Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 27 June

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

And welcome back to Taiwan for myself, after a long-ish stay in Hong Kong that began with this year’s International Dragon Boat Races. Like every trip back home since relocating to Taipei in 2021, it was a chance to take stock of the ongoing changes shaking the city up following the imposition of its 2020 national security law.

After a decade of paddling dragon boat races in Hong Kong, as well as mainland China and Taiwan, it was the first time I experienced bag checks for all competitors and saw squads of police in tactical gear constantly patrolling the perimeter. At times, officers outnumbered participants and spectators combined on the East Tsim Sha Tsui harborfront. At a pre-race briefing, we were even warned not to endanger China’s national security and told that paddlers with “ideological” tattoos would be barred from competing. These were dark and sobering moments.

But it was also an opportunity to see how Hongkongers are standing firm by their principles and offering what the government has contemptuously termed “soft resistance.” In independent bookshops, for example, magazine prints from June 1989 were arranged beside books on Beijing, locally-produced candles, and a copy of the Basic Law — the post-handover constitution that, on paper at least, guarantees residents the freedom of assembly. With Tiananmen vigils all but explicitly banned, this is the subtle yet unmistakable language being used to refuse state-enforced amnesia.

Back in Taipei, Lingua Sinica launched our first subscriber-exclusive piece of reporting earlier this week: an in-depth investigation into China-Arab TV, a Dubai-based network that was paraded at this year’s National People’s Congress as a foreign media outlet, but in fact has deep ties to the PRC’s external propaganda apparatus. The piece went out to our paid subscribers first but is now free to view for all, both on the Lingua Sinica Substack and the China Media Project website.

It’s just a taste of the kind of content you’ll get immediate and unfettered access to if you sign up as a paid Lingua Sinica subscriber. Starting July 1, we’ll be rolling out a host of new features and publications for our “Low-Level Red” and “High-Level Black” members — for more information on our subscription plans and how to sign up, check out our post “Become a Lingua Sinica paid subscriber” from earlier this month. This newsletter, in any case, will remain free to all of our readers — enjoy!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

FLASHPOINTS

Pressing On

The Hong Kong Journalists Association (香港記者協會), or HKJA, doesn’t make international news headlines as frequently as the city’s Foreign Correspondents Club, but in some ways its role is even more crucial. Unlike the FCC, it overwhelmingly represents local journalists and has been unwavering in defending press freedom in the city and standing up to the government — a habit that has repeatedly put it in the crosshairs for the authorities and state-run media.

On June 22, HKJA members elected their new executive committee, and attacks against the body have already been coming thick and fast. Even before the vote, Secretary for Security Chris Tang Ping-keung (鄧炳強) personally went after the group, contending that the presence of foreign reporters among the candidates meant that the Association was “unrepresentative” at best, and perhaps even a hostile “foreign force” at worst — a term redolent of attacks from China’s leadership against alleged outside elements (See our CMP Dictionary). Two newly elected committee members have already stepped down.

Unfortunately, this is nothing new. Authorities have been determined over the past few years to make an example of outgoing chair Ronson Chan (陳朗昇), who has been regularly targeted by state media smear campaigns. He also had his home raided by national security police as part of an investigation related to charges of conspiring to publish seditious material, and was later charged with obstructing police after challenging officers who asked to see his ID while he was reporting. None of this is surprising when you look at his CV: Chan worked for both Apple Daily (蘋果日報) and Stand News (立場新聞), the city’s two most prominent pro-democracy outlets, which were both shuttered in the government’s ongoing national security crackdown.

Choosing to put oneself in his position is a bold decision. Stepping up to the challenge, though, is Selina Cheng, a locally-based reporter with the Wall Street Journal. Already, she and the HKJA under her leadership are being attacked by state-aligned outlets — see Chain Reactions below for examples. On Lingua Sinica, we’ve also cataloged how authorities are championing an alternative to the HKJA that believes the media’s role is to “support the government.”

Stay tuned for more on the precarious situation being faced by the HKJA and other press organizations in the region.

REDLINES

The right direction for science is the Party’s direction, says Xi.

In an address this week to scientists and engineers across the country, Xi Jinping hailed strategic national advancements, encouraged greater breakthroughs and innovation— and reminded all of their fundamental duty to abide by the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party.

The address, which appeared Tuesday as a rare Xi-bylined article in the People’s Daily, marked the occasion of China’s national science and technology conference bringing together members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and the Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE). The event also included an award ceremony for scientists doing frontier research.

But leading the talk of “the booming of emerging industries such as artificial intelligence” was a sober warning about fundamental bottom lines.

“The main thing is to adhere to the overall leadership of the Party, and strengthen the centralized and unified leadership of the CCP Central Committee for scientific and technological work, said Xi. This would ensure, he added, “that the development of science and technology always moves in the right direction.”

SPOTLIGHT

The Past is a Foreign Country

Talking about banned books in today’s democratic, pluralistic Taiwan can feel as remote as the world of a dystopian sci-fi novel. But for hundreds of years — from the Qing dynasty through Japanese colonialism and Chiang family rule — that was the reality on these islands.

It’s a reality examined in detail in a recent feature by Singapore-based Initium Media (端傳媒). Special contributor Xiao Zhu (小珠) explores the main types of books that were banned, from the works of “bandit-aligned” authors who remained in the mainland after 1949 to anything on the February 28 Incident — the violent suppression by Kuomintang-led forces of an uprising in 1947 — and the White Terror, the relentless government persecution of dissenters that unfolded over the ensuing four decades. The Initium Media piece also takes a longitudinal look at the phenomenon by speaking to three generations of Taiwanese intelligentsia.

One of these subjects, who speaks about the situation in the 1980s, is Chen Lung-hao (陳隆昊), founder of the pioneering independent bookshop and publishing house Tongsan Books (唐山書店). If you recognize those names, it may be because we recently did our own interview with Chen: “Notes from Underground.” We recommend checking out both this and Initium’s excellent article for more.

GOING GLOBAL

Calling Time on China Minutes

Based in the UK capital, China Minutes (中国时刻) is an English-language outlet that, online and in print, claims to be on a cultural mission. On its website, it says that it aims “to demystify China and make Chinese culture much more accessible, while having fun along the way!” Looking at both its content and ties to the PRC propaganda apparatus, however, there are some basic facts we should be serious about. Let’s take a minute to delve deeper.

China Minutes is the English version of Paris-based Nouvelles d’Europe (欧洲时报), which describes itself as “the most influential Chinese news organization in continental Europe.” In fact, the paper, the oldest Chinese-language outlet in France, is directly controlled by the United Front Work Department of the Chinese Communist Party.

Formally launched in 2015 as a subsection of the official Nouvelle d’Europe website, China Minutes had to wait two years before it got an online home of its own. It frequently runs content lifted straight from state-run outlets like Xinhua and CGTN. Editorially, it also toes the line on topics like Taiwan and Xinjiang. In 2019, the outlet reprinted a Global Times article presenting pro-China perspectives on clashes at Australia’s University of Queensland between pro-democracy Hong Kong students and mainland counter-demonstrators.

On its socials, including a Facebook account boasting nearly 1 million followers, China Minutes tends to focus more on soft-power flexes like pandas, natural scenery, and China-UK friendship. And to an extent, it seems to be working: on Lunar New Year this February, China Minutes hosted a celebration in London’s iconic Trafalgar Square, where Mayor Sadiq Khan posed with a copy of the print edition and reportedly praised the publication for its “positive role in Sino-British cultural exchange.”

More than 10,000 copies of the paper were also distributed to Londoners on the day — few of whom, like the mayor himself, were probably aware of its intimate ties with the PRC propaganda machine.

CHAIN REACTIONS

Sour Oranges

In the wake of the election of a new executive committee at the Hong Journalists Association (HKJA) on June 22, which came amid reports of intimidation (See Flashpoints above), pro-government outlets in the city went on the attack against the group — which has a longstanding reputation for protecting the rights of journalists and speaking out against the deterioration of freedoms in the city. The vitriolic outpouring was a sobering reminder of the fact that provocative political voices that once would have been outliers in the territory have become increasingly normalized.

Among the leading producers of vitriol was Orange News (橙新闻), an online outlet that ran three strongly-worded editorials in the space of 24 hours. In the first, current affairs commentator Liang Wenwen (梁文聞), who has criticized the HKJA for months, wrote that the group “has always in the past upheld the banner of ‘press freedom’ to loudly criticize the government.” Liang’s text was full of air-quote references to “press freedom,” echoing CCP language dismissing the notion as a Western fallacy. In another Orange News commentary, writer Han Jinluo (韓進珞), resorted to a phrase generally seen in the past in CCP criticisms of activists and rights defense protesters: “having ulterior motives” (別有用心). Han alleged that under the HKJA’s newly-elected committee chair, Wall Street Journal reporter Selina Cheng (鄭嘉如), the press group would become “a cheerleading team for the American government” (美國政府的啦啦隊).

Who’s Cheering for Who?

Launched 10 years ago, Orange News describes itself as an outlet “focusing on providing quality information and cultural services in Hong Kong.” What the outlet does not say is that its parent company is Sino United Publishing, which is held by Guangdong-based Bauhinia Culture Holdings Limited (紫荆文化集团有限公司), a central cultural enterprise (文化央企) directly under China’s State Council.

TRENDSETTERS

You heard it here first: China is going local with global propaganda.

It’s been nearly a year since we first wrote at CMP (and at Taiwan’s Commonwealth magazine) about the growing phenomenon of International Communication Centers (國際傳播中心), or ICCs, in China — an effort pushed by the central CCP leadership to intensify and diversify the work of external propaganda by drawing on the resources of provincial media groups.

It is pleasing to see, therefore, that the trend, one of the most crucial in the area of China’s external communication (and in many cases, propaganda and disinformation) is finally getting a trickle of attention. Earlier this week, Voice of America noted the trend in a report that led with CMP research. The article quoted from UK-based experts on PRC approaches to global propaganda more generally. “The battle for discourse power requires all hands on deck,” Jonathan Sullivan, a China specialist at the University of Nottingham, told the outlet.

Want to learn more about this trend? Here is a list of our past reporting:

"More Local Centers for Global Propaganda" / June 12, 2024

"The Local Game of Global Propaganda" / February 29, 2024

"What Does It Mean to Understand China?" / January 4, 2024

"Desert Power, Discourse Power" / November 2, 2023

"Reading China's Media Counter-Attack" / October 5, 2023

“Gilding the Panda” / September 20, 2023

BUZZWORDS

Patriot Genes

In China, references to “red genes” (紅色基因) have become about as copious as the DNA in our bodies. As we’ve documented at the China Media Project, the phrase denotes the revolutionary spirit and history of the Chinese Communist Party as a kind of political and cultural inheritance. While it predates the rise of Xi Jinping, it has become ubiquitous under his rule.

Such abject talk of submission to the Party remains unpalatable, however, in Hong Kong — even four years into an ongoing crackdown on dissident voices and independent civil society. Even the most loyal acolytes know they have to tone it down a bit to appeal to people in the SAR. Perhaps that’s how prominent pro-Beijing figure Stanley Ng Chau-pei (吳秋北) landed on the phrase “patriotic genes” (愛國主義基因).

According to Ng, president of the pro-Beijing Federation of Trade Unions and a post-reform “patriotic” legislator (see “On a Lighter Note” for more context), “Hong Kong has always had patriotic genes.” At an FTU press conference last week, where he called for more public displays of People’s Liberation Army firepower, Ng made the point that love for the country — if not, implicitly, love for the Party — is coded into Hongkongers.

It wasn’t the first time he used this turn of phrase. In fact, he’s made a habit of it over the past few years: targeted searches for the term on local state-run outlets like the Ta Kung Pao (大公報), Wen Wei Po (文匯報), and Dot Dot News (點新聞) turn up several instances when Ng invoked “patriotic genes,” beginning in July 2020 — days after Beijing imposed its national security law on the city. Before then, Ng was one of the pro-Beijing camp’s most vociferous voices, regularly denouncing even mildly critical Hongkongers as “sinners” and “cockroaches.”

Genes can mutate very quickly indeed, it seems, when the Central Government demands.

SCANDAL SHEET

A Top Propaganda Leader Topples From His Mount

In just the second case since late 2022 of a graft probe against a standing official at the provincial level, a deputy minister at the CCP’s powerful Central Propaganda Department, Zhang Jianchun (张建春), was accused last week of “severe violations of discipline and law” — a signal that a corruption investigation is underway.

The decision was announced through the website of China’s top anti-corruption body, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection, but no details of the alleged crimes were given. The news was reported widely across Chinese-language outlets overseas, including Taiwan’s United Daily News and RFI.

Zhang is just the second provincial-ranked, or shengbuji (省部级), official to “fall off his horse” (落马) — this being the colorful phrase in Chinese for being sacked for corruption — since the 20th National Congress of the CCP in October 2022. He is the first senior official from within China’s propaganda system to fall from grace since the arrest in 2017 of Lu Wei (鲁炜), China’s colorful first czar of the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). Like Zhang a deputy minister in the CPD, Lu was sentenced to 14 years in prison in 2019.

Read the full story on the China Media Project website.

ON A LIGHTER NOTE

Good Cop, Good Cop

Four years since Beijing imposed a national security law on Hong Kong and ushered in a period of relentless political repression, some within the pro-Beijing establishment are apparently astonished that not everyone in the city is on-side with the authorities. At a meeting last week, pro-Beijing legislator and erstwhile film producer Ma Fung-kwok (馬逢國) had the solution: “soft selling” Hong Kong’s new legal framework through movie magic.

Ma, who became a member of the Legislative Council in 2022 thanks to “patriots-only” reforms that decimated the ranks of directly elected lawmakers, suggested a cinematic product might bring the public mind around to the glories of greater security. Something like the Hollywood hit Top Gun would be just the ticket, he said.

Tang Fei (鄧飛), a fellow lawmaker similarly returned by new “functional constituencies” created in 2021, not only backed Ma’s approach but did him one better: “Why not shoot,” he suggested, “a national security version of Infernal Affairs” (國家安全版《無間道》)?

As some readers may know, Infernal Affairs is a classic of Hong Kong cinema — a crime thriller about undercover triads and undercover cops that inspired generations of copycats, both locally and, through Martin Scorsese’s The Departed, internationally. The whole point of the film may have been lost on Ma and Tang, though. It certainly went over the heads of mainland censors who demanded its unforgettable, morally ambiguous ending be replaced by one in which all the baddies are brought to justice by the authorities with jarring immediacy:

Is an action-packed national security-themed film in the future for Hong Kong? Stay tuned.

STORYTELLERS

Telling Taiwan’s Story in China

When it comes to discourse on Taiwan, one tends to hear little from across the Strait besides loud, sweeping, and usually aggressive statements from the Chinese government and state media describing how the country has been “an inalienable part of China since antiquity” and “it is the common desire of compatriots on both sides of the strait to draw closer and closer.”

On June 19, however, a WeChat account called “Listen Philosophy” (听哲学) published an essay that offered hopes more nuanced discussions are possible in the PRC, even if they take place more quietly. The piece, by Liao Xinzhong (廖信忠), takes a look back at Taiwanese history to answer its titular question: “Why is Taiwan Gradually Drifting Further Away From Us?”

The author is a Taiwanese who moved to China in 2000, and since then has written several books on Taiwan’s history for Chinese audiences. He said, back in 2011, that Chinese people knew little about Taiwan beyond a handful of famous Mandopop singers. “It seems that everyone is talking about Taiwan, but no one really understands Taiwan,” he lamented.

Since Taiwan was ceded to Japan in 1895, Liao writes, “Taiwan and the mainland have embarked on two different paths.” Taiwanese people’s experience of colonial rule under the Japanese and the authoritarian KMT means they have different values and opinions compared to their counterparts on the opposite shores of the Taiwan Strait, he says — those on either side have little knowledge of each other and cannot see eye-to-eye. In his article, Liao tells readers how many Taiwanese view the KMT, as well as the Qing dynasty and Ming loyalist forces before them, as “colonizers” no more entitled to rule over them than the Japanese, Dutch, or Spanish.

Of course, Liao’s piece is also careful not to touch any red lines. It portrays Taiwan as a Chinese province — one that has its own special history but cannot have its own special identity. It implies this historical drift is a problem that “unification” can resolve. Even so, the points he touches upon show a level of understanding well beyond that of any official PRC mouthpiece.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Angels and Demons

No, we are not talking about a mystery thriller by Dan Brown. We’re talking with Anthony Spires, an Associate Professor at The University of Melbourne's Centre for Contemporary Chinese Studies who is one of the world’s leading authorities on Chinese civil society development — and the author recently of Global Civil Society and China, which traces the history of China’s unstable relationship with global civil society and its values.

CMP Executive Director David Bandurski’s full interview with Professor Spires will be published on the China Media Project website on Monday, but we offer a quick preview here:

Bandurski: In your book, you use this concept, or contrast, of angels and demons to describe China’s conflicted relationship with civil society and its values.

That’s right. It was in this context that Zhao Liqing, a professor at the Central Party School, penned a short analysis asking whether INGOs – and, by extension, global civil society – were “angels” helping China or “demons” out to bring down the CCP and overthrow the state.

Zhao summarized the arguments of the conservative critics of INGOs, but he also noted the positive contributions they had made to China, including funding, new ideas, and new methods for addressing social problems. On balance, he concluded, INGOs were a net positive, although the country still needed to be on guard against potential negative impacts.

Bandurski: National security thinking seems always to be in the foreground in China these days. Having observed Chinese civil society over the past couple of decades, how do you think this security mindset has impacted groups and activities on the ground?

Spires: National security concerns have grown since Zhao Liqing published his article in 2006, and they remain a constant concern not just for the state but also for Chinese civil society groups. NGOs, activists, and scholar-activists have learned they need to be aware of the political wrangling over the desirability of international influences. Leading up to the 2014 Occupy Central and Umbrella Movement protests in Hong Kong, many Chinese NGOs were visited by authorities to check their financial records, demanding they disclose any and all contact with overseas NGOs, including those from Hong Kong.

Just a couple of years later, with the development of the INGO Law in 2016, another wide-ranging discussion of foreign influences took place within domestic NGOs, as well as within academic institutions. There were many academics at universities and at government think tanks who had been beneficiaries of foreign foundation monies, of course, taking overseas trips or being sponsored for short exchanges or periods of study at overseas universities. In short, the overall level of attention, and suspicion of any overseas connections, has just grown in the past 10 years.

With the 2019 protests in Hong Kong, of course, Hong Kong connections were thrust into the limelight again, so nowadays many groups have to be much more circumspect and cautious when considering working with foreign NGOs, even those with approved operations and offices in the Chinese mainland.

NEWSPEAK

Seven Bottom Lines

An important milestone in the PRC government’s restriction of political speech on Tencent’s WeChat (微信) and other social media platforms, the “Seven Bottom Lines” (七条底线), or qitiao dixian, mandates the political allegiance of all users, stating that anyone posting publicly on these platforms must ensure their posts “forge an online patriotic culture, with the soul of online culture resting on the national interest.”

This specialized CCP phrase emerged in 2013 and 2014, as the Chinese leadership’s approach to restricting political speech on social media platforms such as Sina’s Weibo and Tencent’s WeChat (微信) was evolving. It marked a concerted assertion of controls at a time when the Chinese Communist Party struggled to dominate public opinion in a new information world increasingly shaped by internet chatter.

Learn more about the “Seven Bottom Lines” in our CMP Dictionary guest post by William Farris, former legal advisor for Google based in Beijing and Taipei. Check out his wonderful Feichangdao blog here.

CMP HIGHLIGHTS

A Media Labyrinth in the Middle East

What connects the CEO of a Hong Kong-listed online gambling company, a Chinese-speaking Iraqi correspondent, and a former Chinese military attaché in Vietnam? The answer, as it turns out, is: China-Arab TV.

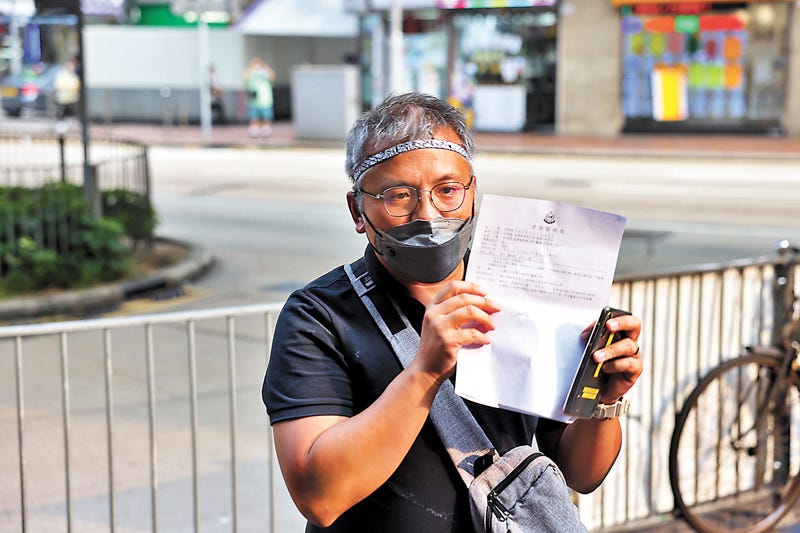

Back at the NPC in March this year, when the correspondent pictured above, Ameen Al-Obaidi of Dubai-based China-Arab TV (CATV), used his rare opportunity during a press conference with China’s Foreign Minister to ask how he and other foreign journalists could “tell China’s story well,” we suspected there was more to the story than just friendliness.

Over several weeks, our investigation into CATV took us on a convoluted adventure from Hong Kong and China to the British Virgin Islands. Read the full story at CMP here, or on Lingua Sinica here.

This report is an example of the type of high-quality work we will be offering more of in the future, with exclusive or early access to our paid subscribers. Support CMP and Lingua Sinica today by becoming a “high-level black” or “low-level red” subscriber!