Telling Better China Stories

As publishers try to reach global audiences with compelling stories from Chinese authors, they face hurdles from a state that understands storytelling only through the lens of national soft power.

For part four in our series on book publishing in the global Sinosphere, we look at a paradox at the heart of China’s soft power push — how the leadership’s insistence on telling good stories about themselves is squeezing out real, human stories that could genuinely appeal to international audiences and bring ordinary people closer together.

CMP researcher Alex Colville speaks with independent publishers who are trying to fill that gap but have to navigate the shoals of both PRC authoritarianism and the whims of Western readers.

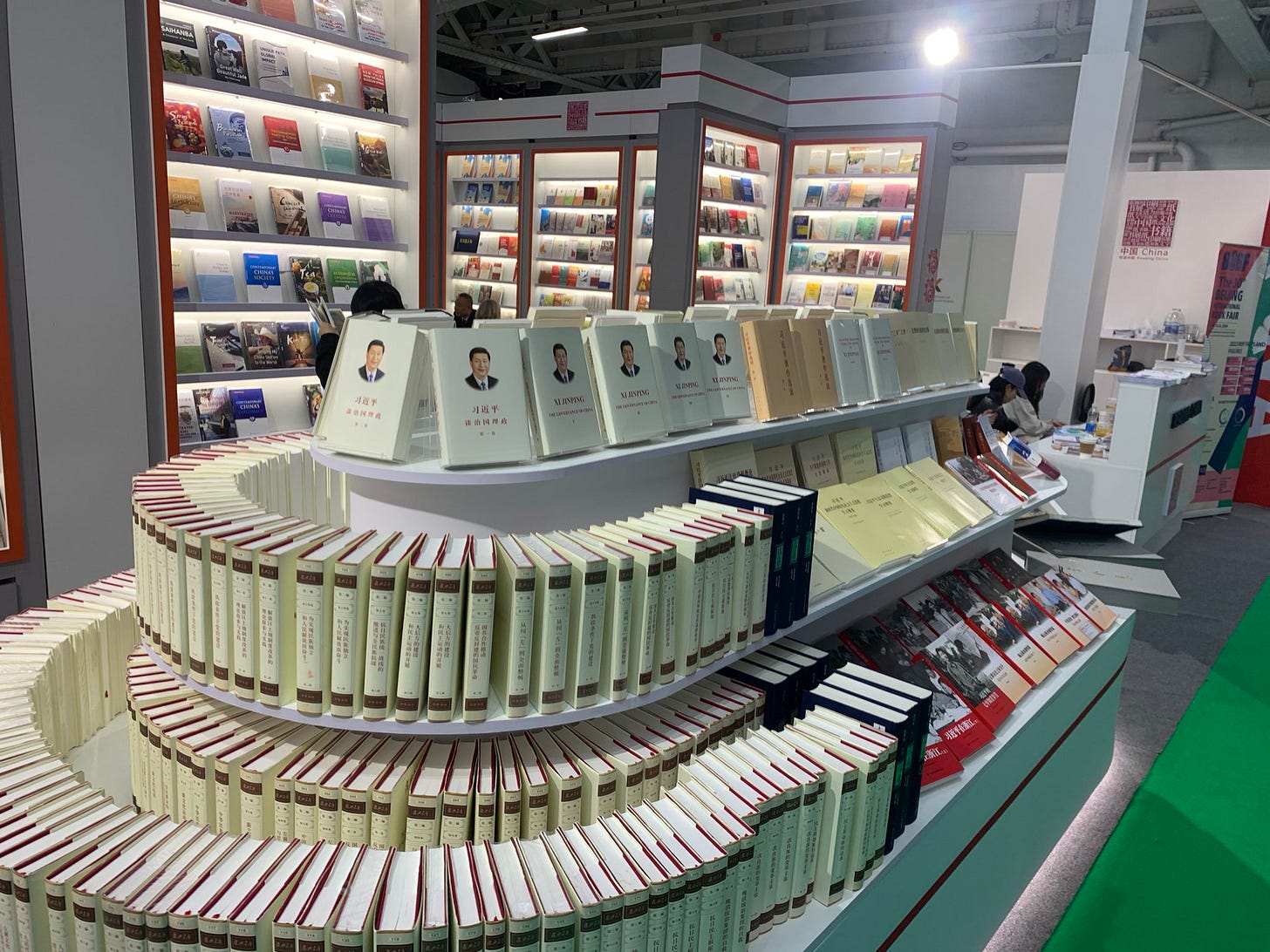

Amid the bustle of publishers wheeling and dealing for the latest hot titles at the London Book Fair in March, China’s offerings were a pallid sight.

State news agency Xinhua painted it as a roaring success — a “crucial” bridge for academic and cultural exchange, forged by over 3,200 titles on Chinese culture, history, society, and politics. But far from a bridge, what actually awaited anyone interested in books from China was a wall — one made entirely of Xi Jinping’s smiling face, staring out from the front covers of his ubiquitous Governance of China series.

Visitors to the book fair were less impressed by the sight than the editors at Xinhua. “Excited to see the Chinese state publishers had a range of thrilling new content to offer,” quipped Paul French, the author of bestseller Midnight in Peking and a scout for Chinese titles for Bloomsbury Publishing.

In a way, the display in London should not come as a surprise to anyone. “Chinese publishers are in some ways the publishing wing of the Chinese Communist Party,” explains Jo Lusby, the former CEO of Penguin Random House North Asia. But she hastens to add that this control over publishers doesn’t mean their titles are “all rubbish.”

“Chinese publishers are the publishing wing of the Chinese Communist Party.”

Many are well-written and apolitical, but what gets pushed internationally is another matter. These publishers “are driven by political imperatives and not the needs or demands of overseas markets” when exporting abroad, Lusby says, leading to the lineups of nothing but Xi.

At a time when fiction in translation is a growing market trend among young readers in the West, creative works translated from Chinese might be a genuinely humanizing force, telling diverse stories that engage foreign readers. But in a push to accommodate Xi Jinping’s narrow vision of “telling China’s story well” (讲好中国故事), a policy whose goal is to create a favorable image of the CCP and the raise China’s “discourse power,” Chinese publishers seem intent on gagging the country’s most compelling storytellers.

Despite such challenges, some publishers are trying to seize upon this trend, translating literature they consider the best China has to offer. But can they completely break free from the Party’s shackles, while also navigating the perils of a cutthroat, competitive market in the West?

Telling Whose Story Well?

Since Xi Jinping outlined the concept in his address to the National Propaganda and Ideology Work Conference in August 2013, “telling China’s story well” has been at the heart of Beijing’s strategy for external propaganda. That same year, after a visit from the country’s top propaganda official, the president of the state-backed China Publishing Group (CPG) signaled that state communication goals took priority over smart commercial decision-making when he said in an internal speech that CPG must increase book exports abroad, “in order to enhance the country’s discourse power and cultural soft power.”

Responding to this demand from the top, government bodies and publishers offered a series of grants to provide funding for the translation of Chinese titles. The assumption seems to have been that, if enough money were spent, Western readers would come running. “I once had a contact from a senior government official,” recalls Lusby, “who posed the purely philosophical question, ‘If I gave you a million US dollars, could you get a book onto the New York Times bestseller list?’” The official may have been posing a hypothetical, but the question in many ways epitomizes the focus at the top on throwing money at the question of impact.

More than a decade on, it doesn’t seem to be working — and a closer look at the titles put forward for translation offers some clue as to why. In 2017, state-owned publishers were interviewed by the CCP-led China Writers Association (中國作家協會) about which books they were promoting abroad. All of the titles in translation listed were about Xi Jinping’s political thought, poverty alleviation, ancient Chinese culture, or the war of resistance against Japan.

“These books are not likely to turn up on any kind of bestseller list abroad,” says Lusby, adding that publication abroad is often primarily a way to demonstrate publishers’ political credentials to the Party — to “tick the box.”

Translated titles pushed by government grants are of “questionable” quality and “ill-suited to the UK market,” agrees Ying Mathieson, the owner and Chief Publisher of UK-based Sinoist Books, an independent publishing house specializing in works translated from Chinese.

Not Banned, Didn’t Read

Across the board, China books — particularly those in translation — have become a tough sell among Western readers. Author Paul French attributes this to several factors, including poor knowledge of China and a distaste for its politics, which he sums up as: “little travel [to China], reduced academic enrolment in Chinese studies, and just a general disenchantment with Xi-land.”

As attitudes toward China have hardened, the types of stories that do sell tend to conform to certain Western prejudices about the country. Literary translator Dylan Levi King noted in 2020 that titles selected by Western publishers bear no resemblance to what is currently popular among Chinese readers. Indeed, being banned in China — and therefore inaccessible to readers there — “remains a major selling point,” he wrote.

“The assumption can be that those who don’t openly challenge China’s authoritarian system from within are apparatchiks, not artists.”

In her book The Subplot: What China is Reading and Why It Matters, arts journalist Megan Walsh says Western readers tend to have “unrealistic political expectations” of what Chinese authors can and cannot write about, and therefore assume that what has been blacklisted is likely more worth their time. “The assumption can be that those who don’t openly challenge China’s authoritarian system from within are apparatchiks, not artists,” she writes.

Part of the problem is that major UK publishers rarely go for Chinese translation, says Mathieson, dissuading them from exploring beyond politically sensitive topics. She estimates large publishing houses like Penguin Random House will gingerly attempt a Chinese fiction translation once every four or five years. Some will not commission again when they discover Chinese fiction is not profitable. “All the learning that the team made would then be lost as they are shuffled to other projects,” she says.

All this comes at what could otherwise be a golden opportunity for the genre. Fiction in translation has been making steady inroads into English-language readerships. Almost half of all sales of translated fiction in the UK come from readers under 35, representing a long-term market. And Japanese and South Korean authors have already seen significant success among these demographics, both through the grassroots popularity of authors like Han Kang and Haruki Murakami as well as the countries’ own government-funded translation programs.

Until recently, it even looked like China could follow in their footsteps. The 2010s saw a steady rise in Chinese fiction being translated into English, with titles from Western publishers tripling within just six years from 2013 to 2019. These began to level off in the last two years studied, however.

Despite the immense resources China has thrown at translating titles and promoting them overseas, its performance has been lackluster. In 2022, Chinese titles ranked tenth for the best-selling foreign language fiction titles in the UK. Japan, first.

Today, that downward trend seems unrelenting. At the Frankfurt and London book fairs over the past two years, there were “not a lot of books on social issues or literature” compared to before the pandemic, notes Xinran, a Chinese journalist and author now based in the British capital.

Caught In-Between

Caught between Western publishers, with their well-worn preconceptions, and the politics-first approach of state-backed PRC publishers, are independent operations like Sinoist and Astra Publishing House, which is owned by the Beijing-based Thinkingdom Media Group.

Thinkingdom translates Western classics into Chinese and vice-versa. The company, which established a US branch in 2020, has a well-connected stateside publishing team that looks beyond just Chinese titles, translating books from all around the world. They have translated Chinese works that garnered reader interest within China itself, such as a collection of poems from Yu Xiuhua (余秀华), a rural mother with cerebral palsy whose sexually charged poem “Crossing Half of China to Sleep With You” went viral online.

But Astra is the exception that proves the rule. “Of all the PRC publishers that have tried to go global, they are the only people who have done it in a truly commercial way,” says Lusby.

Sinoist Books, too, have broken the mold when it comes to the credible promotion of Chinese fiction. They went public in 2019 as the fiction arm of academic translators ACA Publishing, which was founded in Beijing but relocated to London in 2007. Paper Republic, a UK-registered charity that promotes Chinese literature in translation, credits them with a quarter of all the Chinese fiction published in English last year. Their work has earned them a grant from the publicly-funded charity Arts Council England totalling £50,000 a year until 2026.

Their mission is two-fold, according to Ying Mathieson: to help members of the Chinese diaspora who only know English to better understand their heritage, and to “promote a greater understanding of the Sinophone world through its literature.” They have turned out novels from highly-respected contemporary authors like Jia Pingwa (贾平娃) and Raise the Red Lantern author Su Tong (苏童).

Black and White and Grey All Over

In order to remain profitable and tell the stories they believe in, however, Sinoist Books has had to operate in a gray area. The publisher mostly translates works by authors who are members of the Chinese Writers Association (CWA), which operates under the auspices of the state-run China Federation of Literary and Art Circles.

Journalist Megan Walsh calls the body a “creaky old boys network” rather than strict ideological gatekeepers, however. Membership requirements focus on how much the writer has published and whether they have contacts with existing members, rather than political bonafides. Members even include contentious writers like Fang Fang (方方), a critic of the CCP whose latest work, the explosive Covid-19 memoir Wuhan Diary, was — as it happens — banned in China.

The CWA is a broad tent, but that doesn’t mean it operates independent of the Party’s agenda. It has launched a “China Readers’ Literature Club” to develop audiences for Chinese authors, with Sinoist as their UK representative.

At the 2021 launch of its “China Readers’ Literature Club,” CWA President Tie Ning expressed hope the initiative would allow literature to foster empathy in readers and to “explore another emotional world” — but the same address also contained a litany of Party rhetoric, like compelling readers to realize that they are “part of the community of common destiny for mankind,” a foreign policy phrase for Xi Jinping’s world vision. Sinoist is listed as the Club’s UK representative.

Communist Party mouthpiece the People’s Daily has reported positively on how these groups spread awareness about China abroad, while other CWA-led projects like the Belt and Road Literary Alliance show the group is keen to exploit intersectionalities between China’s soft and hard power.

For Mathieson, the CWA is an important partner that helps them discover interesting new titles, as well as a networking forum to connect with authors and editors. After all, says Mathieson, it is the country’s foremost network for writers, offering “a full range of representation of the literary output of China.” It is also almost impossible to avoid: “Every author working in China today,” she says, “is tied to the CWA to some degree.”

“Every author working in China today is tied to the Chinese Writers Association to some degree.”

Working extensively with Chinese publishing houses also demands that foreign partners accept that content must be palatable to the Party. “Everything in China has gone through some sort of filter just by dint of the fact that it has been published in China,” says Lusby. She adds, however, that there is not as much micromanagement in Chinese publishing houses by the Party-state as Westerners tend to think.

Sinoists’s parent company ACA has also carried material that the government is pushing abroad for political ends. Take a book like Nanjing 1937: Memories of a Massacre for example. Published by ACA in 2020, it documents the Imperial Japanese Army’s atrocities in the occupied Chinese capital in 1937, and was shortlisted for the 2015-2018 Silk Road Book Project then awarded by the State Administration of Press, Publication, Film, and Television (SAPPRFT). One website linked to China’s Ministry of Culture claims the book was chosen by SAPPRFT in 2014 as a priority topic for “cultivating and implementing socialist core values.”

On Borrowed Time?

Sinoist reports they are now reliably selling out their print runs. But these remain small, ranging from 500 to 1,000 copies. The UK’s Companies House listed ACA as having debts standing at £145,000 in 2023, roughly three times the company’s current assets. Mathieson agrees that the business is a “gamble,” given that the costs of translating, printing, and marketing a book are all made without knowing whether the investment will be recouped in sales. “All we can do is offer the best possible platform so that the chance of success is as high as possible,” she says.

Some of the company’s funding sources have been controversial. Before they obtained their Arts Council England grant, they relied to some degree on funding from the Chinese government, offered for printing small batches of political books under the ACA brand. Sinoist confirmed this when asked for comment, but noted that the money provided is generally not even sufficient to cover related costs. Daniel Li, Sinoist’s marketing officer, told Lingua Sinica that Chinese grants covered only part of the translation costs in addition to publicity costs. “All other costs incurred — rights, printing, editing, proofing, marketing, book cover design, and a multitude of other sundries — require the input of the publishing house,” he said.

Diversifying funding sources has been one way for Sinoist to deal with the unpredictability of the publishing business. Mathieson says they are looking for support from both inside and outside the PRC, but that keeping their heads above water sometimes requires digging into personal savings. It remains to be seen if their approach of straddling both sides will work as a business model. The challenges are immense, according to Lusby. “They are publishing hard-to-publish Chinese literature and committing to it,” she says, “but commercially it is a very tough road.”

For her, there is more promise in an “increasing number” of Chinese writers based abroad, writing in English. They can fulfill readers’ appetite for Chinese stories with none of the off-putting Party strings attached. Writers like RF Kuang, who was born in China then grew up in the United States, “are succeeding in mainstream fiction at a level that we have not seen among mainland writers translated from Chinese,” she says.

For writers based in China and writing in Chinese, however, there is no guarantee that telling their own stories well will be enough to reach readers behind the wall of political and market demands.

Very good.

This has been going on for some time at the London Book Fair, of course. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/mar/20/london-book-fair-chinese-writers