü (跨女).

But in Chinese media, particularly across the Taiwan Strait in the mainland PRC, another, more offensive moniker lives on: renyao (人妖). Literally “human monster,” it is variously translated as “ladyboy” or “tranny.” The term is considered a slur according to modern sensibilities, directed at feminine-presenting people assigned male at birth. It has a history that goes back to some of China’s earliest dynasties but continues to be invoked even in China’s official state media to the present day.

Learn more in the full definition for renyao — the latest entry in our CMP Dictionary.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Global Powers, African Stories

The African media landscape has become a contested space where global powers vie for influence and narrative control. While Western media have historically dominated, Chinese and Russian outlets are gaining ground, using their own distinct approaches to shape public opinion.

Amid this competition, local media and audiences are also asserting their agency, pursuing their personal interests, and presenting worldviews that have been uniquely shaped by the region’s past.

We spoke with Dani Madrid Morales, a media scholar at the University of Sheffield, about how China and Russia have been navigating the African media landscape. Below is a single question from that conversation. You can read the full thing on Lingua Sinica or the China Media Project website.

LS: What are some trends in China’s messaging that you’re now noticing?

Morales: In recent years, CGTN Africa has focused heavily on Africa, producing two hours of news daily. But there’s been a noticeable shift. While CGTN used to be somewhat more neutral and pragmatic in the early days, there’s now much more ideological content, especially around Xi Jinping and China’s global influence. They cover the US much more, but it’s usually pretty negative — highlighting flaws in American democracy and social issues. China takes a unique approach to covering Africa: it almost always sides with the ruling party. For example, when elections took place in Mozambique, China’s media congratulated the incumbent before the results were announced. There’s relatively little focus on opposition parties. And just like with other Chinese media, if the government wants a specific topic covered, it will push it.