INTERSECTIONS | March 21, 2025

A rundown of issues, analysis, and must-read stories about marginalized communities in the Sinophone landscape.

Dear subscribers,

Welcome to Intersections, our monthly Lingua Sinica bulletin highlighting the stories of marginalized communities in the Chinese-language media space — from women’s issues and feminism to queer perspectives, the struggles of disabled people, and more.

In this edition, I delve into state media narratives on International Women’s Day earlier this month, and the legacy of China's "Feminist Five" activists — detained 10 years ago. Also, don’t miss the preview down below of our interview with journalist Chen Hung-Chin on sexual harassment in the media workplace in Taiwan. That full interview will post next week here at Lingua Sinica.

With that in mind, I’ll say again what I always say — that I’d love to make this a conversation. So please reach out, and take a moment with the poll below to help us learn what might most interest our readers as we consider expanding our offerings.

Dalia Parete

CMP Researcher

dalia@chinamediaproject.org

OFFICIAL FRAMES

The CCP’s POV on Women

On a day meant to commemorate women, state-run newspapers in China exhibited a different priority: President Xi Jinping's closing remarks to the annual Two Sessions political meetings. Women were notably absent.

As International Women’s Day dawned on March 8, CCP papers from the central down to the provincial and city levels ran virtually identical front pages about Xi Jinping’s speech — a consistent, male-centered leadership storyline. The same top headlines and exact same image are priority in the People’s Daily (right), provincial Shanxi Daily (left), and China Women’s News (center). By now, Intersections readers are used to seeing this prioritizing of CCP frames over the concerns of women in the China Women's News (中國婦女報), the official paper meant to speak directly to women in China. This, of course, is a function of how media politics works in China, as a means of enforcing leadership in a top-down fashion. But it is an important visual reminder of what Xi has said, echoing Mao Zedong, that the CCP rules all — Party, government, military, civilian, and academic: east, west, south, north, and center. Add to that list: women.

PRIORITY GAPS

Reinforcing Gender Roles

On International Women's Day, several activities held nationwide were more about patronizing women than celebrating their contributions.

As if the CCP’s centrality was not already clear enough, commemoration activities on International Women’s Day unfolded in China under the slogan: "Following the Party on a new journey; women making contributions in the New Era.” The program for the day included both in-person and online recruitment events in Beijing tailored to women. You’re right to ask — what exactly does tailored mean?

Of all the job fairs held on or before Women's Day, two in particular caught my eye. One was an employment expo promoting "mom-friendly jobs" (媽媽崗) with flexible accommodations for women juggling work and taking care of their children. This, of course, is the leadership’s renewed vision of women — as homemakers, pushing up the country’s falling birth rate. Another was the “Supporting ‘Her’ Employment” (助力'她'就業 ) job fair, held in central Hunan province and sponsored by the Municipal Women's Federation (市婦聯聯合), the local branch of the same All-China Women’s Federation that publishes China Women’s News. The job fair offered 3,350 positions, predominantly in caregiving — including domestic service workers, baby nurses, organization specialists, and eldercare providers. While presented as "opportunities for women," these roles reflect and reinforce gendered labor roles by channeling women exclusively into care work.

The "mom-friendly jobs" (媽媽崗) initiative has been around since the mid-2000s, with job portals dedicated to these gender-specific jobs. Last year, the CCP’s official People’s Daily (人民日報) published an article painting the program as thoughtful social policy only, failing to address the fact that it was women alone who were being asked to balance work and childcare. Instead of offering such special accommodations, would it not be preferable to tackle systemic problems like equal parental obligations or all-inclusive childcare services?

IN MOTION

The Power of Expression

A local art exhibit covered in Taiwan’s media sends the message that people with disabilities can’t be painted into a corner.

On March 12, the Tainan Care Center (臺南教養院) inaugurated its latest exhibition, “Love Without Borders” (愛吾礙-師生聯展). Running from March 12 to March 28 at the Jingliao Day Care Center (菁寮日間照顧中心), a local hub serving elderly and disabled residents in the southwestern Taiwanese city, the exhibition showcases the creative skills of both individuals with disabilities and the staff of the center through puzzle art, paintings, oil paintings, leather crafts, and calligraphy. The purpose of the exhibition, according to the organizers, is to “let the general public see the unlimited potential of people with disabilities."

In the exhibition, which was reported by several media outlets in Taiwan, two artists and residents of the Center, Wu Yu Kuan (吳昱寬) and Xue Yuan Jie (薛原傑), present their work. For both, creating art is a vital way to relax, self-express and reconnect with the present moment. Fellow resident and artist Chen Shou-dian (陳守典) showcases a painting of his hometown, Chiayi (below), with the area’s distinctive yellow fields of rapeseed.

Wu Hui-jun (吳慧君), director of the center, emphasized that the exhibition was a way of enacting the spirit of the UN’s Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, promoting cultural equality and participation. "This exhibition is not just a display of artworks but also a dialogue about love and possibilities,” said Wu.

Support our work at Intersections by becoming a paid Lingua Sinica subscriber. Those subscribing before the end of March can use this link to get 10 percent off a paid subscription. Thank you for your support!

HERSTORY

The Feminist Five: Ten Years On

On the eve of International Women's Day 10 years ago, in March 2015, five female activists were arrested in Beijing, Guangzhou, and Hangzhou. The actions began on March 6 that year when Wu Rongrong (武嶸嶸), Wei Tingting (韋婷婷), Wang Man (王曼), Zheng Churan (鄭楚然), also known as "Datu," and Li Tingting (李婷婷), also known as "Li Maizi" (李麥子), were detained without charges. The women, collectively known as the “Feminist Five” (女權五姐妹), were reportedly taken in because of planned activism corresponding to International Women’s Day, including the distribution of anti-sexual harassment stickers. But it was widely known that the women were targeted because they represented a growing community of feminist activists in China — and were perceived as a threat by the authorities.

By March 2015, the women already had a history going back several years of peaceful actions against gender discrimination and domestic violence. These included the 2012 "Occupy Men's Toilets" demonstrations in the southern city of Guangzhou and in the capital Beijing, during which demonstrators temporarily occupied men’s toilets to draw attention to the relative lack of proper facilities for women. Significantly, these actions received coverage at the time even from state-run media, including the Global Times and China Daily (though most reports were published in English only). Up to 2015, in fact, the Chinese media covered issues of women and gender in ways that seem surprising today. For example, in a 2012 report by China Consumer News about controversial pre-employment physical examinations for female civil servants, Wu Rongrong, then a gender equality specialist at the grassroots Beijing Yirenping Center (北京益仁平中心), argued that non-medical gynecological examinations could damage women's dignity and intensify their fear during job hunting. She emphasized that women have the right to keep information about their bodies private from others unless for personal healthcare purposes.

The detention of the “Feminist Five” was an unfortunate turning point for feminist activism in China and for coverage and public discussion of related issues. As the crackdown on feminist activism and Chinese civil society more broadly was underway in 2015, the only coverage in domestic media voiced support for repressive actions. A Chinese-language report from the Global Times defended the detention of the "Feminist Five" activists ahead of International Women's Day and dismissed Western criticism of the judicial process as unwarranted interference. The piece argued that "female rights in China are not a sensitive topic” while drawing a critical distinction between legitimate advocacy and what it called "unlawful rallies intended to upset social order" (用非法抗議來挑戰社會秩序) — demonstrating how the Party frames even peaceful protest as a threat to stability.

But the legacy of the “Feminist Five” remains strong, as they continue to participate in the Chinese feminist movement, often through online forums. The Feminist Five inspired a shift in Chinese activism, driving a more diverse and inclusive feminist movement. If you want to know more about the "Feminist Five," their activism, and what it means to be a feminist activist in China, here are three great interviews with Li Maizi on China’s feminist movement and her personal experiences:

"The Ten Years I've Experienced Since the 'Feminist Five'" — Matters, March 7, 2025

“From Bullied Youth to Feminist Activist, From Political Prisoner to Exile — I'm Still Doing What I Can” — Wainao, March 7, 2025

"Activists' Struggle as Space to Challenge Power Shrinks” — Dasheng (大聲), June 2025

MAKING WAVES

Queer Resistance and Resilience

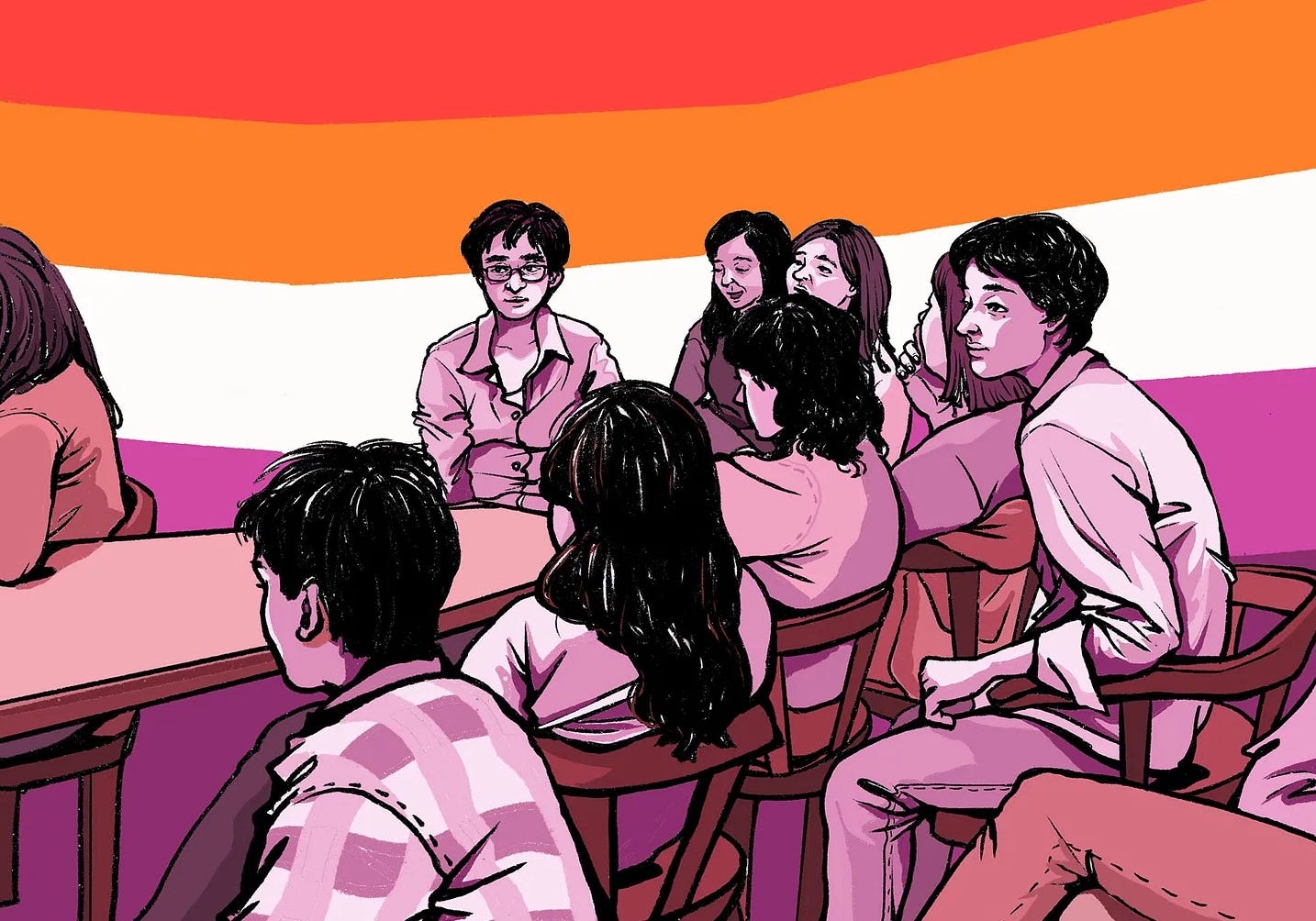

This month, the Chinese-language diaspora media outlet Mang Mang (莽莽) published a detailed historical account of the struggles of the LGBTQ+ community in China. The feature documents the challenges of building community in China against the backdrop of constant government crackdowns, surveillance and intimidation. The story draws on the experiences of a number of activists and scholars, including Yan Ying (嚴瀛), a grassroots lesbian activist from central China, and A Rou (阿柔), a feminist activist who worked to improve LGBTQ representation in Chinese media through the platform Queer Comrades (同志亦凡人) — a web-based interview program that invited both Chinese and foreign LGBT individuals to appear on camera to tell their stories.

For the queer community, the journey began in 1997 with decriminalization through abolishing "hooliganism" legislation (流氓罪) and 2001's declassification of homosexuality as a mental illness. By the late 1990s, gay and lesbian organizations in China carried out public advocacy, while periodicals like Sky (天空), and offline venues like Beijing’s famous Maple Bar (楓吧) and Chengdu’s Yuelianhua (月戀花), provided platforms for discussion and self-expression. The movement had even greater social impact between 2009 and 2014, and media platforms like Queer Comrades (同志亦凡人), which featured on-screen interviews with Chinese and foreign queer individuals, and Queer Lala Times (酷拉時報), played a key role in encouraging more positive LGBTQ+ representation in the mainstream media.

Things took a dramatic turn after 2014, as Xi Jinping’s administration led a broad crackdown on civil society groups. LGBTQ+ activists faced increasing pressure from the authorities, with the repression of activists like the Feminist Five (See HERSTORY above) in 2015 sending a chill through the community. From 2020 onward, many organizations and activities came to an end, including Shanghai Pride (上海驕傲節) and the Beijing LGBT Center (北京同志中心).

But as Mang Mang’s story makes clear, resistance and activism persist in China despite these pressures. As activist Cui Qi (崔旗) tells the outlet, agency can take shape in more decentralized ways: “Movements don’t necessarily have to rely on organizations or frontline activists,” he said. “Perhaps under these new environmental pressures, we will see a new situation emerge in which every member of the LGBT community takes responsibility for expressing gender diversity and LGBT equality.”

WHAT DOES IT MEAN?

Women's Fist-ism (女拳)

A derogatory internet slang term used to delegitimize feminist discourse by portraying women's rights advocates as misandrists.

"Women's Fist-ism," or nǚ quán (女拳) is internet slang that originated on Chinese social media as a wordplay on "women's rights," or nǚ quán zhǔ yì (女權主義). The term cleverly — and mean-spiritedly — incorporates the character for "fist" or "boxing,” quán (拳), characterizing feminists as aggressive extremists.

The term first gained academic attention in a 2020 article from Tsinghua University's School of Journalism and Communication, which looked carefully at the term’s problematic and derogatory nature. By 2021, the magazine Motherland (祖國雜誌), a bimonthly publication with nationalist leanings, adopted the term in an article that characterized feminists with what it felt were more extreme views — such as blaming their personal setbacks on men — as engaging in "Women's Fist-ism" as "hostile toward men" (敵視男性) and aspiring ultimately to "return to a matriarchal society" (回到母系社會).

The phrase went viral in April 2022 following controversy over a Chinese Communist Youth League (共青團) Weibo post celebrating male contributions to nation-building while overlooking women's roles. After female users criticized the post, Beijing Evening News (北京晚報), a newspaper under the municipal propaganda department, ran a commentary condemning these critics as practitioners of "extreme feminism" (極端女權) and "Women's Fist-ism" who were "stirring up trouble" (興風作浪).

The goal of the linguistic framing achieved by this derogatory term is to relabel women advocating for equality as simply attacking men. It creates a distorted narrative of feminism, reducing substantive gender equality discussions to stereotypical emotional outbursts — a rhetorical strategy that undermines legitimate discourse on women's rights in China.

THE EXPERT VOICE

Chen Hung-Chin (陳虹瑾)

This month, Heng Yu Chien, the editor of our Chinese-language outlet Tian Jian (田間) sat down with Chen Hung-Chin (陳虹瑾), the chief writer for Mirror Media (鏡週刊). Chen, who is also the co-author of an award-nominated investigative series on sexual crimes, shared her own experience with sexual harassment in the media workplace.

A preview of Chen’s interview follows. Stay tuned to Lingua Sinica for the full version next week.

Tian Jian: Have journalists and media played the role they need to play in the MeToo movement?

Chen: I believe there will be some changes, and of course, there will also be consequences to bear [for women] — and even some backlash and blowback. For example, in the US or Korea, after the MeToo movement, some male managers completely cut off promotion opportunities for female middle managers or refused to travel with female managers, thinking "If I don't interact with you, there won't be harassment" — which is actually a setback for gender equality.

As for whether the media has played its role and achieved the expected effect, I think it [reporting on the issue] will make potential perpetrators aware that they might have to pay a price, and that price might affect their work. I think potential harassers are now aware that their actions will have consequences.

I've written several reports on the MeToo movement and found that many patterns are eerily familiar. You speak out, and then you receive a summons. I was actually sued, went to court, and then the case was dropped. But few people know that after the case is dismissed, it's not over because the other party can appeal the dismissal.

In the long run, it's not a clean, decisive resolution. I think we're currently experiencing growing pains.

Tian Jian: Has speaking out impacted your career?

Chen: I think it will have some impact, though perhaps not so directly. When I was younger, reporting harassment wasn't even an option for me, because I was so concerned about how it might affect my work. Now, people understand what kind of person I am, and they take that into consideration.

After I took a clear stance, these incidents became less frequent. Some of my male colleagues would jokingly say to one another, hey, didn’t you see what happened before to that harasser? They would joke around like that [making light of a serious situation]. But for me personally, it removed a great deal of trouble.