Notes from Underground

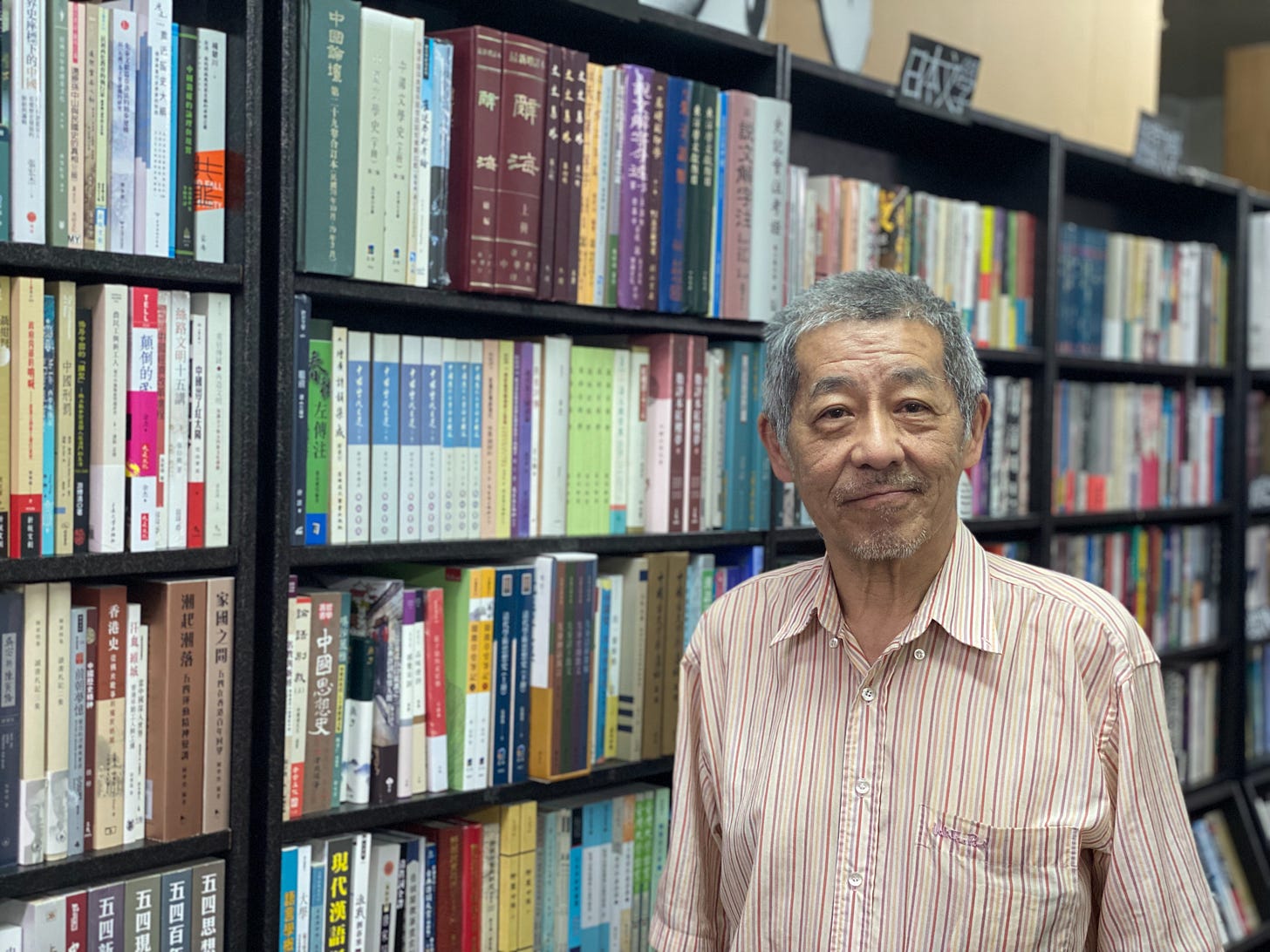

The owner of Taipei's pioneering Tongsan Books tells us what more than four decades in the business have taught him about publishing and bookselling in Taiwan and the wider Chinese-speaking world.

The alleyways and lanes around National Taiwan University in Taipei are a booklovers’ paradise. The triangular area between Roosevelt, Xinhai, and Xinsheng Roads, sandwiched between NTU and nearby National Taiwan Normal University, hosts the most tightly-packed collection of independent bookshops in all of East Asia.

Today, Tongsan Books (唐山書店) is one amongst many of these, but back when it started, it was the pioneer.

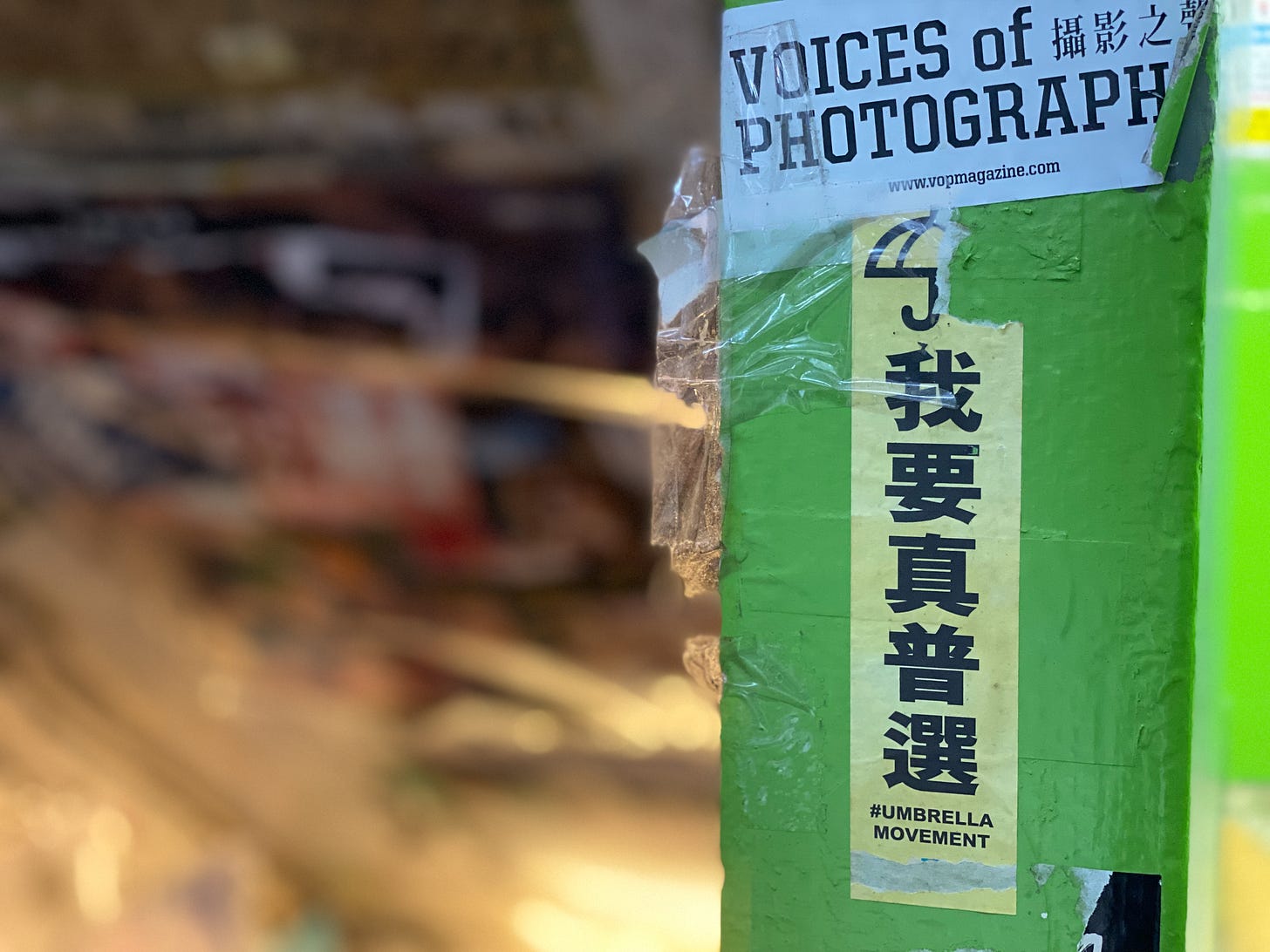

This small publishing house and bookstore first opened its doors in the early 80s, dealing in unauthorized copies and books banned by the then-authoritarian Kuomintang, or KMT (國民黨), government. Decades have passed since Taiwan democratized and businesses like Tongsan stepped out into the sunlight. But it still maintains its distinctly underground aura — literally. Its entrance stands at the corner of two small lanes, where a staircase coated in posters, advertising local events and espousing causes from democracy in Hong Kong to animal liberation, opens up into a cavernous space.

CMP Managing Editor Ryan Ho Kilpatrick recently popped by to chat with Chen Lung-hao (陳隆昊), the local legend who founded Tongsan in 1982 and today still serves as its laoban and a leading voice for the country’s independent booksellers and publishers. This is part five of our ongoing six-part series on the publishing industry in the Chinese-speaking world.

Lingua Sinica: First, tell us about how you get involved in publishing and bookselling.

Chen Lung-hao: I’d just finished graduate school at the time and I was supposed to continue studying, but because of some issues with family at home I couldn’t. I didn’t know what to do. A small guy like me couldn’t do much besides studying.

At that time, though, you could make a lot of money in the pirated books business! Taiwan hadn’t signed onto the Universal Copyright Convention and was still negotiating a bilateral deal with the United States. Unauthorized translations, in particular, were very popular. Taiwan had a terrible reputation for protecting intellectual property but no one cared. Taiwan didn’t care because we needed to circulate this knowledge from the outside world to develop. Americans didn’t even care for a long time either. So many soldiers fighting in Vietnam came here for R&R and needed something to buy, to take back to read. The US just turned a blind eye to all of it. After the Vietnam War ended and Taiwan’s economy took off, we became like China is today. We were selling so much to America and America said, “OK, we’ll buy what you’re selling but you can’t keep pirating stuff — you need to respect our rights.”

LS: Pirating books must have become a lot more difficult after this.

Chen Lung-hao: Yes, after this we began signing copyright protection agreements with the US and Japan, and dealing in pirated books became much more difficult. Taiwan cracked down hard in the 1990s, going from having some of the loosest copyright protections in the world to some of the strictest. In other places, only copyright holders can take legal action against people infringing their rights, but in Taiwan police would grab you off the street if they found you with pirated literature — even if the author had given express permission for their work to be pirated. It was treated just the same as robbery. It wasn’t worth the risk anymore.

Taiwan cracked down hard in the 1990s, going from having some of the loosest copyright protections in the world to some of the strictest.

LS: What kind of books sold best when you got into the business?

Chen Lung-hao: When I first started out in 1982, books on science and engineering and medicine were the most popular, because so many people were studying these subjects. But there were also a lot of people selling as well. The competition was intense. So instead I specialized in books on sociology, politics, and history.

LS: This was before Taiwan had democratized or even lifted martial law. Weren’t these kinds of books politically sensitive?

Chen Lung-hao: There were mainly two types of banned books at the time. The first was books on Marxism, whether we’re talking classical Marxism or neo-Marxism. Second was Chinese writers and scholars who had stayed in the mainland and didn’t follow the KMT. When I started, though, it was already the late stage of the martial law period (1949-1987). It wasn’t as strict as it was before.

LS: Did you ever get caught?

Chen Lung-hao: Police often came by for inspections but we kept most of these titles off the bookshelves. Once, the police bribed a work-study student [who was working at the store] to look at what we had in storage. Luckily, though, martial law was just coming to an end at that time so I narrowly avoided any jail time.

LS: Were there a lot of independent bookstores at that point?

Chen Lung-hao: There are none at first. But they slowly gathered here over time. With so many university students around, it made the most business sense to be here.

LS: Have most of your customers always been university students?

Chen Lung-hao: At first, I saw that the greatest demand is for books in English and academic texts, so this is what successful booksellers specialized in. Even though there are so many students around this area, I’ve noticed a phenomenon: it’s the 20 to 30-year-olds who have graduated from university but haven’t yet married or had children that have the most time and money for books. People in this age bracket actually spend the most on books.

LS: I noticed you have a large section of books in simplified Chinese.

Chen Lung-hao: We actually started selling these a long time ago, before anyone else did. We did this with Hong Kong bookshops. I didn’t have any contact with the mainland but Hong Kong bookshops were selling them at the time. There was this one bookshop in Wan Chai that sold English and Chinese books, and over time we got to know more and more people.

A lot of people in history and the social sciences wanted to learn more about Chinese society through these books. As for whether or not they had a bad influence on anyone, that’s none of my business. My job is just to provide the opportunity to read all sorts of material.

LS: Do you get a lot of customers from China?

Chen Lung-hao: Not as many now as I used to, of course. But years ago, before the pandemic, we used to get a lot — especially during the Ma Ying-jeou years when cross-strait ties were closer. There were a lot of university students from the mainland.

LS: What kinds of books were they mainly interested in?

Chen Lung-hao: Just like mainlanders who used to go to Hong Kong, they’re interested in finding books that are banned in the mainland, that they can’t find over there. This includes a lot of books about Taiwan that are banned over there. As censorship increases in Hong Kong, we’re now seeing more and more Hong Kong people come over as well for this kind of “free speech tourism.”

LS: How have your customers’ tastes generally changed over the years?

Chen Lung-hao: Academic trends have a really big influence. In the 1980s, neo-Marxism became fashionable as a way to separate Marxist theory from what was happening in China and the Soviet Union. In the 1990s, feminism took off. For a while, postmodernism was trendy. Right now, books on China studies are very popular. As cross-strait tensions have risen, people are interested in understanding how the country works and how to escape its influence.

LS: Clearly readers aren’t just interested in China, though. You have big sections dedicated to Taiwan studies as well.

Chen Lung-hao: Yes. When I was young, whether we were studying geography or history, it was always all about China. When I got to high school the Vietnam War was at its most intense, and I could tell you about every province of Vietnam. But I didn’t know where the Dahan, Xindian, and Keelung rivers met [in Taipei] and became the Tamsui River. I memorized all that mainland Chinese history and geography, all that Tang dynasty poetry, but I didn’t know anything about the place where I lived! I didn’t know any Taiwanese poets or authors. Only later in life did I realize how multifaceted Taiwan’s history is, even if it isn’t that long.

I memorized all that mainland Chinese history and geography, all that Tang dynasty poetry, but I didn’t know anything about the place where I lived!

LS: When would you say Taiwanese people became more interested in learning about Taiwan itself?

Chen Lung-hao: Around the change in government, I think — as Taiwan began to be governed by local Taiwanese people. Especially as China has been doing poorly, politically and economically, Taiwanese people have increasingly looked at them as foreigners. They have stopped believing Taiwan is part of China and instead feel that China is China and Taiwan is Taiwan.

LS: How did you decide on the name Tongsan for your business?

Chen Lung-hao: When people from Guangdong and Fujian moved to the South Seas, they talked about going back to “tong-san” (唐山). This was another word for China that was used specifically by southern Chinese people. When I chose the name Tongsan I wasn’t thinking about [the city of] Tangshan in Hebei. I was referring to the parts of South China where most Taiwanese people originated from. It was a name that could be considered politically correct and safe at the time but also had a particular meaning for Taiwanese people.

LS: How is business for publishers in Taiwan these days?

Chen Lung-hao: Not every book we put out can be a success, but overall the publishing industry in Taiwan is flourishing, even though Taiwan is so small and everyone says people in the Chinese-speaking world don’t read books anymore.

The publishing industry in China is all state-owned. There are no private publishers. And in Hong Kong the market is dominated by big, Chinese state-backed publishers like Sino United Publishing, Joint Publishers, Chung Hwa, and the Commercial Press [Editor’s Note: All of the above-name publishing companies are under Sino United, which is directly linked to China’s central government]. When it comes to private publishing in the Chinese-speaking world, especially in traditional Chinese, Taiwan is all that’s left.

When it comes to private publishing in the Chinese-speaking world, especially in traditional Chinese, Taiwan is all that’s left.

LS: I know you used to have relatives in Hong Kong and frequently visited the city. When was the last time you were there?

Chen Lung-hao: The last time I was in Hong Kong was for the Hong Kong Book Fair in July 2020. I don’t dare to go back now, though — it’s not worth the risk.

At the time of the Causeway Books disappearances, I was the head of the Taiwan Association for Independent Bookshop Culture (台灣獨立書店文化協會), so I was there to welcome bookseller Lam Wing-kee when he arrived in Taiwan. He wanted me to help him re-open Causeway Books here in Taipei. I didn’t say I would but journalists began reporting this and [HK authorities] believed that I was supporting him.

They saw me as a pro-Taiwan independence supporter. The [CCP-linked] Ta Kung Pao (大公報) newspaper in Hong Kong ran an expose on me calling me a “black-hearted” bookseller poisoning the youth with extremist ideology. They wrote about how we published the translation of a book for children about fighting for civil rights. [Taiwanese bookstore chain] Eslite also sold the book at one of their Hong Kong branches and the Ta Kung Pao denounced them, too, for encouraging social movements and “promoting anarchism.”

In the West, this would be completely normal. I think it’s completely normal — everyone has rights, don’t they? But the Communist Party wants you to forget your rights.

Thanks so much for this rich and wonderful interview.