INTERSECTIONS/ January 24, 2025

A rundown of issues, analysis, and must-read stories about marginalized communities in the Sinophone landscape.

Dear subscribers,

Welcome to the eighth edition of Intersections — our monthly Lingua Sinica bulletin highlighting the stories of marginalized communities in the Chinese-language media space: from women’s issues and feminism to queer perspectives, the struggles of disabled people, and much more.

This month, I delve as usual into the official voices projected through China Women’s News, but find a refreshing morsel of substance on the online “sheconomy.” What’s that? Well, read on. There are also stories about warnings from the government not to discuss “gender rivalry” over the Spring Festival holiday and a great series from The Reporter about LGBTQ+ people in Taiwan.

I’ll say again what I always say — I’d love to make this a conversation, so please reach out. We want to hear about new outlets, stories, perspectives, or contributions from any of you. While we’ve focussed primarily on women’s issues in past bulletins, we hope that Intersections can truly live up to its name and cover all groups and individuals facing discrimination. If we’re skipping over something you think demands our attention, we want to hear about it!

I wish everyone a happy Lunar New Year!

Dalia Parete

CMP Researcher

dalia@chinamediaproject.org

OFFICIAL FRAMING

The CCP’s POV on women

Founded in 1984, China Women's News (中国妇女报) is the official newspaper of the All-China Women's Federation (ACWF), China’s official women’s rights organization. The newspaper aims to “sensitize society to women and women to society, advocate gender equality, and promote women's progress and development.” But the paper’s propaganda role often takes center stage. Each month, I survey the paper’s front page to see what this mission looks like in practice.

First, my monthly rundown of front-page coverage:

Above the Fold

Looking at a week’s worth of the China Women’s News front pages from January 16 to January 23, it’s clear that more general and government news supersedes women’s issues. As usual, articles on women, their stories, and relevant governmental policies rarely make it to A1.

Most headlines this month were devoted to Xi Jinping’s various phone calls and meetings with foreign leaders or meetings of the all-powerful Politburo of the CCP Central Committee.

In most cases, as the above examples show, reporting from official media on women includes little of real relevance at all to women. But from time to time there are modest but notable surprises. Above the fold on January 18, there was a fascinating story detailing how women in live streaming services can be empowered by their work, creating new economic opportunities for themselves as part of the burgeoning tajingji (她经济) — a direct translation of the English “sheconomy“ that captures the spirit of the trend, if not the wordplay.

Xinhua News Agency (新华社) already noted this trend in 2023 but not how online retail broadcasting fit in.

The China Women’s News article talks about how a nationwide initiative sponsored by local women's federations has helped women start careers in live video shopping. These groups claim to have helped women generate income by selling local produce — lining their pockets while promoting local products and culture. Some examples include live-streaming events in Gansu and Guangxi that saw women hawk regional delicacies such as mangoes and plums. In one instance, the article boasts, women managed to sell over three and a half tons of mango.

The piece differs from the usual China Women's News fare in that it focuses more on the story’s individual subjects than the role played by official benefactors. It may, however, be overselling the positive effects of the digital “sheconomy” — a paper published in the Journal of Chinese Sociology last year found that, while rural women engaged in e-commerce could boost their incomes, they failed to see more sustained benefits like financial security or career success.

PRIORITY GAPS

Harmonizing the Holidays

As anyone steeling up to face family over the Lunar New Year knows well, sidestepping questions about marriage and children can be an impossible dance. But if you’re posting online in China over the holiday, broaching these subjects could land you in trouble with censors.

“No marriage, no children” (不婚不育) is one of the prime targets of the latest internet cleanup launched by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC). As the country’s population declines for the third year in a row, putting more pressure on an already slowing economy, authorities are intent on boosting marriage and fertility rates. Talk of preferring to stay single or live without children is even more likely to trigger the government than it is one’s parents.

Other terms in the CAC’s crosshairs include "radical feminist" (极端女权) and "gender rivalry" (性别对立). The former, as we’ve written before on CMP, is often used as derogatory slang for women brave enough to raise their voices and challenge the Party and dominant social mores. The latter is what you supposedly get whenever someone expresses a critical opinion contrary to official narratives, shattering the thin veneer of “harmony” imposed from above.

An odd look, you might say, for the Chinese Communist Party, normally so keen to boast of how their rule has elevated women to "hold up half the sky." But counterintuitive crackdowns are somewhat of a CAC specialty. In past campaigns, they have targeted “class rivalry” as well — that is, any content likely to stir up feelings about the widening gap between rich and poor.

Catch up with the latest edition of the Lingua Sinica newsletter to get the full rundown on the CAC’s Spring Festival internet crackdown.

#METOO

No More Shame

For women everywhere, the name Gisèle Pelicot hardly needs an introduction.

The French woman’s court battle against her husband and the 72 men he allowed to rape her over a period of nine years has both shocked and inspired the world. By choosing to go public with her identity, the ordeal she suffered, and her fight for justice, she demonstrated where the shame truly lay in instances of sexual abuse: not on the victims but on their abusers.

Taiwanese outlets have been following her story closely since the trial began. Here, media coverage has praised Gisele’s decision to keep legal proceedings open to the public so women going through similar experiences could no longer be shamed into silence. Her powerful statement that "it is not us who should feel shame but them" has been widely quoted in media across the political spectrum — for example in CommonWealth Magazine (天下雜誌), blue-leaning United Daily News (聯合報), and the green-leaning Liberty Times (自由時報).

News stories have consistently portrayed Pelicot as a figure of dignity and resilience. Taiwanese newspapers frequently refer to her husband as a "demon” (惡魔) and “heartless man” (狠心夫). CommonWealth Magazine also highlighted her decision to keep his surname, since she said her children and grandchildren would be proud of their connection to her story of courage. “I do not want them not to be ashamed to have the name,” she said. “I want them to be proud of their grandmother. I want people to remember Madame Pelicot, not Monsieur Pelicot.”

WHAT DOES THAT MEAN?

Tranny (人妖)

As awareness of gender identity has grown globally, the Chinese-speaking world has not been left out of the conversation. In many ways, Taiwan, famous for hosting Asia’s biggest Pride festivities and being the first Asian nation to legalize same-sex marriage, has been a leading voice for LGBTQ rights in the region. When transgender folks are discussed in the country, the accepted nomenclature is kuaxingbie (跨性別), literally to “cross genders.” A trans woman is a kuaxingbienüren (跨性別女人) or simply kuanü (跨女).

But in Chinese media, particularly across the Taiwan Strait in the mainland PRC, another, more offensive moniker lives on: renyao (人妖). Literally “human monster,” it is variously translated as “ladyboy” or “tranny.” The term is considered a slur according to modern sensibilities, directed at feminine-presenting people assigned male at birth. But it has a history that goes back to some of China’s earliest dynasties, and is threaded throughout the history of its modern media.

This age-old stigma even persists to the present day. When influencer Abbily shared the story of her transition online in 2021, messages of support were mixed with disdain from those who said she had a "disease." Recent stories also perpetuate harmful stereotypes; a blog post on Sohu last year about a trans woman who married a wealthy businessman made her an object of pity.

To find out more, check out the latest entry in our CMP Dictionary for renyao or “tranny.”

Thankfully, media coverage of LGBTQ+ people in Taiwan tends to be a bit more open-minded. At least, that’s the case with independent digital news outlet The Reporter (报道者), which last week published a series of articles profiling transgender youths and looking at how their families and friends have navigated their transition. It offers an intimate portrait of its subjects’ lives, giving readers a meaningful sense of what it means to be trans in Taiwan today.

Check out the series to see how media can be part of the solution rather than the problem.

FOOD FOR THOUGHT

Serving Up a Controversy

Another month, another row on Taiwanese social media. On December 26, a group of male students from an all-boys high school in the heart of Taipei drew more fire to the McDonald’s fast food chain — still reeling from the suicide days earlier of a female employee amid allegation of sexual abuse by her supervisor — after they posted a provocative photo in a local restaurant with the caption: “A world without women's rights is a good place”(沒有女權的世界真好).

The students, from Taipei Municipal Jianguo High School, faced a huge backlash for their message, insensitive at any time, but especially toxic amid the controversy already enveloping McDonald’s. According to media reports, the boys had been angered by calls for a boycott of McDonald’s, which had been fined by Taipei’s labor authorities for its failure to provide protections against sexual assault. As the controversy broiled, the school promptly issued an apology. "Students from our school posted inappropriate comments through a class Threads account on December 26th,” it read. “We hereby express our apologies to the public.”

The fallout from the story has opened up a broader discussion on the new generation’s attitudes toward women’s rights. A writer in the United Daily News argued that young people need to be better educated, especially when it comes to respecting women and girls and taking responsibility for one’s actions. Garden of Hope (勵馨基金會) — an NGO that helps women facing abuse, trafficking, and domestic violence — asked why Taiwan’s Gender Equity Education Act has failed to promote equality and prevent sexual assault 20 years since it was enacted.

IN MOTION

Not Your Usual Box Office Hit

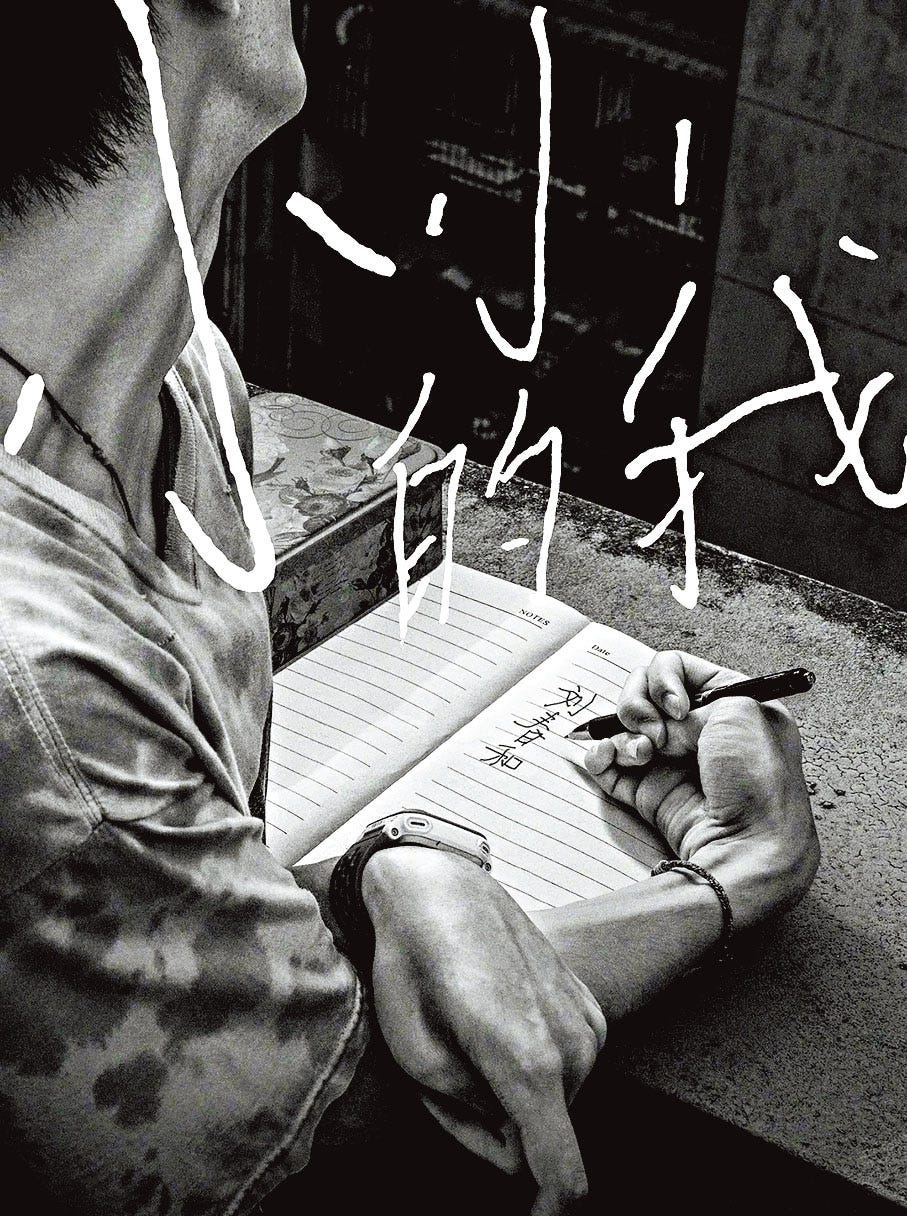

At the Tokyo Film Festival last November, Chinese director Yang Lina (楊荔鈉) unveiled her latest work, "Big World" (小小的我), which follows the story of Liu Chunhe (刘春和), a 20-year-old man living with cerebral palsy. The film, released in Chinese theaters on December 27, is in many ways a fresh portrayal of people with disabilities in China, where they have typically faced discrimination and a lack of opportunities. At points in the film, that discrimination is painfully on display, as when Chunhe’s grandmother suggests he might learn to play the drums, to which an elderly companion responds: “But you know, he is an invalid, so how can you expect him to play the drums?”

In various scenes, Chunhe is referred to with this word used by the elderly friend — canbingren (残病人), which bears the derogatory sense of "invalid" or “handicapped.” The word has largely fallen out of favor in China today, though offensive alternatives like canji (残疾), which vaguely references deformity, remain common. In Taiwan, where sensitivity to people with disabilities has kept pace with global norms, such terms have long fallen out of use. According to medical institutions in the country as well as to the National Human Rights Commission, the preferred term is "people with disabilities" (身心障礙者).

Through Chunhe’s story, “Big World” explores these lines in a fresh way, inviting the viewer to be aware of them and their effect on the main character. The film is infused with his humanity, and the ordinariness of his world often resonates. As viewers watch "Big World,” they inhabit the protagonist's day-to-day reality as he encounters setbacks and triumphs. He folds laundry, pursues romance, hunts for employment, and practices for his driver's test. Meanwhile, he is constantly made aware of the public perceptions that surround him. "In crowds, I've encountered all kinds of looks,” he says at one point, without judgment. “Some pity me, some fear me, and some are disgusted by me."

The Shanghai-based news outlet Guancha remarked on the film's emotional resonance, calling it an “unflinching portrayal.” In other films with disabled characters, the outlet said, “visually cruel things such as physical and mental defects and the inconveniences in life” were generally not shown. In another commentary on the film, the state-run Xinhua News Agency called “Big World” an "authentic representation" of the everyday lives of people with disabilities in China.

It may also speak to the power of the film that it has earned seven billion yuan — nearly 970 million dollars — at the box office since its release.