The Push and Pull of Press Freedom in the Philippines

Communication specialist Gian Libot talks censorship, Chinese influence, and other challenges facing the media in the Philippines.

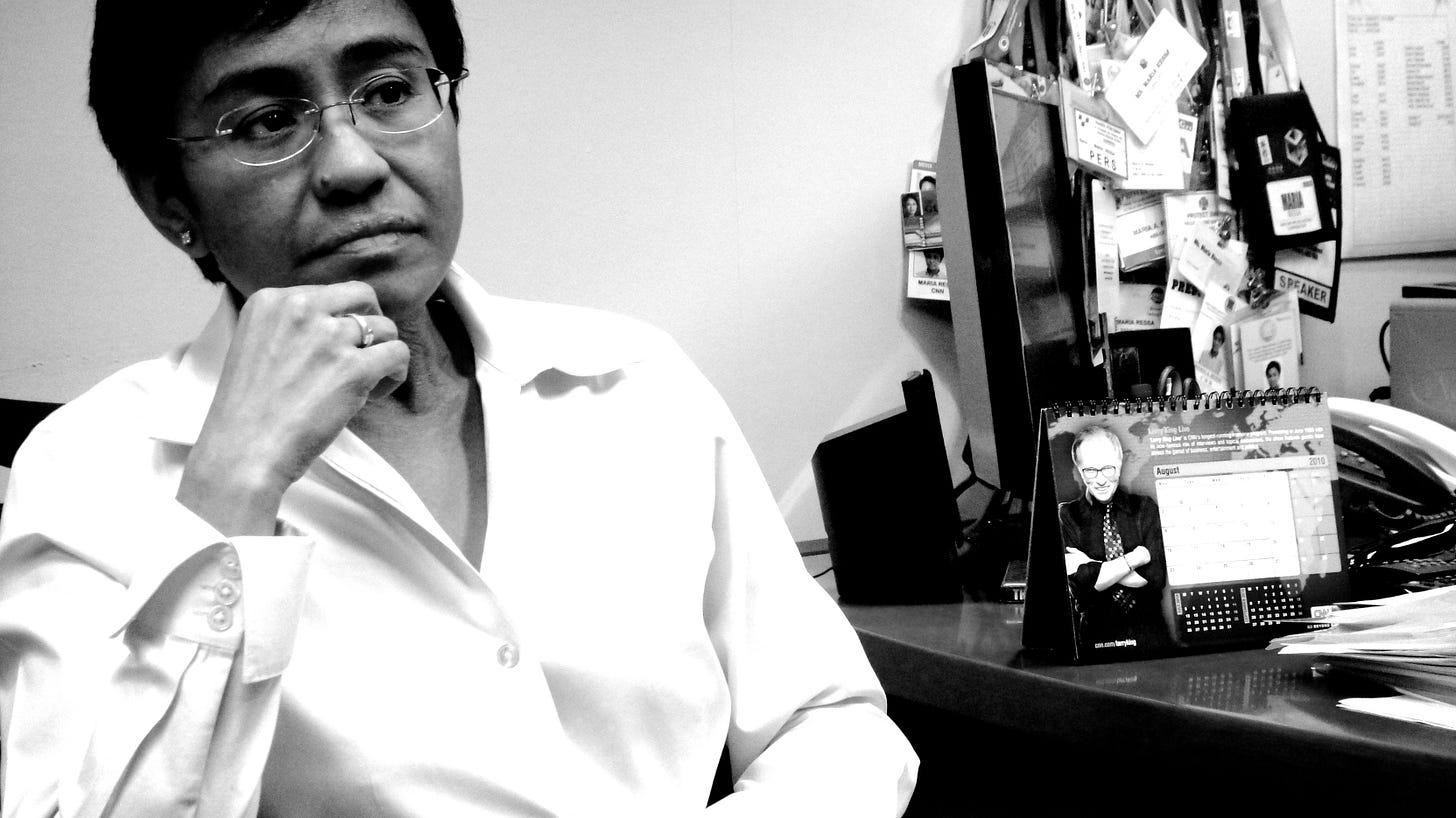

When it comes to the media, the Philippines is a study in contrasts. It has one of the most vibrant media landscapes in Southeast Asia. Maria Ressa, the veteran investigative reporter and co-founder of the online outlet Rappler has become an outspoken global voice for press freedom, and recent journalism award honorees have also included Rappler’s John Nery and Philippine Star editor-in-chief Ana Marie Pamintuan. At the same time, the Southeast Asian country is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist — a place where reporters regularly face violence and lawsuits aimed at silencing their work.

Aside from the Tagalog and English-language media that dominate the scene, the country has a relatively strong Sinophone media space. Ethnic Chinese have lived and traded in the Philippines for over 500 years, and the country’s first Chinese-language newspapers are over a century old. As tensions between Manila and Beijing have grown in recent months over competing territorial claims in the South China Sea, questions about the role of domestic Chinese-language media in the country — known historically for their pro-China bias — have joined broader national concerns about PRC influence.

To make sense of this complex and dynamic media environment, we spoke with Gian Libot, Digital Engagement Specialist for Internews Philippines, an international organization that supports over a hundred independent news outlets around the world.

Lingua Sinica: To start with the broader strokes, what would you say is the current state of press freedom in the Philippines?

Gian Libot: I’d say that on the surface press freedom appears to have slightly improved or at least been less constrained by the current administration — primarily based on rhetoric alone. There's been less pressure from the president and the government to attack media institutions. In fact, there's been more outreach and engagement with the media compared to previous years. One critical positive aspect is the outcome of landmark cases involving crimes against journalists. For example, the Maguindanao Massacre, one of the country's worst attacks on journalists, resulted in a verdict in 2019, marking a step forward for press freedom.

In theory, things might seem better. But journalists, particularly those in smaller regions outside of Metro Manila, would tell you otherwise. The nation's placement on the Reporters Without Borders World Press Freedom Index shows that journalist safety remains a significant concern. Out of 180 countries, we are placed 134th, which is still relatively low. Even if the government isn’t as openly hostile, threats to local media remain.

LS: What do those look like on the ground?

GL: Journalists are still being harassed, attacked, and even killed. Just last year, a radio broadcaster was murdered. According to the Center for Media Freedom & Responsibility (CMFR) 12 journalists and media workers have been killed in the line of duty from 2019 to October this year. And that’s just the deaths we know about. There’s a lot of harassment, legal pressure, and other forms of intimidation that don’t always make the headlines.

One thing that's become pretty common in the Philippines — especially under the last Duterte administration [2016-2022] — is “red-tagging.” This is similar to McCarthyism in the present era. Specific individuals or groups are accused of being connected to the communist insurrection [the world's longest ongoing communist insurgency, once supported by China].

Human rights advocates have been among the many individuals targeted by this, and regrettably, journalists have also not been exempt. As a result, a body called the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELAC) was created. This task force was set up to focus on counter-insurgency efforts, particularly against the communists in the Philippines. This group became vocal about labeling specific individuals as linked to the rebellion. And it wasn’t just activists — it included high-profile politicians and journalists. At that time, there was much fear and pressure among journalists. There’s been progress, but we’re still far from where we need to be in terms of safety and press freedom.

LS: What are the biggest challenges journalists in the Philippines currently face?

GL: I think journalism's biggest problem right now is really about survival. The business model is falling apart. There are fewer and fewer jobs, and many legacy media outlets have shut down since the pandemic hit. There’s also been a heavy push for digital content, but not all journalists or media outlets have the skills or resources to adapt to this new landscape. One of the most concerning trends right now is the rise of "lawfare" — using the legal system as a weapon to attack journalists.

I think journalism's biggest problem right now is really about survival.

In the Philippines, one of the biggest tools used in lawfare is the Cyber Libel Law. Journalists are getting convicted with this left and right, and it is putting their work at risk. First, dealing with the legal process itself can be frustrating and tiring. But the bigger issue is the threat of legal action. It’s like a constant sword hanging over their heads, and it creates this climate of fear. A lot of journalists end up self-censoring just to avoid the headache of dealing with a lawsuit.

Maria Ressa’s case is probably the most well-known example of this. She faced cyber libel charges. At one point, she was the target of almost 46 charges brought against her news outlet, Rappler. With the possible exception of one case that may still be pending before the Supreme Court, I think the majority of those have now been dismissed. Although Rappler is the most well-known example, however, it's crucial to keep in mind that there are many other cases as well. Numerous other journalists and media outlets face similar risks, particularly in cases of cyber libel. In actuality, a much larger number of people in the media are being impacted by this type of legal pressure.

LS: How has this law been weaponized as a means for the authorities to attack journalists?

GL: Over the years, we have all seen how the defamation law has been used to pressure journalists. Traditional media, digital outlets, and journalists posting on social media are all affected by it. This law has become a tool for lawfare, in which the justice system is employed to intimidate or silence people. Since the main issue with the current system is that criminal libel includes risks of incarceration, there are now calls for decriminalizing libel. Many ask, “If we can't remove libel in general, why don't we just decriminalize it?”

Over the years, we have all seen how the defamation law has been used to pressure journalists. Traditional media, digital outlets, and journalists posting on social media are all affected by it.

Civil libel is a more private matter in which you will likely be dealing with legal bills and potentially some damages. When it's criminal, however, it's more serious. You're dealing with the full weight of the state, and the cost is not only financial but also personal. Journalists are forced to deal with an endless stream of cases. Because the financial and emotional costs can be so great, individuals often simply settle with the accuser, whether that person is a public personality or a politician. In the end, the system shields the powerful and silences those who attempt to hold them accountable.

I would also say that the challenging thing with cyber libel these days is that some journalists have also started using cyber libel against other individuals as well, especially influencers or think tanks that have attacked their reputations.

LS: Do you think that journalists are self-censoring due to this law?

GL: It’s really hard to talk about this without a real study on self-censorship, but it’s no secret that in many journalism communities, there is a certain degree of self-censorship. This was especially true during the last administration when President Duterte was openly attacking media workers and targeting specific journalists. That kind of behavior creates a chilling effect. It makes people think twice before publishing anything that could put them in the crosshairs.

It’s no secret that in many journalism communities, there is a certain degree of self-censorship.

I can’t say for certain if this led to less critical reporting, though. There was still some excellent journalism during that time, particularly in covering sensitive issues like the drug war or human rights violations. But you can’t ignore the fear that comes with it. Many journalists always had that fear in the back of their minds. We’ve heard it over and over in safety training sessions we've run with journalist unions — reporters would say they genuinely feared for their lives when covering these topics, knowing that the state didn’t like how some stories were being told.

LS: Changing directions a bit, what specific initiatives or partnerships have you observed in the Philippines between the PRC and local Chinese-language media?

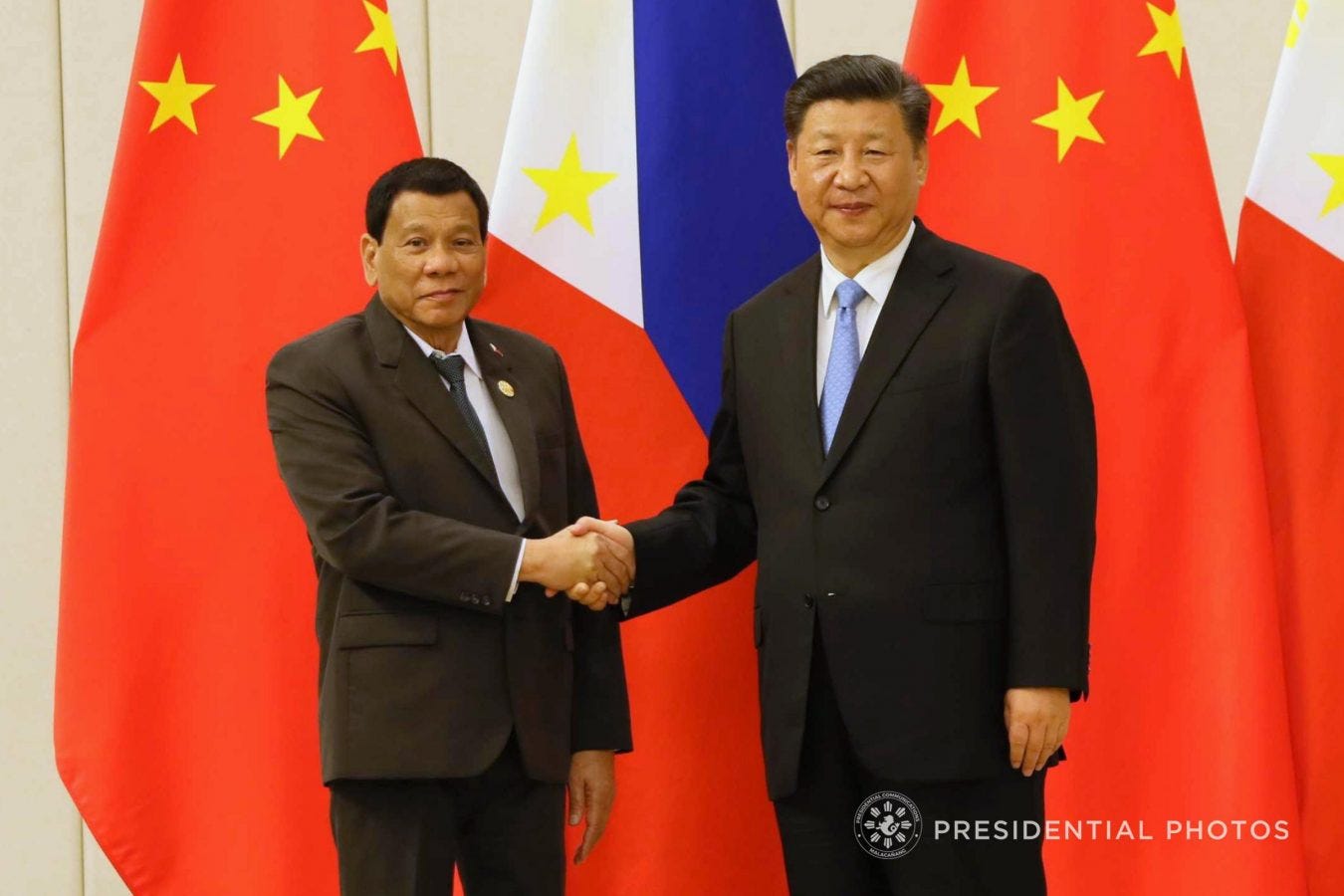

GL: From what I know, the Philippine government under President Duterte signed a few content-sharing agreements with Chinese state media. Some Philippine media personalities visited China as a result of the communications office of the Philippine government collaborating with Chinese outlets to promote exchanges.

I also know that Chinese state media themselves have local Filipino-language broadcasts here. There have been some efforts to sign sister-city engagements between, say, Guangzhou and a city in the Philippines, and these could include some kind of media content-sharing provision.

The Philippines has a profound and long history with Chinese immigrants. For example, Binondo is one of the oldest Chinatowns in the world, dating back to the Spanish colonial era — around 300 years ago. That long history has shaped many connections between the two countries.

The identity of Filipino Chinese is unique. They’ve been in the Philippines for so long, and their societal role is deeply rooted in the country’s history.

The identity of Filipino Chinese is unique. They’ve been in the Philippines for so long, and their societal role is deeply rooted in the country’s history. You can’t really compare them to the newer wave of immigrants, especially those from China who are more directly tied to the Chinese state. The channels that exist between the two countries, particularly in the Filipino-Chinese community, have been around long before Chinese state media started getting involved. While there may have been some informal connections, like through cultural exchanges, I’m not sure how much control the Chinese state has over these channels or how directly involved they are. It seems like these relationships were already in place long before the government started playing a bigger role.

LS: How does the Filipino-Chinese community differ from Chinese populations in other countries, and how has it been changing in more recent years?

GL: I wouldn’t say the Chinese-language media in the Philippines is the same as in some other Asian countries, where the Chinese community is more isolated or separated from the rest of society. The Filipino-Chinese community here is pretty integrated and immersed in the broader Filipino society, so there isn’t that sense of separation. That’s why you don’t often see Chinese-language media here focusing exclusively on Mandarin content. In fact, many of the earlier waves of Chinese migrants didn’t even speak Mandarin — they spoke Hokkien or other languages more common in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

But things have changed with the more recent wave of migrants, especially during the last administration when offshore gambling companies brought in many Chinese workers. These new arrivals have created their own smaller communities, so now there are sort of two distinct layers of Chinese communities: the older, integrated Filipino-Chinese community, which is closely tied to mainstream society, and the newer groups that might still rely on their own sources of information, including social media apps and platforms more familiar to mainland China.

LS: What impact do social media platforms have on the information environment in the Philippines? And which ones are popular?

GL: Facebook is huge in the Philippines. It’s the go-to platform for so many people. According to the Reuters Digital News Report, social media has become the main news source for many Filipinos, even outpacing traditional media in many ways. That said, TV and radio are still very popular, especially outside urban areas.

The Philippines has a high internet penetration rate, but there’s still a digital divide when it comes to access. In cities, internet and mobile services are much better, so people rely more on online platforms. But in rural areas, people still turn to traditional media like radio or TV for news. That said, things are getting a bit mixed up now. Many radio stations, for example, will stream their broadcasts on Facebook Live, so people are consuming both traditional and digital media at the same time.

LS: Do you think that members of the Chinese-Filipino community, particularly older generations, are influenced by fake news in Chinese or content farms?

GL: From what I've seen, it doesn’t seem like Chinese-language media or fake news from China has had a significant impact on the Chinese-Filipino community. They don’t really need to turn to Chinese-language media to get Chinese state perspectives. There are local think tanks that produce content in English and Filipino that already echo these positions. This kind of content is easily accessible, and you’ll often see it in major newspapers like the Manila Times, especially in the opinion sections, where you’ll find analyses that echo the Chinese government’s stance.

The younger generation of Filipino-Chinese aren’t as fluent in Mandarin anymore. A lot of them probably don’t even speak it at all.

I think the older generation might be more susceptible to it, but the younger generation of Filipino-Chinese aren’t as fluent in Mandarin anymore. A lot of them probably don’t even speak it at all. And even if there’s Mandarin-language content out there, it’s not really necessary for these messages to get through. A lot of it is being picked up by local media, and we see it in places like YouTube, where Filipino scholars or commentators share views that align with Chinese state media.

LS: Do Filipino-Chinese play an important role in mass media ownership?

GL: The interesting thing about the Filipino-Chinese community is that there’s no single, unified group. As I mentioned earlier, they’re really integrated into society, so when national polls are conducted on issues like the South China Sea or offshore gambling, they’re typically just lumped in with the general Filipino population. There’s no specific breakdown for them.

That said, many of the wealthiest people in the Philippines are of Filipino-Chinese descent, and they own major industries. But it doesn’t seem like they use their influence in a way that’s particular to the Filipino-Chinese community. They don’t operate as a monolithic group. They’re more like any other powerful elite in the country.