Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 25 Jan

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

Warm greetings from frigid Taipei, where temperatures on the northern end of our semi-tropical island have dipped into the single digits this week — colder, for a time, than Tokyo or London. If nothing else, it’s an effective cool-down from the election fever tearing across the nation in our last issue.

In today’s newsletter, we look at how Chinese media have covered the election outcome, plus some key takeaways about PRC-directed disinformation campaigns in the run-up to the vote. Elsewhere, we tackle worrying new developments in Hong Kong’s media landscape and feature an interview with the editors of Mang Mang on the challenges facing diaspora media.

The Year of the Dragon will soon be upon us, and Lingua Sinica will be making some big changes in the next lunisolar cycle. We’re becoming more than just a newsletter. Soon, Lingua Sinica will be a platform all its own, offering regular features, interviews, and other content on Chinese-language media from all around the world. In addition to this essential reading, we will eventually offer a suite of premium content to subscribers.

We’ll share more information about our plans in due course. Until then, keep warm!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

One Election, Two Reactions

When Taiwan held its presidential and parliamentary elections earlier this year, Chinese state media took very different approaches in their coverage for domestic and international audiences.

For Chinese audiences, coverage was very limited, with a three-line official release from the state-run Xinhua News Agency. It referred to the winning candidates dismissively as the “regional leader and deputy leader” without providing any additional context. Other domestic PRC media outlets simply reprinted the Xinhua notice.

By contrast, coverage in Chinese state media aimed at foreign audiences, like the Global Times and China Daily, was much more aggressive. These outlets condemned the winning Democratic Progressive Party and President-elect Lai Ching-te (賴清德), threatened military force and warned of dire economic consequences should Taiwan cross any “red lines.”

The dichotomy is revealing. For the Chinese Communist Party, Taiwan remains an issue of extreme sensitivity, and this is especially true at election time when the free and open nature of the political process across the straits has the potential to reflect on deeper questions of political legitimacy in China.

Read our full analysis here.

TRACKING CONTROL

New Media for a New Hong Kong

The theme of the night on January 17 was “New Media Conduct [for] Hong Kong’s New Stage” (香港新階段 媒體新作為). The keynote speaker: none other than the Chief Executive of Hong Kong, John Lee Ka-chiu (李家超).

For Hong Kong media, it was not exactly a night to celebrate.

As though channeling the spirit of official numerology, so common to the rarefied discourse of China’s ruling Communist Party, Lee laid out Three Goals for news media in the Special Administrative Region (SAR). First, “promote patriotism”: second, “tell good Hong Kong stories”; third, “act as a communication channel between the government and the people.” Given the strong history of press freedom in Hong Kong, such unapologetic intrusion into the work of local media should have appalled the journalists present at the gala night. But for the event’s hosts, the Hong Kong Federation of Journalists (香港新聞工作者聯會), it was all par for the course.

The Tale of Two Press Associations

Formed in 1996 by "a group of people who love China and love Hong Kong (愛國愛港人士), the HKFJ has long been a staunchly pro-China alternative to the decidedly professional and press freedom mission-focused Hong Kong Journalist’s Association (香港記者協會), or HKJA, founded in the 1960s. In 2019, the HKJA and the Hong Kong government locked horns over the violent treatment meted out by police against reporters covering the city’s massive pro-democracy protests. Police Commissioner Raymond Siu (蕭澤頤) accused the body of issuing press cards to protect protestors and turning a blind eye to pro-establishment media. (In response, the HKJA published a list of instances when they advocated for reporters from pro-Beijing outlets, even as those outlets clamored for a crackdown on the Association.)

In the new era for Hong Kong that has followed the implementation of the national security law, the HKFJ seems to have found new prominence as a voice for journalistic compliance.

Take for example the opening ceremony for the HKFJ’s new clubhouse last month. At the unveiling ceremony for the office, located in the North Point neighborhood that has for decades hosted pro-Communist institutions, HKFJ Chairman Li Dahong (李大宏) said that the HKFJ “would not let down the honored guests” assembled for the occasion. Rather curiously for a press advocacy group, these included Lin Zhan (林枬), deputy director of the Cultural Affairs Department of the Central Government’s Liaison Office, and a special commissioner on the press from China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) — the kinds of officials that professional media unions are often at loggerheads with.

Blurred Lines and Model Workers

As it happens, Li Dahong wears many crowns in Hong Kong. As well as chairing the HKFJ, he is the chairman and editor-in-chief of the Ta Kung Wen Wei Media Group, which combines the city’s two biggest state-run newspapers, the Ta Kung Pao and Wen Wei Po. He is also a delegate to the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (中國人民政治協商會議全國委員會), the CCP-led political advisory body. Li is a prominent representative, in other words, of a model of state-led journalism that doesn’t question political power but serves as its megaphone.

For readers familiar with the All-China Journalists Association, the HKFJ is probably at this point sounding awfully familiar. The ACJA, as we have covered in numerous pieces over the years, is not your typical industry organization. Even though it describes itself as “a national non-governmental organization” the ACJA in fact serves as an important layer for exercising the Chinese Communist Party’s control over news organizations and the country’s more than one million registered journalists, rewarding compliance with the CCP’s demands and punishing perceived failures.

Tellingly, the HKFJ gala dinner on January 17, where John Lee gave media their marching orders, also served as the launch ceremony for a new body in the ACJA’s mold: the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Greater Bay Area Media Federation (粵港澳大灣區媒體聯盟). As Li Dahong addressed the crowd, he said in a nod to one of Xi Jinping’s key propaganda phrases that this new mega-group would endeavor to “tell Greater Bay stories well,” and that it would share the HKFJ’s foundational mission “to support the SAR government.”

That’s the kind of “journalism” any autocrat can get behind.

MISREADINGS

China’s latest pique over the ills of “Western media” misses the point.

State media have had a field day this month with the cover of the January 13 edition of The Economist, “China’s EV Onslaught,” which depicted an in-bound meteor shower of China’s latest electric cars, poised to strike the Earth. China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), state media, and their affiliates on Twitter re-posted the image in quick succession as an example of the hypocrisy of how China is portrayed by Western media, comparing it to the magazine’s cover from 2013, which painted China as poising the globe on Armageddon as “The World’s Worst Polluter.”

The idea is that no matter what China does — pollute or invest in green energy — Western media inevitably find a way to attack the country. “The self-contradicting reports reflect a consistent narrative,” wrote the Chinese Consulate General in Sydney’s official account. “China is the bad guy.”

But not so fast.

Such posts entirely bypassed or omitted the content of the article, which argued that although the West fears Chinese expansion into electric vehicles (now making them the world’s largest car exporter), it should in fact “welcome them.”

The original tweet pointing out the contrasting covers came two days before state media, and apparently from outside the state media machine — from Sun Sibei, a PhD candidate at Macau University. Sun has made previous posts contrasting Western media reports or positions from experts over time to suggest hypocrisy in their stance on China. Sun has also co-written a paper on how Chinese diplomats use Twitter to push “well-structured narratives” about the country abroad as a “PR tool.” He has claimed that although state media “copied” his tweet, nonetheless The Economist’s “sensible commentary is obscured by sensational cover art and headlines, which is what most people see.”

Read the full story at the China Media Project.

QUOTE / UNQUOTE

Charting a Course for Diaspora Media

Last week here at Lingua Sinica, we published translations of recent writing from Mang Mang (莽莽), an independent magazine based in Europe that was born out of the wave of resistance in China and globally in 2022 that became known as the White Paper Movement (白紙運動). This week, we reached out to editors at Mang Mang to learn more about the challenges they face in 2024, and the aspirations that motivate their community. We encourage our readers to check out Mang Mang, and also to pledge their support.

Lingua Sinica: In your New Year’s letter, you spoke about “the precious embers” (珍貴的火種) of the protest movement in China and around the world in late 2022. What are those embers, and how will Mang Mang play a role in continuing what the movement began?

Mang Mang: The “precious embers” are the values of democracy and freedom cherished by every activist. They are not just ideas but have become the basis of consensus in new actions and organizations, and have transformed from an abstract idea into a real practice. As the movement offline has ebbed, we hope to transform it into a daily "resistance" movement, and in the future we will continue to initiate dialogues with different ethnic groups in order to eliminate conflicts and misunderstandings. We will use our mother tongues to write about dispersed people and to write and record our history.

LS: Mang Mang is available both in print and online — and now you’ve moved to Substack as well. Could you talk just a bit about your distribution strategy? How do you address the challenge of reaching, and expanding your readership, keeping them engaged, and so on, while considering basic issues of security?

MM: Before moving to Substack, our main online platform was our own homepage. But this was forced to shut down after suspected cyberattacks, possibly originating from China. As a result, we transitioned to Substack. Currently, our inaugural print magazine is distributed through collaborations with independent bookstores, with sales taking place in Asia, Europe, and the Americas, with the highest sales in Taiwan.

We face two major challenges: for the print magazine, we lack a safe platform for online sales in Europe or the Americas, making it inconvenient for the scattered Chinese diaspora worldwide to purchase and read it. The second challenge is related to security concerns, as we are unable to expand collaborations with writers and securely pay them for their contributions, causing the overall progress to be slower. We engage with readers through platforms such as Instagram, X, etc., and closely follow the growth and development of Chinese youth diaspora communities around the world. This allows us to maintain continuous contact with readers.

LS: What do you see as the top challenges facing Mang Mang in 2024? And as readers, or members of the broader global community, what can we do to help?

MM: In 2024, Mang Mang's greatest challenge is sustainable development, a challenge faced by almost all Chinese youth diaspora communities that we observe. After the emotion-driven social movement, we need to discuss survival strategies under the shadow of transnational repression, censorship, and surveillance. This involves securing the necessary funds, finding ways to continue activities overseas, and confronting internal debates and conflicts.

For Mang Mang, writing and recording in and of themselves are forms of social engagement. We hope to preserve a platform of native language writing, allowing stories deleted by power to be recorded. Mang Mang and similar Chinese independent media platforms cannot rely on commercial solutions for survival, and we should not be narrowly understood as publicizing any particular political ideology. We do not wish to be confined to stereotypical impressions of the Chinese community but rather to place ourselves on a wider global stage. That way, the struggles, pains, difficulties, and resistance we experience can be seen by the world, and people from other regions can become aware of the existence of this type of diversity and complexity when it comes to China.

IN MEMORIAM

News Crossing Party Lines

On January 15, 2024, just as Taiwan’s Democratic Progressive Party (民進黨) celebrated its third consecutive presidential election victory, pro-democracy activist Shih Ming-teh (施明德), a legendary figure in Taiwan remembered for his defiant activism for a democratic Taiwan, passed away from cancer at Taipei’s Veteran General Hospital. He was 83.

Known as the "Nelson Mandela of Taiwan," Shih dedicated his life to activism from his youth, fighting for democracy and championing human rights. His resistance to Kuomintang (KMT) rule in the period prior to the lifting of martial law in 1987 earned him two stints in prison, totaling more than 20 years — much of this time in solitary confinement. He later became a key leader of the DPP, though later a fierce critic of President Chen Shui-bian, calling for his resignation over allegations of corruption in 2006.

On the morning of Shih’s death, Taiwanese news outlets were flooded with news of his passing. Sympathetic coverage could be found in both outlets regarded as pan-green (favoring the DPP), such as the Liberty Times (自由日報), as well as in stalwart pan-blue outlets (favoring the KMT), including United Daily News ( 聯合新聞) and China Times (中時新聞).

Garbled Facts in China

News of Shih’s death was reported in a handful of news outlets inside China that are sometimes given greater leeway in reporting outside affairs. These included the Global Times, a spin-off of the official People’s Daily newspaper, and Guancha, a privately-owned Shanghai outlet with close ties to the leadership. Both are known to take a strong nationalist and pro-CCP tone in their coverage. The brief story from the Global Times emphasized only Shih’s opposition in 2006 to Chen Shui-bian, a figure much despised by the PRC leadership. In its longer introduction to the activist’s life, Guancha suggested misleadingly that he had opposed Chen’s “autocratic dictatorship” (独裁专制), an allegation often asserted in the past by PRC state media, when in fact the chief issue was corrupt governance under the democratically elected leader.

In its coverage of Shih’s passing, following Taiwan’s China Times, Zhinews (直新闻), a multimedia brand of the state-run Shenzhen Satellite TV under the city’s newly-created international communication center (ICC) for external propaganda, reported without historical context that the Taiwan activist had been jailed for promoting Taiwan independence. While Shih was indeed jailed for sedition between 1962 and 1977 for advocating Taiwan’s independence from China, independence at the time was about independence from the KMT-led Republic of China (ROC). By missing out such important facts — including the specific years of Shih’s imprisonment — the Zhinews report seemed to suggest the seditiousness of calls for Taiwan independence in a contemporary context.

ANTI-SOCIAL

Hong Kong Ruled by the Little Red Book

In the infamous leftist riots that shook Hong Kong in 1967, Communist sympathizers marched through the streets and surrounded the Governor’s house, waving Little Red Books filled with Chairman Mao’s quotations. For a tense moment, it looks like the Cultural Revolution could spill over the border and overrun the then-British colony in a sea of red. Now, fifty-seven years later, there are renewed concerns in Hong Kong, from pro-Beijing stalwarts no less, that the city is being “ruled by the Little Red Book” — but in a different form.

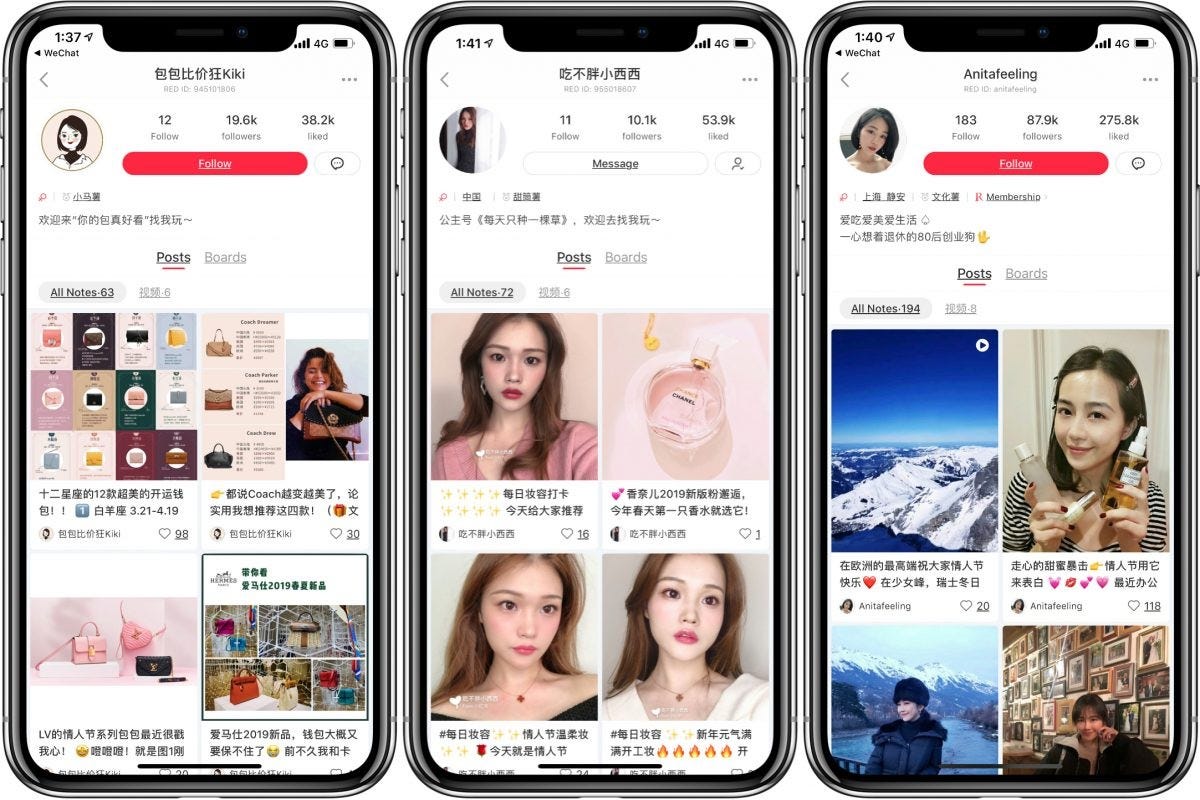

Last week, Paul Tse Wai-chun (謝偉俊), a member of Hong Kong's Legislative Council, said publicly that he had received feedback from local residents that the government deferred too much to opinions expressed by PRC nationals on the popular Instagram-like app Xiaohongshu (literally “Little Red Book”), and that this showed a tendency to “favor one side and discriminate against the other” (厚此薄彼). He even suggested that the situation had now become one of “Xiaohongshu ruling Hong Kong” (小紅書治港).

Responding in writing to this suggestion, Tsang Kwok-wai, the Secretary for Constitutional and Mainland Affairs, stated that the HKSAR Government attaches equal importance to views about Hong Kong, whether expressed in local or mainland social media.

Painting the City Red

To appreciate the irony, some background is necessary. Hong Kong’s District Councils, while largely toothless, used to be the territory’s only democratically representative political bodies, and a landslide victory for the pro-democracy camp in 2019 saw pro-Beijing officials lose control of all but one council. Changes introduced after this humiliating defeat disqualified opposition figures, reduced elected seats to a fraction of what they used to be, and ensured only “patriots” could stand for office in the future. This was sold to voters as an improvement. Pro-democracy councilors, went the official line, had “politicized” the bodies and distracted them from livelihood issues. By contrast, voters were promised, new “patriots-only” DCs would finally be able to get down to brass tacks.

The reality, however, has been underwhelming. After elections last month (see our 14 December newsletter for the full story) patriotic District Councillors' first priority has instead been proposing a stream of expensive and gaudy “check-in points” (打卡點) for Xiaohongshu users — installations intended more to appeal to mainland visitors than improve the lives of local residents.

Any criticism of pro-China policymakers in today’s Hong Kong, where the political opposition has been effectively banned and its leaders imprisoned, is surprising. In this case, the individual launching the criticism makes it even more unexpected. The Honorable Paul Tse represents the tourism industry in the Legislative Council — for more on Functional Constituencies, read Christine Loh — and is fervently pro-Beijing. He recently vowed to introduce legislation cracking down on pro-democracy small businesses.

CHAIN REACTIONS

Hot Propaganda in the Frigid Nordic Winter

"Let the world appreciate China and let China embrace the world," reads a banner across the top of the Nordic Chinese Times (北欧时报), or NCT, a print newspaper and website that claims to reach overseas Chinese communities and others interested in China across 20 cities in the five Nordic countries of Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Iceland.

Visit the website of the Nordic Chinese Times this week and you may be nonplussed to discover that its top headline is a dull piece of propaganda from China’s Guangxi Daily (广西日报), the official Communist Party mouthpiece of the southern region, about the delivery of a government work report by the local Party chief.

What could possibly connect a Chinese newspaper based in Stockholm with political events in Guangxi?

With a bit of digging, Lingua Sinica found that the Nordic Chinese Times was launched in 2009 by He Ru (何儒), a native of Guangxi who arrived in Sweden in 2006 and is now president of the Copenhagen-based Nordic-Chinese Chamber of Commerce (北欧中国商会). He Ru told China’s official state broadcaster CCTV in 2019 that after arriving in Sweden he realized that “it was hard to find news about China in the local media, and if there was news it was largely negative.” He Ru was reportedly incensed by Western media coverage ahead of the Beijing Olympic Games in 2008. He launched the Nordic Chinese Times the next year, urging his colleagues, according to the CCTV report, to “stick to the principle of impartiality.”

While the Nordic Chinese Times continues to call itself a “neutral media” (中立媒体), our survey of all 31 news reports in the website’s “China News” section on January 24 found that 100 percent of these were sourced directly from Haiwainet (海外网) — the official website of the overseas edition of the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily — which lists its mission as “spreading China's voice and serving our compatriots around the world.” The overseas edition of the People’s Daily reported in October 2016 that it had signed a cooperation agreement with the Nordic Chinese Times, reaching "a consensus on in-depth cooperation." According to the agreement, the Nordic Chinese Times would run four full pages of People’s Daily content in each of its daily editions, and would “use multimedia means to radiate [the paper’s content] out from the Swedish capital of Stockholm out to the five Nordic countries.” That cooperation is now reflected by the inclusion of the People’s Daily logo on the paper’s masthead.

Radiating his partial view of impartiality, He Ru’s website ran his enthusiastic comments on the CCP’s 20th National Congress in October 2021, which were also printed in the pages of Guangxi Daily. "General Secretary Xi Jinping's important speech,” he said, noting remarks Xi had made to the Guangxi delegation, “made my heart pound like a spring breeze.”

SPOTLIGHT

Democratic Resilience Forum

On January 20, 2024, the Taiwan Information Environment Research Center (台灣資訊環境研究中心), also known as IORG, held its annual Forum on Democratic Resilience (民主韌性論壇), inviting disinformation researchers from Taiwan and Japan to share their insights on the challenges facing democracies globally in the face of interference from authoritarian regimes.

In his opening address to the forum, Taiwan’s minister of foreign affairs, Joseph Wu (吳釗燮) noted the success of recent elections in Taiwan despite the looming challenge of disinformation from China. Taiwan’s experiences as “a resilient and successful democracy” could serve as an example for other democracies, he said, and Taiwan is “willing to share.”

In a presentation on his organization’s election-related research, IORG Co-Director Chihhao Yu (游知澔) highlighted three main approaches in recent CCP disinformation campaigns directed at Taiwan:

Undermining democratic operations and denying democratic values;

Leveraging AI-generated content and existing social divisions to make identifying and neutralizing disinformation more difficult;

Professionalizing and focussing on creating a market for inexpensive information manipulation in key strategic areas.

A full video of the IORG event is available on YouTube. For more on the organization’s work, visit their website here.

IN THE NEWS

Free Election Faux Pas

A Chinese investigative journalist now based in Tokyo, where he has been highly critical of China’s ruling CCP, has been banned from Taiwan for five years after derogatory comments about people with disabilities and Taiwan’s election process.

While appearing on “The Night Night Show” (賀瓏夜夜秀), Wang Zhi’an (王志安), a former reporter for the state-run China Central Television (CCTV), appeared to mock people with disabilities. During the recorded appearance, Wang said he felt Taiwan’s elections were a “show” (秀) in the way they featured both popular singers and people with disabilities. For this latter remark, he used the word “invalid,” or canbingren (残病人), considered derogatory in Taiwan but acceptable in China. “Invalids are being pushed on stage to stir up emotion,” Wang said to the audience, leaning his head back with a quivering face before adding with slurred speech: “Support the DPP!”

Many viewers in Taiwan understood Wang’s antics to be directed at prominent and well-respected human rights lawyer Chen Chun Han (陳俊翰), a DPP legislative candidate who was born with spinal muscular atrophy and had both legs amputated. In a response to television reporters, Chen focused blame on the television program hosts. “When the Chinese person in question made these inappropriate remarks and comments, the onus was in fact on the hosts to speak up and prevent such language,” he said. On the question of Taiwan’s elections, he said: “China doesn't even have the freedom to hold elections, yet it turns around and mocks Taiwan's democratic and free election methods, which I find absurd.” Chen added that Wang’s derogatory attitude towards people with disabilities reflected more general social attitudes in China, which attempts to accommodate people with disabilities but assumes they lack agency or the capacity to contribute to society.

Once known inside China for his exposés on corruption and medical malpractice, Wang found that his investigative work had become impossible given the newly harsh restrictions imposed under Xi Jinping’s leadership after 2016. He left for Japan, founding his own YouTube channel that has often been critical of the CCP and its human rights record. Wang was visiting Taiwan this month to cover the elections for his channel. Taiwan’s National Immigration Authority subsequently announced that Wang’s appearance on the show violated his statement of travel (“tourism”), and responded by issuing a five-year ban.

The show’s hosts and producers have since apologized publicly for laughing along with Wang. Wang offered a non-apologetic apology, saying that he was willing to apologize “if Lawyer Chen feels offended,” but adding that “this does not conflict with my condemnation of the DPP for using people with disabilities as electoral tools.”

STORYTELLERS

For a Short Documentary, A Very Short Shelf Life

On January 8th, a short documentary released online by NetEase News suggested that China has still not eradicated poverty — something Xi Jinping announced as a “complete victory” three years ago. The production, “Working Like This for Thirty Years” (如此打工三十年), centered on the tough lives of migrant workers in Hefei, the provincial capital of Anhui. Just one day later, the video was removed from the BiliBili streaming service, after garnering a large number of views (it can still be found in full on YouTube).

The documentary was apparently too much negative energy for China’s media control authorities, who since 2013 (early in Xi’s first term) have emphasized the need for “positive energy” — meaning uplifting messages as opposed to critical or negative ones.

For decades, migrant workers have been on the wrong side of China’s hukou system, which only allows residents officially registered in more developed urban areas access to fixed work contracts and benefits. As the NetEase documentary makes plain, the system leaves out millions who still travel from the countryside to the cities for better wages. Callous enterprises take advantage, only offering part-time gig work.

“You see how many people there are under the bridge? Lots of people can’t get work” says one migrant worker in his early 50s, pointing to a crowd lining up at 4 A.M. in the hope of finding today’s odd job.

The rights of migrant workers has been a continuous problem in Chinese society since the first days of reform and opening up in the 1980s. The NetEase short documentary implies their situation is fundamentally unchanged — offering glimpses into lives so poor that some cannot even afford 380 RMB (just over 50 dollars) for health insurance.

For some, the documentary seems to have been an eye-opener. “I have always turned a blind eye when I saw people begging on the street”, wrote one netizen on Zhihu, adding that “[the] gap between the rich and poor has not been fundamentally changed, and the gap between urban and rural areas has further widened.” Some imitation tributes have since popped up — one simply a video walk around a migrant enclave in the suburbs of Xi’an in the very early hours of the morning, showing how many still work like this every day.

The fact that the NetEase documentary was filmed in Hefei provides an interesting subtext. Back in November last year on Hefei’s Patriot Lane, tens of thousands publicly mourned the passing of former Premier Li Keqiang (See “Flowers in Hefei”). It was Premier Li, sidelined within the CCP's Politburo Standing Committee, who punched through the veneer of poverty reduction claims in June 2020, when he admitted that more than 60 percent of China's population subsisted on less than 140 dollars a month.

DID YOU KNOW?

Once an Expat Getaway, this Chinese Hill Resort Has Become a Symbol of Bilateral Exchanges

Guling Mountain, formerly known as “Kuliang,” was a resort enclave that was established by foreign missionaries in the hills above Fuzhou in 1886, and became a place where many in the foreign expat community went to escape the summer heat. After 1949, Guling Mountain became a summer resort for the local government, and the area was built-up and expanded to include large hotels and other amenities.

Since 2021, Kuliang has been mythologized as a site epitomizing the spirit of people-to-people exchanges, and the idea that deep interpersonal connections far below the heights of state-to-state diplomacy can become the foundation of a sound bilateral relationship.

While many local governments around the world value such “exchanges” for financial and cultural reasons, “exchange” (交流) has always been viewed as a practical political tool by Beijing, and all of China’s “exchange” organizations have been assigned political missions. The US-China People’s Friendship Association (USCPFA), for example, has more than thirty sections across the United States that promote “positive ties.”

While its activities are not usually overtly political, the USCPFA Statement of Principles includes the following: “We recognize that friendship between our two peoples must be based on the knowledge of and respect for the sovereignty of each country; therefore, we respect the declaration by the United States of America and the People’s Republic of China that the resolution of the status of Taiwan is the internal affair of the Chinese on both sides of the Taiwan Straits.”

Some recent examples of external propaganda using the packaged Kuliang legacy: