Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 14 Dec

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

Conference season is drawing to a close here in Taipei. The past two weeks have seen a flurry of events hosted by civil society organizations, including the China in the World summit, and a global Hong Kong studies conference at Academia Sinica. It feels like every academic, activist, researcher, and journalist in the space has been passing through for what I overheard one CITW attendee describe as “Woodstock for China-watchers.”

It may be a small world we inhabit, but being at the center of it has still felt, in turns, both exciting and exhausting. And with Taiwan’s national elections just a few weeks off, we won’t get much of a reprieve. With that in mind, we’ll take a break where we can. The Lingua Sinica newsletter will be taking a very brief holiday hiatus before returning to you in the new year, but keep an eye out in the meantime for other work from the China Media Project.

In this edition, we present a snapshot of the many big stories consuming Chinese-language media in the past two weeks and developments in the space: from Hong Kong’s District Council election to China’s framing of the crisis in Gaza, and, of course, the race for the presidency in Taiwan. One of the important stories we didn’t have time to cover ourselves was the passing of Gao Yaojie, a doctor and activist who blew the cover on China’s Aids epidemic, which was spread due to the practice of blood-selling in impoverished rural areas. Dasheng, who we will be speaking to in our next issue, uploaded this interview with Gao, which includes English subtitles.

Until next time, happy Christmas!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

IN THE NEWS

Hong Kong Hits a New Low

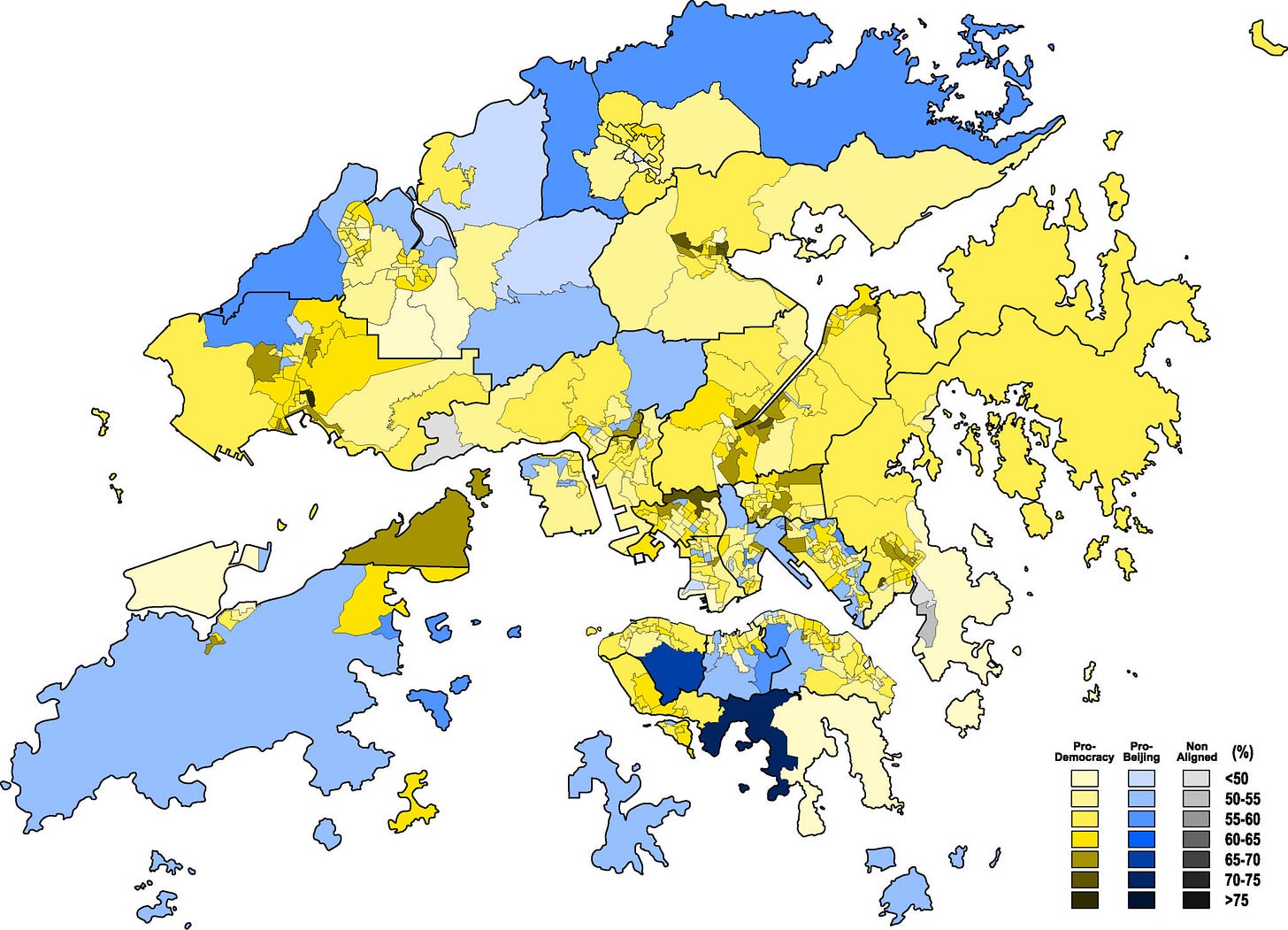

A record-low turnout at Hong Kong’s District Council elections on Sunday has prompted some interesting explanations from state-aligned media and government officials in the territory.

Chief Executive John Lee (李家超) — who previously stressed the importance of voter turnout — insisted that the 27 percent of electors who cast ballots was actually “good,” even if it was 44 percent lower than the last election in 2019. The chairman of the DAB, Hong Kong’s biggest pro-Beijing party and Sunday’s biggest winner, suggested turnout was so low because many Hongkongers were up north doing their other patriotic duty, supporting the mainland economy.

The state-owned Wen Wei Po said the vote “symbolizes the solid progress of Hong Kong's democratic structure.” In a tract that reads like it was pre-written and at no point addressed the historically low turnout, the election was hailed — bizarrely — as a “cultural feast” (文化盛宴) that “inspired the public to vote actively.” Fellow state-owned publication Ta Kung Pao, however, did dip its toes into official apologia, carrying comments by Chief Secretary Eric Chan (陳國基), Hong Kong’s second-in-command, who said that “voter turnout is not the most important thing; it's more important to elect the right district councilors.”

Outside Hong Kong itself, diaspora and exile media outfits have been less forgiving. The Points Media (枝角), an outlet founded earlier this year, called the poll a “political game” (政治遊戲) among the city’s biggest pro-Beijing parties. Taiwan-based Photon Media, reporting that most appointed District Councillors are also members of the Election Committee responsible for selecting the Chief Executive, wrote that elections in Hong Kong had become a system of “political rewards” (政治酬庸) for those who obediently serve the government.

To find out why Hong Kong’s district-level elections are so much more important than they seem, check out our “Did You Know?” section below.

MISDIRECTIVES

Pitting Gaza Against Xinjiang

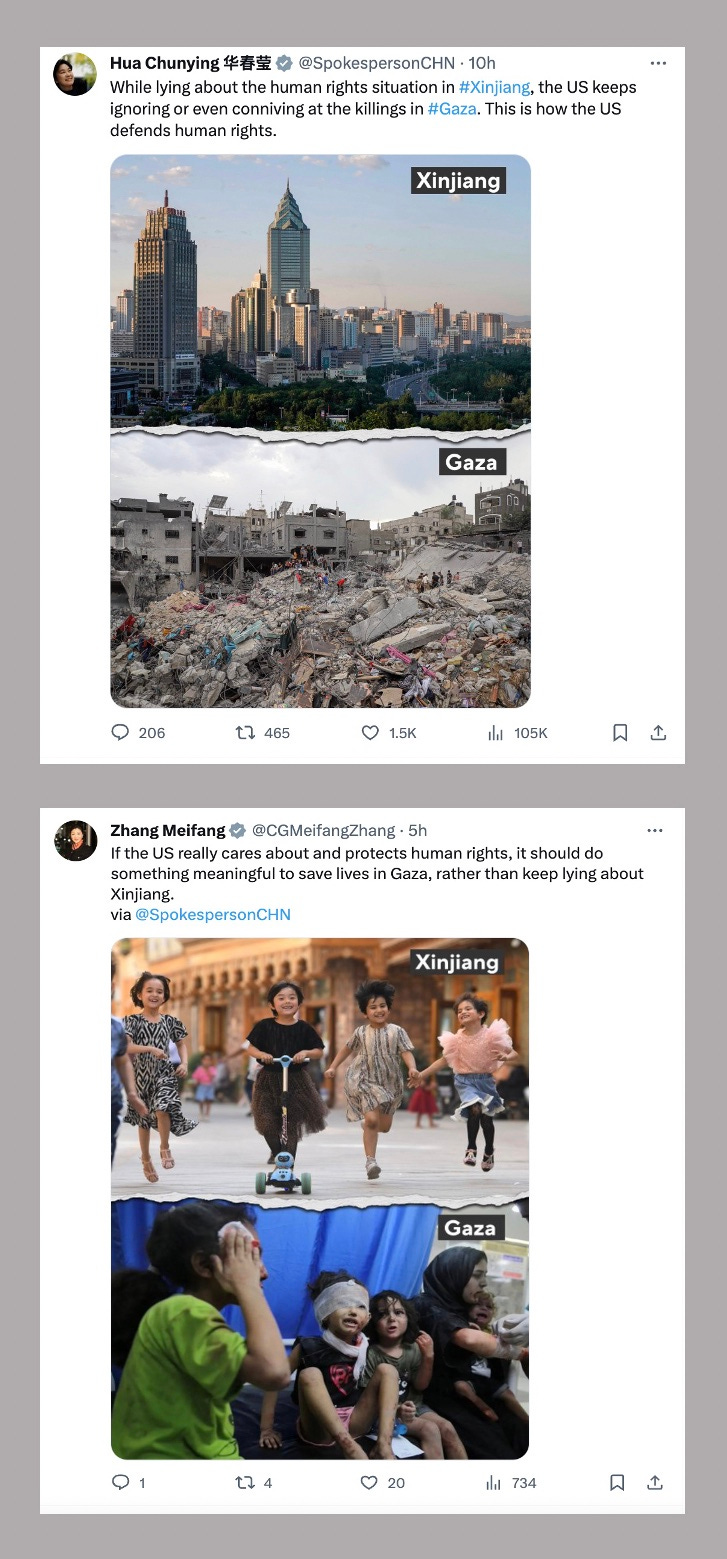

Amid a worsening humanitarian crisis in Gaza, as Israeli troops and Hamas fighters battled fiercely across the territory, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) and state-run media have found fertile ground for disinformation, holding up the role of the US in the crisis against glowing images of Xinjiang — where a report from the UN high commissioner for human rights (OHCHR) last year found credible evidence of serious human rights abuses against Uyghur Muslims that could amount to “crimes against humanity.”

On X (Twitter) this week, Zhang Meifang (张美芳), China's consul general in Belfast, wrote: “If the US really cares about and protects human rights, it should do something meaningful to save lives in Gaza, rather than keep lying about Xinjiang.” The post included contrasting images of Xinjiang and Gaza. In the Gaza image, children with bandaged wounds weep in a hospital; in the Xinjjiang image, children play joyfully in the streets.

Zhang, who has 157,000 followers on the platform, credited the image to Hua Chunying (华春莹), the outspoken “wolf warrior” spokesperson for the MFA, whose account (with 2.3 million followers) included another contrasting image of Xinjiang’s capital Urumqi glittering in the sun, against an image of the rubble of Gaza.

Soft Pitches from China’s Media

MFA drum-beating about Xinjiang and Gaza has driven a wave of coverage in the Chinese media this week striking back against accusations from the US and EU of serious human rights abuses in Xinjiang, following the release on December 8 of a related report from the US Department of State. News stories have almost uniformly drawn on remarks made on Monday by MFA spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) in response to a question planted by the government-run China Daily at a press conference.

Asked about the US report, Mao called it a “false narrative,” then threw up a smokescreen of whataboutism, drawing Gaza into the mix with US gun violence and drug abuse: “If the United States is genuinely concerned about human rights, it should effectively address the problems of racial discrimination, gun violence and drug abuse in its own country, and should not exclusively block the adoption of a Security Council resolution calling for a humanitarian ceasefire as the humanitarian disaster in Gaza worsens.”

ANTI-SOCIAL

Are you on LINE?

If you live in Taiwan, it’s hard not to be. It may not be an inescapable as the “everything app” WeChat in China, but the Japanese messaging app is far and away the most popular way to keep up with friends, family, and — increasingly — the news.

Among your private conservations and group chats, you can add public channels belonging to political parties and candidates and virtually every news outlet. When your phone buzzes with a push alert, it could be a colleague telling you about the next happy hour or your preferred presidential candidate reminding you about the next rally. It’s a very Taiwanese way to inject the “human touch” (人情味) into the political.

LINE itself also curates the news in LINE Today, a news hub available from the main menu you use to toggle between contacts. With more and more multimedia features, this messaging app has also become the most popular news source in the country. And with national elections just weeks away, they’ve launched an election zone section to minimize the reach of misinformation and to help users keep up with the deluge of information.

If you’re like us, however, you probably have so many politicians and media on your contact list that it’s impossible to stay afloat!

TRACKING CONTROL

Feeding Rumors by Fighting Them

In its latest action to rein in errant behavior on social media platforms in China, the country’s top internet control body announced last week that it had shut down 1,660 online accounts, alleging they had either disturbed social order or “fabricated public policies.”

As is typical of regulatory language on information in China, the notice couched the actions in metaphors of health and safety, urging the need to prevent the spread of fake information to “purify the online environment.” But a closer look at the cases cited by the CAC suggests a real public interest in issues such as safety, food security, regulatory overreach, and the rights of gig economy workers — and an appetite for related information that is not mediated and controlled by the Party-state.

So are the public opinion controls of the CCP actually fighting rumors, or are they in fact feeding them?

Find out in The Vicious Cycle of Rumor in China by CMP Director David Bandurski.

SPOTLIGHT

Falling Like Dominoes

Museums are facing a reckoning across Hong Kong. All at once, four different institutions are facing closure, relocation, or remodeling. At a time when China is aggressively pushing its political authority over the city and punishing dissenters, it’s no surprise many see the sudden changes as a full-on assault on local identity.

This week, Initium Media (端傳媒) published a special report reviewing the changes. The Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, housed in a British fort overlooking the strategic Lei Yue Mun Channel, is due to become the Hong Kong Museum of the War of Resistance and Coastal Defence, replacing exhibits on the Battle of Hong Kong and Japanese occupation with ones on the war against Japan in the Chinese mainland, led — according to official accounts — by the CCP.

Meanwhile, the beloved Science Museum will be booted out of central Tsim Sha Tsui and replaced with a museum dedicated to the achievements of the CCP. The museum will be relocated to faraway Sha Tin, where it will take over the current site of the Hong Kong Heritage Museum, which is dedicated to local history, art, and culture. It remains unclear if this will be the end of the Heritage Museum. Finally, the Hong Kong Museum of History’s permanent exhibition “Hong Kong Story,” closed since 2020, is due to reopen with what many fear with be a blinkered fixation on nationalist narratives.

Initium’s piece asks why museums have become such an important target of government attention. It borrows from the work of Benedict Anderson, who identified museums — together with censuses and maps — as the one of the three main institutions of power that “profoundly shape the way in which the colonial state imagines its dominion — the nature of the human beings it rules, the geography of its domain, and the legitimacy of its ancestry.” For regimes that do not seek legitimacy through the consent of the government, the past and how we see it matters tremendously. This is was true for the colonial authorities who first created these institutions, and it still is today.

Why Taiwanese Are Trying to Keep Out Indian Workers

Last week, protesters gathered in Taipei to demand the government cancel an agreement to welcome migrant workers from India. The country is already home to nearly 750,000 migrant workers from across Southeast Asia, but it’s been decades since the last time Taiwan took in laborers from a new country.

On the surface, it may seem like an open-and-shut case of xenophobia. Despite its well-earned progressive laurels on many other issues, racism colorism, and xenophobia are a reality in Taiwan. And with its own population shrinking, Taiwan is facing a labor shortage that cannot be met without foreign help — so why else keep them out?

That’s the question Taiwanese digital news outlet The Reporter tries to answer in its recent piece “After 20 Years, Why Has India Reignited the Controversy Over Discrimination Against Migrant Workers?”

Some organizers say the rights of migrant workers already in Taiwan need to advance before bringing in more, and they welcome more migrant workers from the countries Taiwan already has agreements with. They also say that the root of the problem is Taiwan’s criminally low wages — a dire problem the government has done little to solve. Instead of bringing in more low-cost labor, workers in Taiwan need to be paid more, they say.

The good intentions of those behind the protest, however, don’t erase the vitriol from others to which Indians in Taiwan have been exposed. Some say they no longer feel welcome or even safe in their adopted country. It’s a complex issue, but The Reporter does a characteristically nuanced and sympathetic job of communicating those complexities.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

The Alternate Ethics of Chinese Journalism

The following is just a taste of our recent interview with Emily Chua, an anthropologist with the National University of Singapore whose new book The Currency of Truth is based on years of fieldwork with journalists in Guangzhou and Beijing — and a fascinating exploration of how Chinese news workers construct an “alternate ethic” of journalism that challenges assumptions about the industry in the West. Read the full thing here.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick: At CMP we try to highlight the exceptional work of Chinese journalists and push back against the perception that there isn’t meaningful reporting being done in China. In your book, you warn that too much emphasis on journalistic excellence can lead to the motif of “pockets of exceptional journalists.” Why is this problematic and how do you push back against it?

Emily Chua: Anthropologists try to understand what things are like in the field we’re investigating, which we assume will be different from anywhere else. I think that’s a difference between a media studies or political science approach to journalism and an anthropological one. With political science, it’s very important to have a definition of journalism going in, but with anthropology we think that news is going to be a different thing in different places — it’s completely shaped by the context.

So when I went in, I wanted to do so with an openness to exploring what news meant for this institution and culture. If you go in and only look at people who are doing a very specific kind of journalism, then you’re going to be missing most of the picture. That’s why I set out to do an ethnography of non-heroic journalists.

RHK: You observe that even these “non-heroic” newsmakers, the so-called cogs in the system, also exercise agency in their daily work. What are some of the ways they do this?

EC: In the context of Chinese journalism, I was trying to push back against the way that agency tends to get conflated or even confused with something much more specific — basically, politically independent public speech. That’s a form of agency that’s closely associated with journalistic practices as we learn them. In Western contexts, that’s the whole purpose of journalism. But if your objective is to understand how news can be made and thought of and lived with differently in other places, then it’s important to broaden our sense of agency.

Keep reading “The Alternate Ethics of Chinese Journalism.”

DID YOU KNOW?

Why Hong Kong’s Local DC Elections Should Matter to International Media

Sunday’s District Council (DC) election in Hong Kong was the first after drastic overhauls since 2021 — branded as “improvements” by authorities — left the system of local representation almost unrecognizable. On its surface, the election of these minor local officials who oversee rubbish collection and bus-stop locations may not seem worthy of international news headlines, but to understand their true significance we need to take a trip through Hong Kong political history.

The DC’s predecessors were set up by British authorities in the 1960s and 70s, as a series of mass protests shook colonial rule, to mobilize support for their own policies and monitor the grassroots. They were tightly controlled by the government and open only to “responsible citizens” — code for good subjects. Initially, they only comprised appointed members and government officials, but in 1982 they also began to included an elected proportion that gradually increased until, around a decade later, they had become fully elected.

After Hong Kong’s handover in 1997, reforms to make the Legislative Council more representative were reversed, but DCs were left relatively unscathed, making them the only genuinely representative body in Hong Kong politics. As such, they became a barometer for the true political climate and an outlet for voters to back the camp they wanted to see wield actual legislative power (something decried as “politicization” in officialese). This dynamic climaxed in 2019 when, after months of mass protests failed to win concessions from the government, voters turned out in unprecedented numbers to deliver a landslide victory to the pro-democracy camp, which gained an absolute majority in votes and electoral seats across all 18 districts.

The “improvements” imposed after this humiliating defeat for the government have reduced elected seats in the Councils to a small minority and instituted a “patriots-only” screening process so intense that it weeded out not only all opposition candidates but even the more moderate pro-Beijing ones as well. The vast majority of those standing on Sunday, in fact, were also members of the committees responsible for nominating themselves.

It’s easy to see the gutting of the DCs as a simple, downward trajectory: a fall from the heights of Western democracy to the depths of Eastern despotism. But the long view of history reveals something even more tragic: DCs in 2023 are a lot like they were before 1982, organs of top-down control more than bottom-up representation, open only to “patriots” (or, as the British would say, “responsible citizens”).

The DC reforms have been billed as a part of “decolonization,” stripping away lingering British characteristics and replacing them with Chinese ones. Considering how DCs have come full circle, however, this “Sinicization” of local politics looks a lot more like re-”Britishization” — a return to colonial form.

NEWSPEAK

Stirring Up Controversy

Over the past few decades, references to “hyping” (炒作) in China’s official discourse have been central to attacks against negative reporting from international media that the CCP regards as a challenge to its political reputation and legitimacy. The term can also be used to broadly target critical discussion on the internet and social media inside China, linking such chatter to alleged foreign plots by nebulous “hostile forces.”

For anyone observing Chinese media coverage of international affairs in particular, accusations of hyping are never far behind. On December 4, 2023, alone, for example, one report accused “certain Western media [of] hyping Vietnam distancing itself from China,” while another said Western media had “hyped the issue of Chinese military support for Russia,” and yet another said Western media had hyped China’s plans to invade Taiwan between 2027 and 2035.

The bottom line? On any issue the CCP regards as being of strategic importance, the Party itself gets to decide what is factual — and anything less or more is all just hype.

Get to grips with “hyping” with our new CMP Dictionary entry.

ON A LIGHTER NOTE

Sticker-in-Chief

Is there anywhere else in the world you’re liable to receive DMs laden cutesy animal cartoons from your boss, business partners, immigration authorities, and even the President herself?

On Taiwan’s leading messaging app LINE (see “Anti-Social” above) these are known as stickers, and sets can be purchased in-app catering to your favorite animal, video game, K-pop group, cartoon character, or… political party. It’s become something of a tradition for presidential candidates to release stickers sets of themselves for supporters. Let’s review a few recent ones:

Ahead of Tsai Ing-wen’s successful 2020 re-election campaign, as the opposition Kuomintang (KMT) tried to undermine her for being a single woman with a menagerie of pets, her team decided to take the “insult” and run with it, turning out cute line stickers called “Tsai’s Daily Routine” (小英的日常) that featured a feline Tsai with her cats and dog

The same year, her KMT opponent Han Kuo-yu (韓國瑜) tried to replicate her success with a sticker set co-starring Han and his pet shiba inu, although the unmistakably 長輩圖 aesthetic — this being the online slang for the “boomer graphics” shared by older folks — didn’t win over the spry sticker aficionado who commented, 「誰用這貼圖跟我對話馬上絕交」 (“If anyone sends me these, the conversation will immediately end!”).

As the nation goes to the polls again next month, they’re also going to the “Sticker Store” (貼圖小舖). Tsai’s successor Lai Ching-te has come out with a set of myself and his late Formosan mountain dog Luke (RIP). Another set stars both himself and his running mate, “cat warrior” Hsiao Bi-khim, as a dog-and-cat duo. The KMT’s Hou Yu-ih is also in on the racket with a sticker set called 哇係哩a鋼鐵侯, or “I Am Your Iron Hou” — This is a pun, OK — in which the ex-cop is depicted as an IP-safe crossover between Superman and Ironman. Suffice to say that despite Han’s landslide defeat in 2020, it doesn’t look like the party has considered a new artistic direction for Hou’s stickers.

CMP IN THE HEADLINES

Youth Unemployment? What Youth Unemployment?

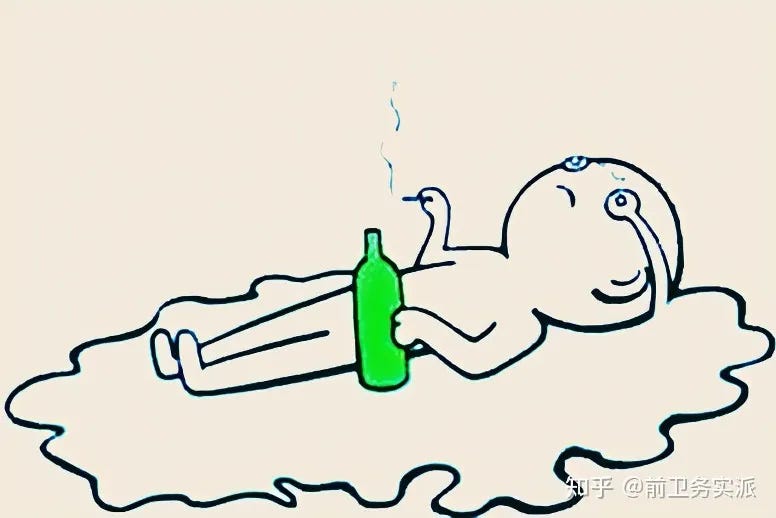

On December 8, the Wall Street Journal ran a story that looked at the implications of China’s decision not to publish youth unemployment statistics. Called “How China Made a Youth Unemployment Crisis Disappear,” the story drew on the expertise of the China Media Project in tracing the origins of the phrase “Lying Flat” (躺平), which can be found in our CMP Dictionary:

“David Bandurski of the China Media Project, which studies the Chinese media landscape, traces the phrase to a viral social-media post from an unemployed youth titled “lying flat is justice,” which inspired an entire movement “to opt out of the struggle for workplace success, and to reject the promise of consumer fulfilment.”

For more on “Lying Flat” dating back to the year of the term’s rise, see Bandurski’s article for Brookings here.

GOING GLOBAL

How Dare You, Italy!

When the Meloni government announced in July that Italy intended to exit Xi Jinping's signature trade and infrastructure program, Chinese state media made their voices heard with a string of commentaries and reports urging the G7 country to make “the right decision.” In stark contrast, Italy's formal step to withdraw last week has met with uncharacteristic quiet.

Italy’s formal withdrawal from the Belt and Road Initiative came on December 6, as the Italian foreign ministry delivered a note to Beijing stating its intention not to renew the memorandum signed by the first Conte government in 2019.

China does not seem to be happy, but unlike the small storm that ensued over the summer when news of the possible withdrawal surfaced, we can only read China's displeasure in its uncharacteristic silence over Italy's decision.

For more on Italy’s decision and China’s, well, non-response, read Dalia Parete’s summary here.

CHAIN REACTIONS

Telling China’s Story from the UAE?

On December 11, the official Xinhua News Agency ran a report in English full of self-praise of China’s developments, and how these were lauded by all foreigners present at the World Media Summit (世界媒体峰会). Among the sources quoted was Firas Hassan, the Chinese editor of Emirates News Agency (WAM). In a perfect echo of Xi Jinping’s news and propaganda slogan “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国故事), Hassan reportedly told the news service: “I learned to understand China in Beijing, and now back in the UAE, I am responsible for telling good stories of China.”

Who exactly is Firas Hassan? What is his story?

The Xinhua report mentions that Hassan earned both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Chinese language and literature at Capital Normal University in Beijing. According to his LinkedIn page, Hassan worked for several months after earning his bachelor’s for a drilling subsidiary of the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation. The next year, he moved to the marketing department at Huawei. After returning to Capital Normal University for his master’s, Hassan worked for almost 9 years for the police department in Abu Dhabi as a translator and interpreter.

One year ago, Hassan announced he had been appointed as a news editor at WAM. Since then, Chinese state media have mentioned Hassan, who is originally from Iraq, in numerous news reports, identifying him as “the Chinese editor at WAM” (阿联酋通讯社中文编辑) and praising him for his contributions to China’s external communications. He was even highlighted in a propaganda insert by the the CCP’s official People’s Daily that appeared in Indonesia’s International Daily News (國際日報), in which he was praised for “telling the China story to more people.”

China Boy Translates the China Story

In a similar interview one year ago with Haiwainet (海外网), a website operated by the overseas edition of the People’s Daily, Hassan explained that his colleagues refer to him as “China Boy” because he routinely drinks either plain hot water or Chinese tea. The interview also included a link to Hassan’s “excellent work” at WAM.

The bulk of the Chinese-language work done by Hassan and his team is translations of original WAM reports about the UAE and the Middle East into Chinese. Reports directly dealing with China, meanwhile, closely follow reporting from Chinese state media, based on our research at Lingua Sinica. This recent report on the 10-year anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative, for example, is based entirely on a report published the day before by China Daily, the newspaper run by the Information Office of the State Council.

STORYTELLERS

Taking the Pulse of Diaspora Film

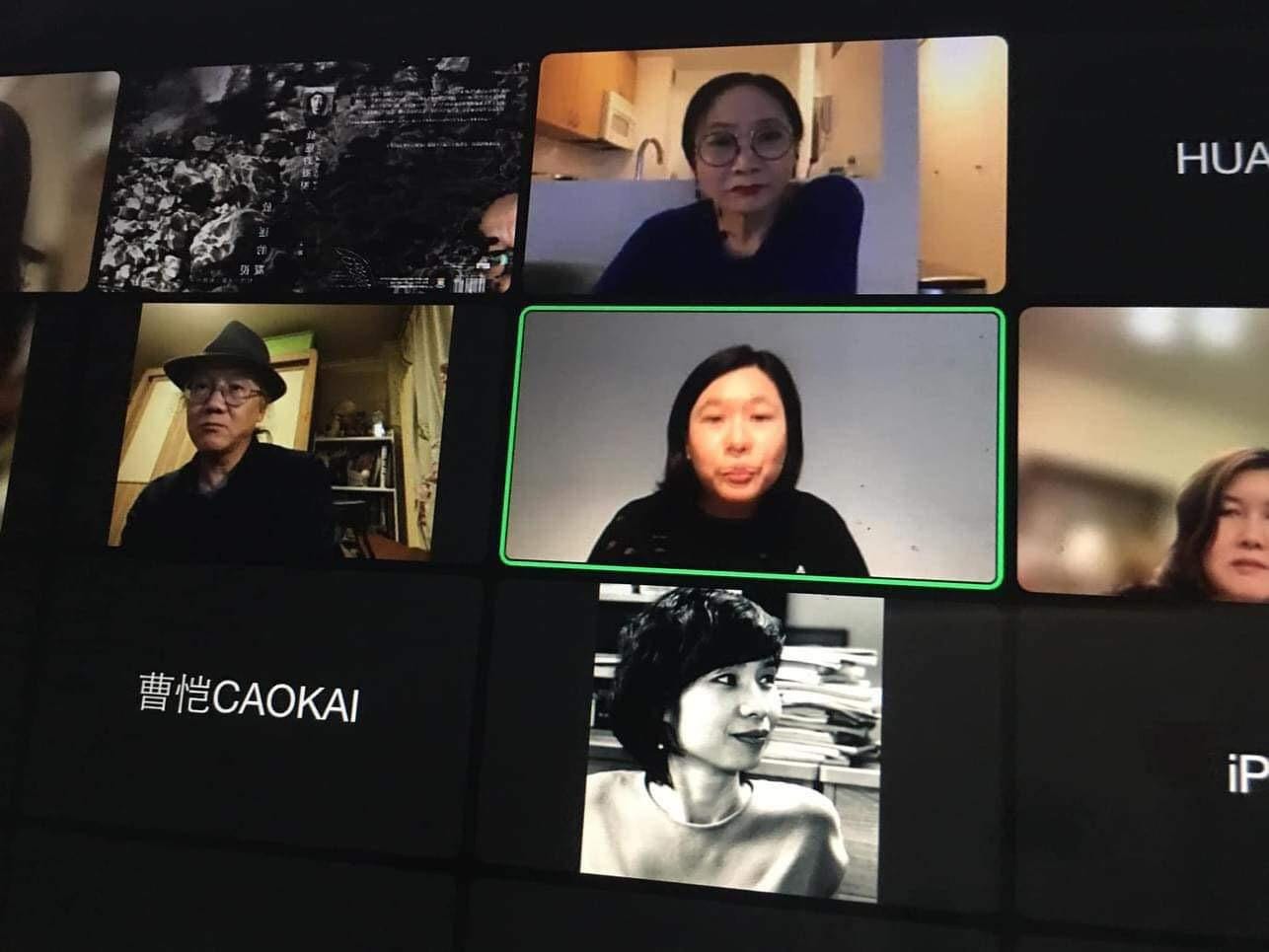

As independent Chinese filmmakers have met with a sustained crackdown on their work inside China over the past 10 years, many have moved overseas, searching out new space in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe, Japan, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

At a cross-regional forum held over Zoom on December 10, Chinese filmmakers, scholars, students and others discussed the implications of today’s “diaspora film” (離散電影). The emergence of diaspora cinema in recent years echoes the evolution of Chinese literature after the brutal suppression of the pro-democracy movement in China in June 1989. At that time, literature from China developed in three principle directions, toward “official literature” (官方文學) that approved by and palatable to the party-state; “underground literature” (地下文學), unofficial work published inside China without authorization; and “exile literature” (流亡文學), that written by Chinese in exile.

Lenses Face the Future

The recent event on diaspora film, organized by exile filmmaker Huang Wenhai (黃文海) in cooperation with the Center for Sustainable Human Rights Development (人權永續發展中心) at Taiwan’s National Chung Cheng University, drew together eight female filmmakers, who reflected on the opportunities and challenges facing diaspora filmmaking today — with New York University film professor Zhang Zhen (張真) as host. They included: Feng Yan (馮艷), whose remarks were titled “Shooting While Living” (邊生活邊拍攝); Ma Ran (馬然), whose remarks were titled “ A New Wave of Cinema in the Post-Indie Era” (後獨立電影時代與新電影浪潮); and Wu Dan (吳丹), whose remarks were titled “Collecting and Exhibiting Independent Films in China: The Possibility of Decentralization” (中國獨立電影的收藏與展映:去中心化的可能性).