Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 22 Mar

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

This year marks important anniversaries for both Taiwan and Hong Kong. Ten years ago this week, the Sunflower Movement saw students occupy the Taiwanese legislature for weeks to oppose closer ties with China, while in September of the same year, the Umbrella Movement saw mass street occupations in Hong Kong to demand a meaningful say in their government.

The Sunflower anniversary has, of course, been one of the biggest stories in Taiwanese media this week, with many identifying it as the moment everything changed: when the country’s seemingly inevitable absorption into the People’s Republic of China halted and new possibilities were suddenly opened. The increasingly proud, confident, and outward-looking nation we know today is in many ways a product of the paths created by the Sunflower students.

As for the legacy of the Umbrella protestors, however, you need only look at the other big story of the week: the passage of Hong Kong’s homegrown national security law, Article 23. The reality of Hong Kong today is a stark and rather grim contrast to 2014, when it felt like people power might win the day and mass peaceful protest would finally give Hongkongers what they had been denied for generations under British and Chinese rule — the chance to choose their own leaders.

Similarly, the downward spiral of desperate and sometimes violent unrest met with unrelenting crackdowns and ever-dwindling freedoms in Hong Kong is also a legacy of decisions that were made back in 2014. Thinking about “what could’ve been” isn’t particularly helpful, but remembering the poor and callous decisions that brought us to this point is an important part of setting the record straight, holding decision-makers to account, and not letting the latest official narrative win the day.

And on that note, happy reading!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

Cracking on with the Crackdown

This Saturday, a sweeping new security law, known locally as Article 23, comes into force in Hong Kong. Coming less than four years after the national security law imposed by Beijing, the 212-page law will broaden the scope of national security offenses and make these punishable by life imprisonment.

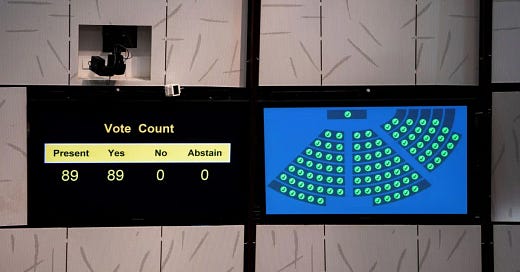

The morning after the law was passed by Hong Kong’s Legislative Council on Tuesday night, the People’s Daily dedicated its entire fourth page to the story. If that sounds like state media somehow knew ahead of time how the vote would go, you might be on to something: official broadcaster CCTV jumped the gun and reported on the law’s passage before it even went to a vote. To be fair, this wasn’t a hard prediction to make, since opposition politicians (if not already jailed) have been barred from the legislative process. In a scene likened by many on social media to China’s rubber-stamp NPC, the law was passed unanimously.

The law is the “manifestation of mainstream public opinion in Hong Kong,” the Party mouthpiece confidently asserted in its spread, citing the 98.6 percent positive feedback the government says it received among 13,489 responses from the public during its consultation period.

The list of important contextual factors they do not mention, however, is extensive: the unprecedentedly short consultation period; the pervasive atmosphere of fear, drummed up by state media, that has left critics afraid to speak out; the landslide victory achieved by pro-democracy candidates in Hong Kong’s last free and fair election, shattering the myth of a “silent majority” that supports the government; the reforms after that election that have barred all but the most unwavering government supporters from office; the survey results released just after Article 23 was pushed through revealing record low approval ratings for leader John Lee.

The Beginning and the End

People’s Daily also repeats several of the narratives dished out 24/7 by Hong Kong’s local state media and its “patriots-only” legislators to justify why the law is necessary and why it was necessary to rush it through in a record-shattering 11 days. Chief among these, particularly for audiences in Hong Kong itself, is that more national security legislation is needed for Hong Kong to dig itself out of the economic hole that it slipped into with the first round of national security legislation in 2020. This is encapsulated in the phrase used to market the law locally: “from order to prosperity” (由治及興). As Hong Kong lawmakers lined up to offer full-throated support for the law during Tuesday’s “debate” in the chamber, all without exception said that it would enable the government to finally focus on economic development.

There is a danger to this line should it fail to deliver immediate growth. Something similar has already happened with the city’s local councils, which residents were told would be laser-focused on livelihood issues after democrats were expelled from their ranks — only to devote their attention to flashy, expensive displays for tourists instead. In their mixed metaphors, Hong Kong’s patriotic forces have already accounted for this distinct possibility, referring to Article 23 as both “the final step” (much like the gutting of local elections was branded “the final piece of the puzzle”) and “just the beginning.” Which is it? A Schrödinger’s crackdown, it is both at the same time.

And one section of the People’s Daily spread may have made a Freudian slip when it quoted Deng Xiaoping’s famous assurance that the “horses will still run, stocks will still sizzle and dancers will still dance” (馬照跑,股照炒,舞照跳) in Hong Kong after its handover to China.

In Hong Kong itself, this line is seen as the epitome of Beijing’s shallow understanding of the city and its haughty dismissiveness of Hongkongers’ aspirations for anything beyond consumption and entertainment. Its unironic use here shows how little has changed in the CCP’s thinking in the four decades since it was first uttered. Interestingly, however, the People’s Daily decided to abridge the quote in this instance to simply “the horses will still run and dancers will still dance” — a tacit recognition, perhaps, of the fact the city’s stock market has been in free fall since the start of the national security crackdown and is unlikely to reverse course soon.

TRACKING CONTROL

Chronic Obstruction

When push comes to shove in China, it is the powerful state-run news networks that get to dominate the story, with the blessing of the country’s leaders. But a case last week of real-life pushing and shoving involving the country’s official broadcaster, China Central Television, stirred uncharacteristic questions about the role of journalists and their relationship to the public — and what rights they should and do have.

The scene unfolded as a news reporter from CCTV, the chief state broadcaster under the party-run China Media Group (CMG), and her filming crew were hustled away from the scene of a deadly gas explosion about 50 kilometers east of Beijing. Video of the live broadcast on CCTV-2 shows the reporter, clearly holding a microphone labeled “CCTV,” speaking calmly from outside the scene of the explosion when she is suddenly surrounded by uniformed personnel who block the camera and interrupt the broadcast. As the live broadcast cuts back to the studio in Beijing, the anchors are clearly caught off guard, a scene that would be jarringly unusual to Chinese television audiences.

As the clip made the rounds on social media, it drew anger from some, who criticized the actions of the local authorities. But as David Bandurski writes, a closer look at the case reveals a disquieting truth — that such acts of obstruction are not an exception in China, but the very nature of media policy.

For more on the story, you can also read CMP’s comments in The Guardian, France’s RFI Chinese and Le Monde, and Voice of America.

ON THE RECORD

A Decade of Sunflowers

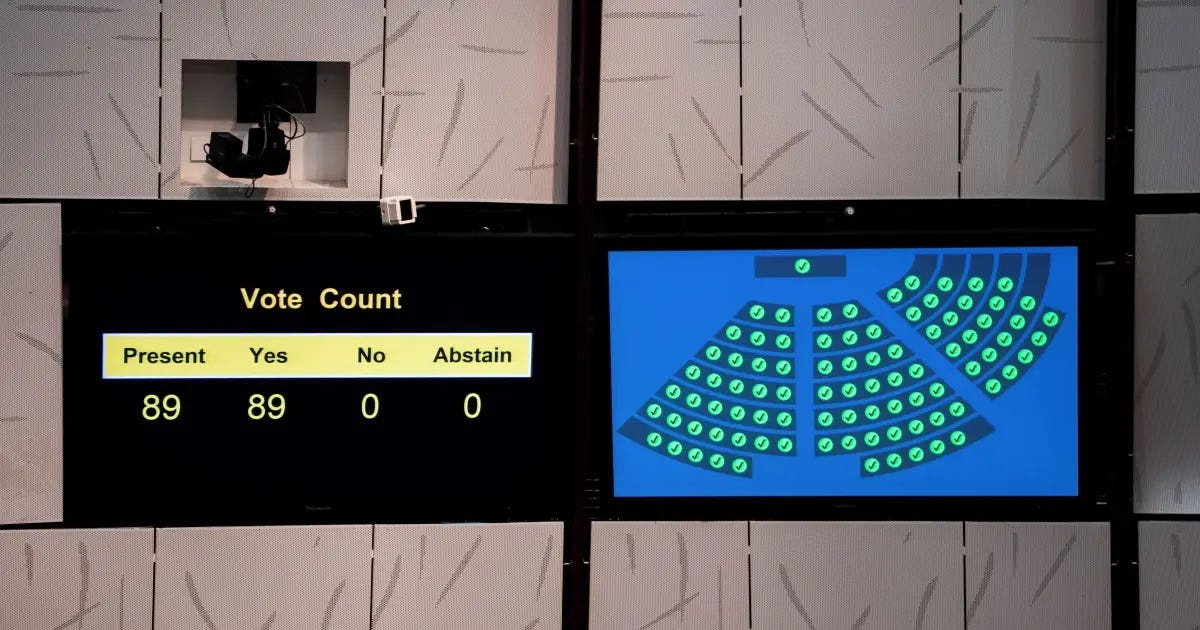

Ten years ago this week, demonstrators stormed and occupied Taiwan’s legislature for the first time in the young democracy’s history. The student-led Sunflower Movement (太陽花學運) stayed in the chamber for just over three weeks to oppose a new trade deal with China that was rammed through the Legislative Yuan by the then-ruling Kuomintang (國民黨), and which many feared would leave the country wide-open to Beijing’s influence.

Naturally, the movement was front-page news in Taiwan at the time, with the country’s (in)famously partisan news outlets staking out positions on its causes and protestors’ actions. “Pan-blue” dailies aligned witht he Kuomintang and in favor of closer ties with China, like the United Daily News (聯合日報)and China Times (中國時報), often criticised the student activists and portrayed them as a violent mob. To this day, UDN continues to blame the Sunflower Movement for tense relations betwen Beijing and Taipei, writing “after the Sunflower Student Movement in 2014, official communication channels between both two sides of the Taiwan Strait have been interrupted.”

Sometimes, though, these papers did adopt a more nuanced approach. In April 2014, for instance, the China Times challenged critics of the movement who attributed solely to the phenomenon of "angry youth" (憤青), laying out some of the underlying social and political issues that fueled the unrest.

Seeds of Change

Generally, the most sympathetic coverage of the movement could be expected from outlets associated with the “pan-Green” political camp championed by the now-ruling Democratic Progressive Party (民進黨). But the biggest of the Green dailies, the Liberty Times (自由時報), maintained a relatively neutral stance in its reports at the start of 2014. Some articles simply outlined the movement's demands while others highlighted the broad support it garnered from the public.

One of the movement’s most vociferous critics was CTi News, a TV station owned by the Want Want China Times media group. The station openly opposed and ridiculed the movement and its participants, making sexually suggestive comments about female activists on air, prompting a public backlash that led to complaints to the National Communications Commission (NCC) for violations of decency standards. CTi lost its terrestrial broadcast license in 2020 after a probe into its inaccurate and biased reporting.

Looking back, the Sunflower Movement was a turning point for Taiwanese media as well as its political scene. Just as a new generation of politicians and political parties came out of its aftermath, so too did independent digital news sources like The News Lens (關鍵評論網) and Storm Media (風傳媒), driven by young, often volunteer-based teams with limited resources. A decade later, it’s difficult to image either sector of society without the contributions of what’s become known as the Sunflower Generation.

SPOTLIGHT

Keywords for Change

Some of the most thoughtful reporting on the 10th anniversary of Sunflower Student Movement, which unfolded in Taiwan's Legislative Yuan in March and April 2014, can be found in The Reporter (報導者). In a series of reports this month, the outlet broadly explores the impact of the movement on Taiwanese society and politics today. It includes a scrolly-told timeline of the key events, and even a special multimedia page that takes readers back to the scene of the occupation of the Executive Yuan.

But if you read nothing else, check out the wonderful compilation of 10 keywords (關鍵字) at The Reporter that help to suss out the "complex causes and the manifold effects" of the movement — which the outlet put together with the help of scholars and other experts.

Inter-Generational Recollections

Another outlet to distinguish itself with it super reporting, storytelling, and design, is the Singapore-based (but very global) Chinese-language outlet Initium (端傳媒). This Sunflower Student Movement timeline that opens the series, which can be found here, is an immersive visual and auditory experience, winding back to the passage of the the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA) that planted the seeds of student opposition.

One article, “For Better or Worse, This is Me Now” (無論好壞,都構成現在的我), revisits five sunflower participants and explores their lives today, and the lingering impact of the movement. There are also recollections from a range of young people from all walks of life. The Initium series is at once recollective and alive. The editors write:

A decade has passed, and those who participated in the movement now have completely different experiences, each of them going on to lead different lives. Taiwan's political landscape has been reorganized and reshuffled in the aftermath of the Sunflower Movement, and civil society has emerged, thrived, and moved forward . . . If memory is limited, what do you carry with you after 10 years? If memories cannot be erased, how can participants hold them close?

This is journalism at its best. Engaging, deeply reported, and packing a sensory punch.

IN THE NEWS

China Stands Up for Free Speech — in America

With the United States poised to force China’s ByteDance to divest ownership of TikTok, a new champion of free speech and open markets has emerged on the global stage: the People’s Republic of China. That is, of course, according to the country’s tightly controlled media.

The targeting of the Chinese-owned platform is “bullying behavior” according to the propaganda department-run Guangming Daily. A specially produced report from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, meanwhile, enumerates the myriad ways the “United States regards freedom of speech as the foundation of the country but treads on it under the feet of political reality.” For them, the campaign to ban TikTok is just the latest example.

This report provided fodder for internationally-facing state media like the Global Times, China Daily, and CGTN, who presented the issue as black and white. US lawmakers — despite the radical differences between Republicans and Democrats — are seen as a single entity united in their distrust of the platform and motivated solely by selfishness. The articles uniformly cite the MOFA report as their only source, presented without expert comment or any unique angle.

Domestic-focused media took a slightly less top-down approach. Both CCTV and Hong Kong’s Wen Wei Po wrote about how TikTok had benefited the businesses and social lives of ordinary Americans, while providing scant details as to why US politicians are concerned about the app’s relationship with Beijing. A few cursory lines about the case against TikTok are quickly refuted by a statement from the company dismissing its detractors.

Compare this to sociologist Shaomin Li’s op-ed for the Detroit Free Press on March 19, with its detailed discussion of the relationship between the state and private business in China. For a Chinese outlet to even relate to readers the exact nature of US lawmaker’s allegations — how “public-private collusion in data-sharing is common in China” and that it is a matter of “business survival” for ByteDance to obey officials’ demands — would be dangerous territory.

Declaring American free speech a facade is old hat for the Communist Party — a tradition going back to at least the 1950s. But the complexities of the TikTok debate in the US, with various social and political groups vocally for or against the proposed bill — at times, indeed, with a heavy dose of nonsense and hawkishness — is only possible because of this freedom. The uniform stance of Chinese media is only possible where there is none.

CMP SHOWCASE

That Time TikTok's Founder Groveled to the CCP

Earlier this month, lawmakers in the United States passed a bill that would mean a nationwide ban of TikTok if ByteDance, its parent company, does not sell its stake within six months. The legislation, which casts the popular social media platform as a threat to national security, now moves on to the US Senate, where its passage is by no means assured — but where support for action against TikTok is coming from strong voices like Virginian Democratic Senator Mark Warner.

Some international media this week have asked to what extent TikTok is actually Chinese? The company, after all, was incorporated in California in 2015, has never operated its app inside China, and has a Singaporean CEO. What evidence is there really that TikTok is under the thumb of the Chinese leadership?

CMP’s past research can help.

Six years ago, we made a nearly full translation of an abject letter of apology penned by ByteDance founder and CEO Zhang Yiming (张一鸣) to authorities and the leadership after another of his company’s services, Jinri Toutiao, was accused by state media of failing to adequately police its content. Zhang’s politically-laden mea culpa CEO cuts right through the questions, one of the clearest illustrations we have of the risks that arise from China’s control-obsessed political system.

Read our analysis on the CMP website.

SOURCE CODE

China’s Egyptian Son-in-Law

With the Two Sessions underway in Beijing, China’s International Communication Group, or CICG (中国外文局), held a seminar in Doha on developing China-Qatar ties. The event focused on enhancing media cooperation between China and the Arab world, helping the two to speak with a “common external voice” (共同对外发声) that can counter Western media’s “contradictions” (矛盾) and “double standards” (双重标准) — combative phrasing that was curiously omitted from the event’s English-language readout.

Attendees included a collection of Arab academics and publishers as well as representatives from both the PRC embassy and CICG, which directs the China Publishing Group (中国出版集团) and serves as the country’s official foreign language publishing group, operating under the guidance of the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department.

Among them was a certain Ahmed Elsaid, known in Chinese by both this name (transliterated as 艾哈迈德·赛义德) and Bai Xin (白鑫). Elsaid is a regular at Chinese-Arab media conferences like the one in Doha, and is frequently quoted in and interviewed by PRC state media — but despite the platform provided to him by these outlets, his name returns few results outside state media, and no results in English-language media. So, who is Ahmed Elsaid and what is his connection to China?

“You Could Say I’m Very Lucky”

According to his LinkedIn profile, Elsaid holds a doctorate from China’s Ningxia University. He is the founder of the Bayt Al Hikma Culture Group in Egypt (希克迈特文化集团), which sells everything from Chinese arts and crafts to books in translation. His company is also the official distributor of Xi Jinping’s signature tome The Governance of China (习近平谈治国理政) in Arabic.

In an interview with CPG, Elsaid said he is “China’s son-in-law” (我是中国的女婿) and has proved his filial devotion to the PRC by buying black-market face masks to donate to China during the Covid-19 pandemic. His company has also expressed eagerness to help “tell good stories” about Beijing’s actions in Xinjiang to Arab audiences who might otherwise sympathize with the mostly Muslim Uyghurs persecuted for, among other things, practicing their religion.

This loving relationship, however, also seems to have been a profitable one for Elsaid. When the People’s Daily profiled five big benefactors of Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) funding last year, there was Elsaid again. He told the Party mouthpiece his business struggled financially before the BRI came to its rescue. As he put it, “You could say I’m very lucky.” His company now helps connect publishing houses and media outlets in China with their counterparts in the Arab world, and teaches Chinese throughout the Middle East.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Complexities and Contradictions in China's Media and Digital Space

Fang Kecheng (方可成) is an assistant professor of journalism at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK). His research focuses on journalism practice, political communication, and digital media. Before joining academia, he was a political journalist at Southern Weekly (南方周末), one of China’s leading professional news outlets.

We asked him a few questions about the hidden complexities and internal contradictions of the PRC propaganda machine.

Lingua Sinica: Outsiders often see the PRC propaganda machine as a seamless monolith that speaks with one voice. What does that miss about the complexities and contradictions inherent in the system?

Fang Kecheng: China’s political system is never a monolith. There are central-local dynamics and different ministries might have different interests. The nation's propaganda apparatus is similarly complex and fraught with contradictions. For instance, while local governments might conceal scandals and propagate falsehoods, the central government may compel these local entities to acknowledge their errors, especially in response to widespread public indignation. This tension has surfaced on multiple occasions, such as in the aftermath of the recent Yanjiao explosion, where journalists from CMG faced forceful removal by local officials as they attempted to report from the scene. Another instance is the Xuzhou chained woman case [in 2022], where the local authorities issued several conflicting statements in response to mounting pressure.

LS: Somewhat counterintuitively, you’ve said that as controls on this system tighten, contradictions actually multiply. Can you explain how?

FKC: Successful propaganda needs to be creative because persuasion is never an easy job. However, the development of creativity needs space; it cannot flourish under restrictive controls. An example is that, during the first term of Xi, there were quite a number of impressive propaganda projects, such as the short videos produced by Studio on Fuxing Road (复兴路上工作室). However, such pioneering initiatives have dwindled during his subsequent terms. This decline could likely be attributed to a reluctance to explore novel and imaginative approaches to propaganda, given the increasingly stringent political climate.

Moreover, for propaganda to be compelling, it must be grounded in trustworthiness. Sixth Tone, which belongs to the state-owned Shanghai Media Group, is an example of how it could really tell China’s story well when it was given room to conduct quality reporting on people’s lives in China. Its content was once respected and relied upon by China observers. However, perceptions of its inadequacy in serving the propaganda agenda led to targeted attacks by nationalistic influencers. Consequently, the imposition of stricter controls has diminished its allure and credibility.

LS: One fairly clear contradiction is how the more Beijing emphasizes “telling China’s story well,” the less it effectively does so. Using examples of how the state has both succeeded and failed in deploying soft power, why do you think there seems to be such tone-deafness about what works abroad?

FKC: I think the answer also lies in the structure of the political system and the incentives of officials who operate the soft power campaigns. Is there any objective evaluation of the effectiveness of the campaigns among their target audiences, or is the primary objective merely to satisfy the expectations of higher-level authorities? The ironic thing is that the very top-down directive to effectively communicate China's narrative often results in a greater emphasis on the latter.

GOING GLOBAL

The Strike That Never Struck

Did you hear about the great general strike that swept the United States last year, smashing records and paralyzing the world’s biggest economy as close to half a million workers nationwide joined the picket line?

No? That’s probably because it never happened. But if you watched this AI-generated video from CGTN — the international arm of China’s state broadcaster — you may be wondering how you missed this historic event. The animated clip, posted on X (Twitter), blends disparate facts together in way typical of AI-generated content. It implies the footage is about a single strike involving 453,000 workers — but that number is closer to the total number of people who went on strike across the US over the course of the year (and even then is still 5,000 off the mark).

The video, part of CGTN’s “First Voice” series, also appeared on the network’s Spanish-language X account — but not on its European, Arabic, or Russian ones, suggesting it is aimed at audiences in the Americas.

In his government work report at this year’s Two Sessions, Premier Li Qiang made it clear that industries across China should be prepared to implement “AI+” (人工智能+) — that is, to apply this emerging technology to their respective lines of work. China’s attempts to win hearts and minds around the world is no exception.

Nor is it a one-off: CGTN uploaded a similar video to their website on March 18, this time using a (real) protest in Vergennes, Vermont as a hook to explain the US’s military-industrial complex. State media’s expansion into misleading AI-generated content is only in its infancy.

ANTI-SOCIAL LIST

Who Was the Woman Crying at Bao Zheng's Memorial?

Footage of a woman wailing on her knees before a memorial to a Song-dynasty official went viral on the Chinese internet last week. Despite popular demand for more information, a lack of any press follow-up has instead let rumors fill the void. The question of why she would be kneeling before the image of an official who lived almost a thousand years ago goes to the heart of present-day questions of corruption, malfeasance, and social justice.

Bao Zheng (包拯), the historical figure at the heart of this mystery, who can also be referred to as Lord Bao (包公) or Justice Bao (包青天), was famed for his honesty and upright ways following his death in the 11th-century. Bao Qingtian (as he has come to be popularly known) served as magistrate for the Song capital in present-day Kaifeng, Henan province. Bao initiated judicial reforms that let petitioners lodge complaints against corrupt local administrators — and for this reason his name has become a byword for justice and good governance.

Some nine and half centuries later, the unknown woman appealing to Bao at his memorial temple in Kaifeng is believed to be a petitioner herself, eager to present some grievance to a higher official who can help her seek justice — and what higher official than a celestial one?

But the highest appeal here may also be to the internet and social media.

From the 1990s through the 2000s, as a new generation of media programs like CCTV's "News Probe" (新闻调查) experimented with hard-hitting programming about current affairs, petitioners came to see media as a possible vehicle for justice — a new form of Justice Bao. The joke in media circles was that two lines would regularly snake outside the offices of CCTV, the national broadcaster. The first were petitioners bringing evidence of local malfeasance. The second were local officials hoping to press the network not to run damning investigative programs.

The attention our contemporary Kaifeng petitioner has since received on online social media platforms has already inspired her fellow petitioners to follow suit and go over the heads of all earthly authorities, filing their complaints directly to Justice Bao. One video shows a group prostate at the same spot. When news spread that the site had been closed for maintenance, it looked like authorities were desperate to prevent any more repeat demonstrations.

Official media have only carried news from the municipal Culture and Tourism Bureau, clarifying that the woman was not an actress, as some netizens initially suspected, but likely a pilgrim crying merely because she was ”deeply moved” by the site. They also emphasized that the temple that had been closed was in fact another with the same name in a different city.

But despite heavy speculation about the woman from netizens, her identity remains unknown. One Weibo user known as “Judicial corruption fighter abc” (司法腐败斗士abc) claimed she was the mystery woman, and that grievance was against a court in northeastern Liaoning province that did not handle a legal case she was involved in properly. Earlier posts by the user, whose account has now been disabled, accused other provincial and municipal courts of corruption, so it’s also plausible this account was run by a whistle-blower using the event to amplify her cause.

We’ve written before in CMP about how stricter regulation of local media by provincial authorities means even the most trifling of incidents can become a black box, leaving rumor and misdirection to fill the void where verifiable facts should be. It means those trying to seek redress or publicize injustice at the grassroots have an even harder time getting the word out.

DID YOU KNOW?

Powerful Pen Names

Dominating page two of the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper on Tuesday this week, with a jump to page six, was a massive article that waxed poetical about China’s achievements in progressing toward a “cyber power” (网络强国) — and marking the 10th anniversary of Xi Jinping first articulating the concept, which it called an “important thought” (重要思想).

“Our glorious party will always be capable of grasping the opportunities of the age, and standing courageously in the current of the times,” it began. It spoke of the “missed opportunity” of the Industrial Revolution for China, which remained behind the West and suffered as a result. This time, with the strength of Xi’s steady and enlightened leadership, China would stride ahead of the world.

The byline for this paean, with its self-dealing praise, was an author named “Xin Ping” (信平). Who could this enthusiastic student of China’s cyber policy be?

Total CAC

One pro tip for China watchers is to look closely at bylines in the official party-state media. If something is not clearly labeled as by “this paper’s reporter X,” or from Xinhua News Agency, but still has a byline, the key is to look at the end of the text for a bio of the author. If no such bio exists, you might have stumbled on an official pen name.

In this case “Xin Ping” is a pen name that means “Cyberspace Administration of China commentary,” comprising the characters for “information” (信) and “peace,” with the latter being a homonym of “commentary” (评). This would have been written by a writer’s group (写作组) at the CAC and then approved by its top leadership, after which it was placed in the People’s Daily.

For more on this uniquely Chinese phenomenon, see “Pen Names for Power Struggles.”