When Victims Speak Out

Harassment survivors used social media to expose a teacher's pattern of abuse, but mainstream coverage quickly vanished from China's internet.

Earlier this month, South Reviews (南風窗), a biweekly public affairs magazine published in the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, ran an investigative feature about alleged serial sexual harassment by a high school teacher in institutions thousands of miles apart over a period of more than 14 years between 2010 and 2024. The story revealed a pattern of abuse in the classroom by Chen Jiyong (陳吉永) who allegedly abused his position to pressure female students into forced intimacy, inappropriate touching, and sexual conversations while cultivating an image as a beloved mentor who referred to the students as his "disciples" (弟子) and "little maidservants" (丫鬟).

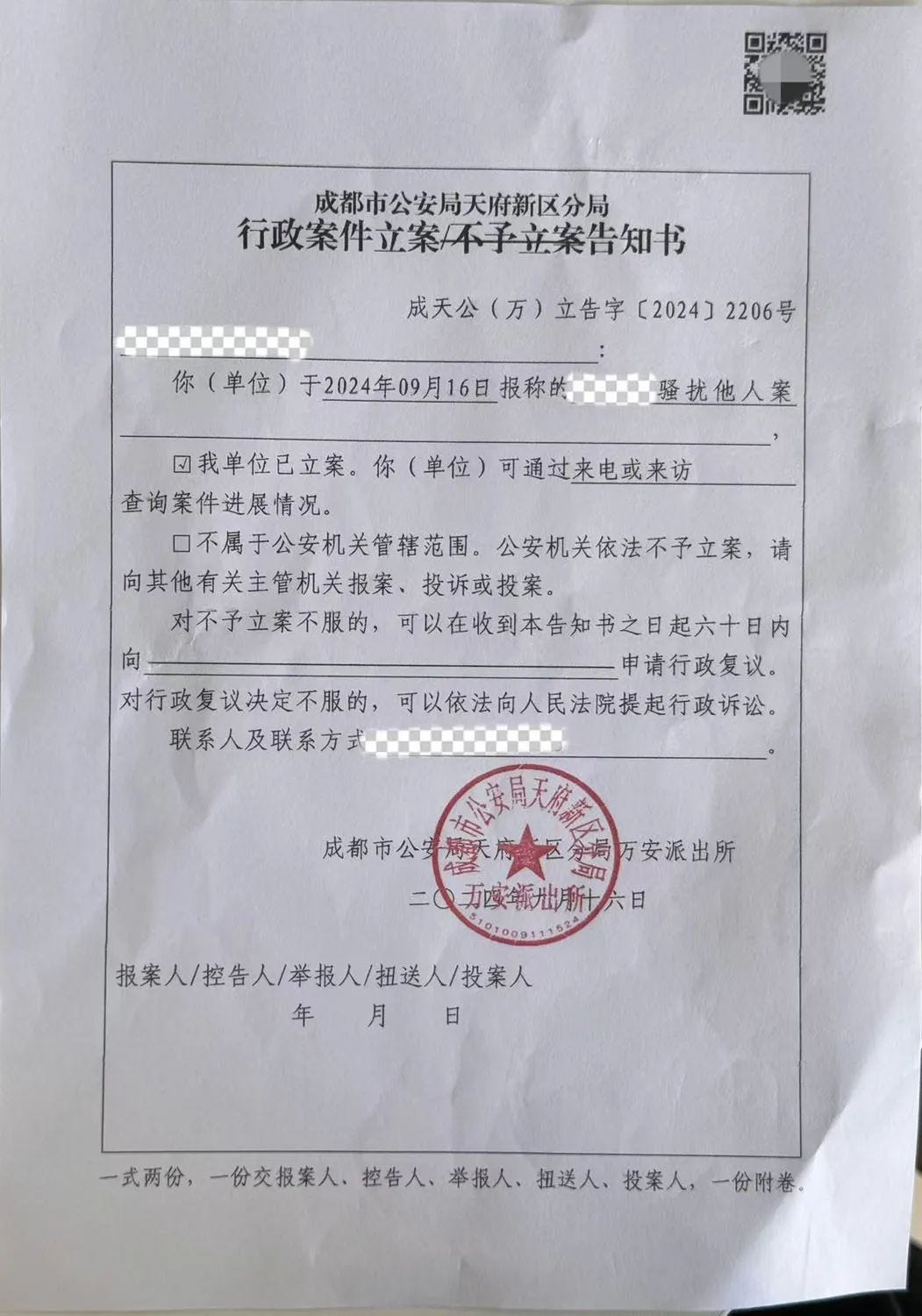

The case also exposed institutional failures that allowed the harassment to continue unchecked: school administrators who dismissed initial reports as "complete rumors," a legal system that rejected cases due to statute of limitations and "insufficient evidence," and educational oversight that enabled Chen to move between schools — from Shihezi No. 2 Middle School in China's far northwest to Chengdu Experimental Foreign Language School — without proper scrutiny, leaving nearly a dozen victims across two provinces with little recourse beyond revoking his teaching license.

The report, "The Girls Harassed by the Same Teacher" (被同一個老師性騷擾的女孩們), offered a rare and detailed account of a problem recognizable and relevant to many Chinese readers. It was, in fact, the only report on the story to appear among major media outlets in China. But within days, it had vanished from the South Reviews website.

The disappearance was a clear sign the authorities were keen to silence a story that invited deeper questioning of a sensitive social issue, and had only managed to surface over the past nine months through the determined voices of the victims.

Glimmers of Truth

Beginning in August 2024, Chen Jiyong's alleged victims came forward to document their experiences through "Glimmer in the Long Night" (長夜微光), a Weibo account they created to this end. Experiences like that of Yuki, a former student at Chengdu Experimental Foreign Language School West Campus, who according to the "Glimmer" Weibo account was called by Chen from an evening study session to a dinner where he allegedly touched her private parts and made sexual jokes during a two-hour ordeal in April 2022.

Only in March this year could the account share publicly that the case concluded with Chen Jiyong's teaching credentials being revoked, though police declined to pursue administrative penalties, citing a lack of evidence.

Within days, it had vanished from the South Reviews website.

The "Glimmer in the Long Night" account, created by victims, gathered evidence and statements from ten accusers. Created almost one year ago, the account posted five different posts documenting the harassment, giving voice to victims' experiences and their ongoing struggles. However, it received limited engagement — the most-shared post garnered just over 6,000 shares, highlighting the challenges of gaining traction for sensitive topics on the Chinese social platform.

South Reviews, a biweekly magazine under Guangzhou Daily (廣州日報), was once described as "a current affairs publication for China's intellectual elite." However, its editorial stance has grown increasingly conservative over the past decade.

South Reviews' report interviewed three of Chen's victims — Yuki, Nicole, and Qingfeng (晴楓), detailing their struggles for justice and the emotional toll of the harassment they faced. They described a pattern of harassment conducted through WeChat, where Chen Jiyong allegedly requested photos and videos from female students while using inappropriate language like "my baby," "I want to have sex with you," and unwanted physical contact like kissing.

Lingua Sinica's companion outlet Tian Jian (田間) interviewed a former contributing writer for South Reviews, who had written several pieces on sexual harassment in the past. She noted that while it's not impossible to write about such topics, no one knows exactly where the red lines are, nor why certain pieces get deleted.“Sometimes it's not necessarily that you can't write about sexual harassment, but if it sparks a big public discussion, then those higher up might decide they don't want it to get too much attention,” said the source.

The deletion of South Reviews' article — the only mainstream coverage of the case — illustrates the narrow space for reporting on sexual harassment in China, leaving social media as victims' primary recourse despite its limited reach. However, the now deleted article is still up on Guangzhou Daily New Flower City (广州日报新花城), the official digital platform of Guangzhou Daily Group — the same parent company that owns South Reviews.