Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 5 December

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

I may have tried our subscribers’ patience in the last issue with my long diatribe on the TaiwanPlus scandal, so this time around I’ll keep my letter mercifully short.

As a brief aside to that story, however, there have been some new developments. The National Communications Commission, Taiwan’s official media regulator, has said it could launch an investigation into the broadcaster if spurred by public complaints. Just to jog your memory, the “scandal” in question here was a TaiwanPlus reporter referring to Donald Trump as a “convicted criminal” — a 100 percent verifiable fact.

The most worrying part of this development may actually be the “initial opinion” offered by NCC Secretary-General Huang Wen-che, who told the Central News Agency that, in his view, the TaiwanPlus report had “harmed the national interest” by potentially pricking the US President-elect’s ego. Needless to say, the job of the journalist is to report the truth, not what is expedient for the government. As I recounted in my last letter, TaiwanPlus was never intended to serve as an official mouthpiece — but if this still-unfolding case sets the precedent that its reporting cannot “harm the national interest,” it might head rapidly in that direction.

But without further ado, we’ll let you get stuck into this week’s newsletter. This edition includes a special three-parter dedicated to the latest developments in China’s international communication centers (ICCs) that have been set up around the country — and now around the world — to help shape the global conversation in the interests of the Chinese Communist Party. It’s a trend we were the first to pick up on and continue to monitor closely, so stay with us until the end to find out more!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

Civilizational Confidence

The Chinese Communist Party’s newest source of legitimacy is its storied ancientness.

The front page of today’s edition of the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily newspaper carries a prominent article attributed to “Zhong Yin” (仲音) that promotes the “modern power” (现代力量) of “Chinese civilization” (中华文明) as a source of “eternal vitality” and confidence. The piece is just the latest in an ongoing propaganda trend since the Party’s October 2022 National Congress designed to reconsolidate the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party and General Secretary Xi Jinping around a grandiose “civilizational” politics.

“Zhong Yin” is in fact an official pen name, a homonym of “important voice,” that marks the article as being produced by a People’s Daily writing group (写作组) to represent the view of the central leadership.

Xi Jinping’s new politics of civilization is an alternative to the GDP-based performance legitimacy that has dominated through much of the reform era. Over the past two years, the CCP leadership has posited that it is the legitimate heir to what Xi calls the “Two Combines” (两个结合) [See the CMP Dictionary], an amalgamation of 1) the adaptation of Marxism to China's "material conditions," and 2) “China’s outstanding traditional culture."

Internationally, China uses this “civilizational” discourse to suggest it is uniquely ancient and wise, offering a development alternative to that of the young and inexperienced (this is the subtext) democracies of the West. In the CCP’s rewritten civilizational history, China has always been central, and a bringer of friendship and prosperity. As it notes the opening last month of a new Chinese-built container port in Chancay, Peru, for example, the “Zhong Yin” piece suggests — quite misleadingly — that a “China Ship” (中国之船) loaded with silk and porcelain first sailed to Latin America in the second half of the 16th century. Any ceramic-laden ship corresponding to this tale, first mentioned by Xi Jinping last month in his speech to the 31st APEC Economic Leaders' Meeting in Peru as “a precedent of friendly exchanges between China and Latin America,” would almost certainly have been dispatched by the Empire of Spain.

AUTHORITARIAN SLIPS

For Whom the Bell Tolls

Could an editorial in Hong Kong state media portend the end of one of its last pro-democracy parties?

Hong Kong’s ongoing political crackdown, which began with the central government’s imposition of a national security law in 2020 and has been shored up since by local legislation, has had a domino effect on the city’s opposition parties. Over the past four years, one group after another has folded: Demosistō (香港眾志), the Professionals Guild (專業議政), Civic Passion (熱血公民), the Civic Party (公民黨). One of the few “pan-democratic” (泛民) parties still standing today is also its longest-establishment and most moderate: the Democratic Party (民主黨) or DP.

In a recent editorial in the Ta Kung Pao (大公報), however, the state-run newspaper has called for the DP to join the ranks of its now-defunct allies. Even though the party has been locked out of the city’s now “patriots-only” elections, it considers its continued existence an affront. Citing DP members who were among the 47 local politicians sentenced to lengthy prison terms over an unofficial primary election, the writer argues that “the Democratic Party’s stance is incompatible with the important principle of ‘patriots ruling Hong Kong,’” accusing the group of committing “various evil deeds” including “subverting state power in the name of democracy.”

“The only way out,” they conclude, “is for it to disband as soon as possible.”

Being targeted by the Ta Kung Pao in this way is far more than a bad publicity problem in Hong Kong. It is typically the first salvo in an official campaign that ends with the dissolution, expulsion, or imprisonment of the individual or group in their crosshairs. Poison-pen reports by the Ta Kung Pao and its sister paper the Wen Wei Po (文匯報) presaged the arrests of members of the General Union of Hong Kong Speech Therapists in 2021, for example, as well as the prosecution of pro-democracy figurehead Joshua Wong under the national security law.

“It’s almost like you can tell who’s going to be targeted next, by seeing who the ‘pro-China’ media are reporting or lashing out at,” a veteran local journalist told the Reuters Institute.

In a further sign of Hong Kong’s slip toward authoritarianism, businessman and Legislative Council member Benson Luk (陸瀚民), from the pro-Beijing DAB party, suggested last week that Hong Kong should mirror China to create a network of foreign language studies universities that could strengthen training in languages other than English. Citing the example of Beijing Foreign Studies University (BFSU), which has signed deals with central government bodies to assist in “external propaganda” activities, Luk suggested — echoing Xi Jinping — that these new language schools would enable young talent to “tell the story of Hong Kong well in different languages.” Learn more from the exile news outlet Photon Media.

NEWSMAKERS

Trial and Terror

Late last week, Chinese journalist Dong Yuyu (董郁玉) was sentenced to seven years in prison on espionage charges, over two years since he was detained while meeting Japanese diplomats for a meal. It was a heavy sentence for someone who would have been regarded — in another time, at least— as an unlikely target. Dong was a veteran state media insider, having long served as deputy director of the editorial department at the storied Guangming Daily (光明日报).

Despite coming directly under the CCP Central Committee and having long served as a mouthpiece for educated party elites, Guangming Daily also acquired a reputation for professionalism and more liberal-minded ideals during the reform era. Dong joined the paper after graduating from the prestigious Peking University’s law school in 1987. After participating in the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, he was sentenced to a year of hard labor but resumed working at the newspaper afterward.

In the decades since then, the Liaoning native has earned a decent reputation as a journalist and author, but has managed to steer cautiously clear of controversy or open opposition. He was a Niemen Fellow at Harvard University and was also awarded a fellowship and visiting professor position at universities in Japan. He also became a contributor to the Chinese-language edition of The New York Times. But he is perhaps best known for his 1998 co-edited volume Governing China: Choices We Face in the New System (政治中国:面向新体制选择的时代), which compiled essays written by journalists and professors advocating for legal and political reforms in China — and challenged the more nationalist line advocated by hardline scholars in the book China Can Just Say No (中国可以说不).

Dong’s liberal leanings were known, but despite this, he continued to earn accolades from the Party-state establishment. In 2002, he received an award from the state-run All-China Journalists Association (中国记协) for an article praising then-outgoing leader Jiang Zemin and calling on readers to “unite closely around the Central Committee of the Communist Party.” Dong had the cut of a savvy career journalist well attuned to working “inside the system” (体制内), willing to walk up to the Party’s red lines but careful not to overstep them. Few details of the evidence against him are known, but his arrest and sentencing — over, ostensibly, a dinner appointment — illustrate how volatile and hard to avoid those red lines have become.

FLASHPOINTS

A Journalist Strikes Out

The wave of joy that swept over Taiwan on November 24 following its historic victory over Japan in the WBSC Premier12 baseball championship has scarcely subsided over the past 10 days in the country, where the sport is a favorite pastime. Along with the celebrations, however, has come some scrutiny of the conduct of Taiwanese journalists — stemming from a question tossed out perhaps too casually by a reporter to star Taiwan pitcher Lin Yu-min (林昱珉), a member of the country’s Amis Indigenous group (阿美族).

The incident in question unfolded on November 25, the day after the championship game, during which Lin was spotted with a slightly red mouth, causing fans to speculate on whether he was chewing betel nut. This addictive herbal stimulant, which has been called “Taiwan’s chewing gum,” has been somewhat prejudicially associated with the country’s indigenous peoples. Most baseball fans in Taiwan quickly rejected the suggestion Lin had been chewing betel nut. Instead, they said, he was chewing tobacco, a habit he picked up in the United States, where he plays professionally for the Arizona Diamondbacks.

But on November 25, as Lin was returning home via the Tokyo Airport, a journalist for Taiwan’s Chung T'ien Television (CTi) refused to let go of the rumors. As Lin wheeled past with his luggage, the reporter asked very casually and indirectly: “Yumin, can you tell me if they sell betel nut in Japan? Netizens are curious!”

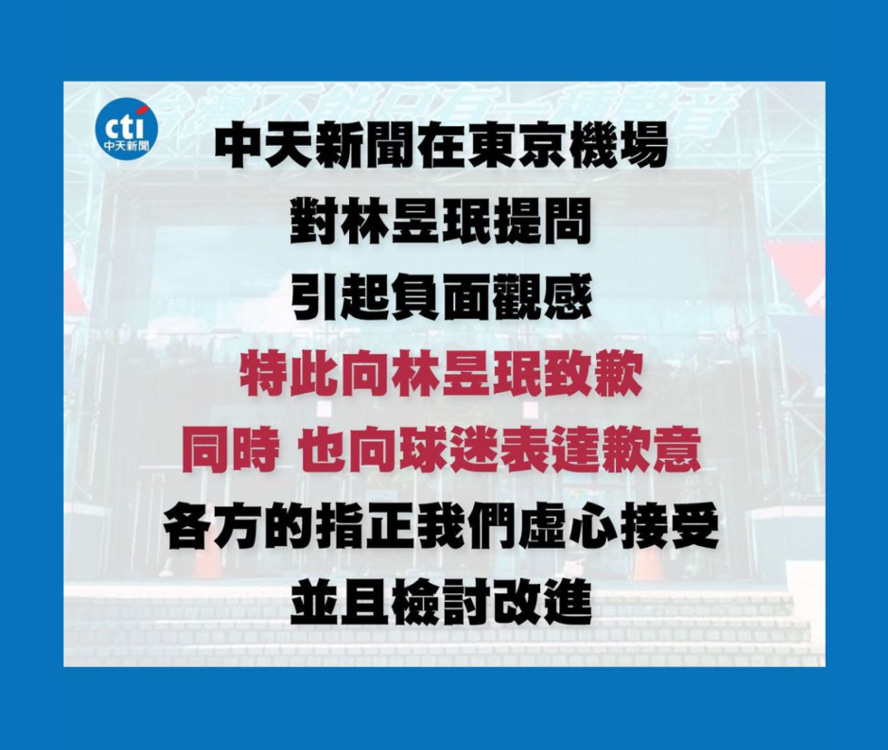

Criticism against the reporter and his network was instantaneous. Many were angry that the reporter, Liang Hao Chang, had not first reviewed the facts. They found his intimate tone both unprofessional and disrespectful. The situation was compounded by the poor professional reputation of CTi among a good proportion of Taiwanese. Later that day, Chang apologized to Lin and his fans through Facebook, pledging to be more thoughtful in the future. Soon after, CTi also issued a public apology over the incident.

Punting on Professionalism

While Chang’s question was not exactly excusable professional conduct, however, it bears mentioning that the incident prompted little in the way of deeper discussion about what constitutes professional behavior. In his apology, the reporter said only that in the future he would be “more cautious” (更加嚴謹), while he appealed to the public not to attack his employer or his family. For its part, Chung T’ien seemed less focused on journalistic ethics than on the bottom line as it apologized to Lin and to “baseball fans” for creating “negative perceptions” (負面觀感). Commenting on the case on Facebook, Cheng Yun-Peng (鄭運鵬), a former member of Taiwan’s legislature, listed several “errors” he said were often committed by “over-eager reporters” (太積極的記者), including assuming people have a right to know, and having a poor understanding of what constitutes the public interest. “I think this incident should serve as a case study for the improvement of news media culture in Taiwan,” he wrote. “It's not just about dealing with sports news.”

Spats like this one over ethical journalism happen regularly in Taiwan. But to date, few media outlets have clear codes of ethical conduct, or clear mechanisms to respond to public criticism in ways that are open and accountable — beyond moral blame and shame.

CHAIN REACTIONS

Silk Road Show

Silk Road News (丝路新闻网) is an Arabic-language online media outlet covering relations between China and the Arab world. A closer look at the outlet — which is populated almost entirely with Chinese state media content — and those associated with it suggests a cozy relationship with China’s government.

According to the website’s "About Us" page, Silk Road News was founded in 2019 by Algerian journalist Abdelkader Khelil, who is also credited as the current editor-in-chief. Jordanian writer Marwan Soudah, a frequent contributor to Chinese state media, is named as the site’s general supervisor. Since 2016, Soudah has also served as president of the International Union of Arab Writers and Friends of China, a group that regularly defends the CCP against its critics, re-publishes PRC state media content in translation, and calls for a “China-Arab strategic alliance” against the West.

Khelil, too, is a familiar face in the PRC’s attempts to control the discussion of sensitive subjects abroad. Xinjiang Daily (新疆日报), the official publication of the CCP Xinjiang committee, reported that he joined a junket of Algerian journalists to tour the region last July. The paper quoted him saying he had “seen the Chinese government’s hard work and achievements in promoting economic development in Xinjiang.”

In 2021, Khelil won the “China Through My Eyes” essay competition, sponsored by the PRC embassy in Algiers to promote positive depictions of the country, and as a reward he got an audience with China’s ambassador. The following year, Khelil represented Silk Road News at the China-Arab Media Cooperation Forum (中国—阿拉伯媒体合作论坛) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, where he joined over 150 delegates from China and 22 Arab nations to discuss ways to strengthen cooperation.

(MIS)INFORMATION

Bogus Bombshells

Last week, reservists in Taiwan were called up for a seven-day training exercise at the country’s National Chengchi University to promote combat readiness in the interest of national defense. The training exercises marked the first time since the martial law period in the 1980s that exercises were held on a university campus, but the response from Taiwan’s public to the news was nevertheless generally lukewarm, prompting little discussion or concern. The only slight note of interest came with a tangential news story, reported by the Liberty Times (自由時報), about former President Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九), who happened to also pay a visit to the university with a delegation of PRC students as the exercises got underway — though the delegation never met with reservists. Such visits by Chinese students are sensitive in Taiwan, where people rightly assume that participants are Communist Youth League members potentially serving as the eyes and ears of PRC authorities.

Pressing PRC Agendas

Despite the relative lack of interest in the story in Taiwan, a strongly worded article appeared on November 30 in Canada’s Chinese Press (華僑網) alleging that Taiwanese felt outraged by military exercises on a college campus. Referring to non-existent reports by “media on the island,” the report said the public found the exercises “overbearing.” With a provocative direct quote not in fact appearing in Taiwan’s media, it said: “Once this precedent is set, will such ‘calls to arms' be introduced in the future into high schools and junior high schools? 'Is Taiwan already at the stage where all the people of Taiwan are soldiers?’"

In fact, the Chinese Press piece was sourced to “Jun Zhengping Studio” (钧正平工作室), a social media account run by the Propaganda Bureau of the Political Work Department under China’s Central Military Commission (CMC). The pen name “Jun Zhengping,” which is a homonym of “military political commentary” (军政评) is regularly used in China’s party-state media for commentaries representing the CMC. The piece was also run by such outlets as the official Beijing Daily, and Shanghai’s Guancha website, known for its strongly nationalist, pro-government stance.

Founded by businessman Crescent Chau (周锦兴) in 1981, Chinese Press is known for its stridently pro-PRC editorial slant. In an interview with Chinese state-run newspaper the People’s Daily, Chau said his Montreal-based publication was locked in a “war” with Falun Gong (法輪功), a religious movement whose followers have been persecuted in China since the 1990s.

GOING GLOBAL

Telling Zhejiang’s Story

International communications centers, or ICCs, are sprouting up all over China. These centers, a crucial piece in the leadership’s bid to remake its external propaganda matrix, have opened in nearly every province and dozens of cities nationwide. Their spread has been expansive — but far from even. One province, coastal Zhejiang, now hosts 16 “local international communication centers” (地方国际传播中心) at the municipal level or lower — five times the national average.

Zhejiang is one of China’s wealthiest provinces, but this alone cannot account for its surge in new ICCs. Even wealthier provinces, like neighboring Jiangsu and Fujian, have not experienced similar growth. So why has Zhejiang become home to so many ICCs?

The answer defies easy explanation. It is likely a combination of various factors: more funds, more extensive overseas connections — and perhaps even the fact that Xi Jinping spent three and a half years as a top leader in the province. Whatever the balance of these factors may be, they are a reminder that even in China’s push for greater global influence, it continues to be local conditions and opportunities that matter the most.

Read our full piece on Zhejiang’s ICC boom to unpack this mystery.

The French Connection

Looking at state media reports on the spread of China’s international communication centers — now numbering over 70, according to our research — one would be forgiven for thinking that the initiative has been a roaring success. But a recent report from Young Journalists Magazine (青年记者杂志), drawing on interviews with ICC staff, points to problems in the system less than three years since it picked up pace.

These include a shortage of foreign talents and a lack of commercially viable products. Even cosmopolitan Shanghai has struggled to fill positions for its ICC, where staff blamed the costs and difficulties in processing visas and other paperwork for foreigners. “After the pandemic,” an employee told the Young Journalist, “there has been a huge loss in overseas talents, and everyone's difficulties are similar." As for the business model, the report said ICCs were at the mercy of subsidies from their local propaganda departments, unable to generate revenue from content that is produced without reference to audience demand.

Some ICCs, though, are squaring up to these challenges with ever greater ambition. Last week, Guangxi’s ICC announced plans to establish ten branches around the world, recruiting 30 foreign creatives and technicians to win hearts and minds abroad. At the same time, the ICC for Jinan in Shandong opened an overseas branch in Paris and another in Brittany, aiming “to innovate international communication methods,” and “strengthen cultural exchanges.” History buffs may recall a special connection between France and Shandong province: Most of the Chinese Labor Corps recruits who dug trenches for the Allies in WWI came from Shandong. Thousands stayed in France, forming the nucleus of later Chinese communities in Paris.

Only time will tell if these ICC branches are flashes in the pan or the start of a new, globe-spanning trend — bringing PRC propaganda centers to a neighborhood near you.

Collaboration in Cambodia

These are busy times for Guangxi’s international communication center. On November 30, the region’s ICC signed a new cooperation agreement with eight Cambodian media outlets, pledging to enhance “resource sharing, exchanges, and technological innovation.” The deal got the official seal of approval from both sides, with Guangxi’s minister for propaganda and the head of Cambodia’s Department of Film, News, and TV present at the signing ceremony.

The eight Cambodian outlets are not the country’s most important ones, though. One, Angkor News (吴哥新闻) has a measly 13,000 followers on Facebook. Others seem to be either fresh digital media startups or longer-established outlets serving Cambodians of Chinese ancestry.

This is all in a day’s work for the Guangxi ICC. Alongside neighboring Yunnan, they have been tasked with strengthening China’s external propaganda efforts in Southeast Asia — part of a wider campaign to leverage local expertise and make provincial ICCs spearhead overseas messaging. In January this year, Yunnan’s International Communication Center for South and Southeast Asia (云南省南亚东南亚区域国际传播中心) launched a new media network aimed at building “dialogue and practical cooperation” between media in Vietnam, Laos, and Vietnam. Back in March, we also wrote about Khmer, a bilingual magazine printed by Yunnan’s ICC and distributed in Cambodia to promote the benefits of Cambodia’s relationship with China.