Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 9 January

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

And a belated merry Christmas and happy new year to all our subscribers who celebrate. This is our first newsletter of 2025, after a brief hiatus for the holiday season. While we were taking some time off, PRC propagandists were hard at work, driving a midwinter surge in international communication centers (ICCs) that we explore in depth in Going Global below.

Here in Taiwan, it also proved impossible to escape the reach of Chinese state-run media. On New Year’s Eve, I once again joined the throngs of people ringing in 2025 at Taipei 101. After the countdown and spectacular fireworks display, however, many were shocked to see China’s state-run broadcaster CCTV play on the big screen nearby. This misstep has set off a political scandal in the capital, with the city’s government — run by the more China-friendly KMT and a mayor who claims to be descended from former dictator Chiang Kai-shek — blaming the contractor, local TV station TVBS. Incidentally, we have covered some of their history vis a vis China and Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing broadcaster TVB in our “Media in Focus” series.

TVBS says it was a simple technical oversight: a technician’s laptop was running YouTube on autoplay, and when the main show stopped and the feed switched to backup, CCTV happened to be streaming. But it’s still a fresh reminder of how raw nerves are about PRC media encroachment. The news never stops — and neither does news about the news.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

GOING GLOBAL

New Year, New ICCs

Will leopards and postcard scenery be enough to earn China’s leadership greater “discourse power”?

As the year drew to a close, local governments across China appeared to be in a hurry to establish new international communication centers (国际传播中心), or ICCs, at the city and county level. ICCs, as we’ve written about since they began to emerge in 2018, are remaking the CCP’s overall propaganda matrix, mobilizing resources beyond traditional, state-run media outlets to enrich and amplify the Party’s messaging worldwide. ICCs were first founded by provinces but have since trickled down to cities, counties, and even lower levels of government.

While we were taking a break over Christmas, eleven new local ICCs opened their doors, demonstrating increased localization and specialization of the system as well as its potential drain on tight local government budgets. Jilin province reportedly spent millions on camera equipment to get snaps of the endangered Amur leopard and Siberian tiger, but it’s anyone’s guess how its new “Northeast Tiger and Leopard Culture International Communication Center” will recoup this investment — particularly when other ICCs have been struggling to turn a profit

As nearly every PRC province and region founded its own ICC over the past few years, far-western Xinjiang has been a late adopter. On December 29, Xinjiang’s branch of the Cyberspace Administration of China (网信新疆) finally announced the formal launch of the Xinjiang International Communication Center (新疆国际传播中心). The announcement framed the center as Xinjiang’s "principal window of external communication," promising it would “tell the story of Xinjiang in the New Era well through many forms and channels in international society." For a glimpse of what this may look like, we can turn to some of the videos the center released in a 2023 test run. These featured the standard fare of postcard scenery, exotic ethnic minorities, and bedazzled foreigners. Now known for subjecting those minorities to crimes against humanity, Xinjiang needs more than anywhere else to refurbish its reputation — but it’s unclear whether this revolution in propaganda production will simply give us more of the same.

TRADING PLACES

Hong Kong’s State-Media-to-Government Pipeline

Wu Ming (吳明) was the executive chief editor of the state-run Wen Wei Po (文匯報) newspaper until he resigned unexpectedly last year. Now, he’s a Senior Special Assistant to Hong Kong’s Chief Secretary for Administration, Eric Chan Kwok-ki (陳國基). In his new role, Wu — who also worked for China’s state-run Xinhua News Agency before relocating to Hong Kong — will specialize in researching policy in the PRC, and will advise Hong Kong’s second-highest government official on how to speed up the territory’s further integration with the mainland.

His appointment was made quietly and only caught the media’s attention after they noticed his name in the government’s telephone directory. The government insists that Wu, a 40-year veteran of the local and mainland media scenes, was simply the best man for the job. But when Ming Pao (明報) enquired whether there was an open recruitment process for the position and asked what Wu’s government salary is — usually a matter of public record — their questions went unanswered.

It’s not the first time a state media staffer has entered government in Hong Kong. In fact, we documented a few other cases in our “Media in Focus” investigations into former Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying’s Looop Media and pro-establishment broadcaster TVB. But it’s still a growing trend that’s worth looking out for. As media scholar Francis Lee explained in his recent interview with InMedia (see Spotlight), media influence in Hong Kong can be hard to gauge. It’s certainly not about how many readers you have — if it were, wildly popular outlets like Apple Daily and Stand News would still be around, and outlets like Speak Out HK that few read and even fewer trust would be irrelevant. Instead, it’s more often about who your readers are. Wen Wei Po doesn’t need support in the streets if it has it in the halls of power.

CONTROVERSIES

Testing Taiwan’s Media

An influencer lays a trap for mainstream media outlets

In what he claims was a ploy to unmask poor professionalism in Taiwan’s media, Taiwanese YouTuber Su I-fei (蘇裔非) posted a staged video last month to Threads that purported to show a physical altercation between youth on the Taipei subway, or MRT. Su’s hypothesis was that the media in Taiwan, known for their interest in conflict and sensationalism, would pick up the fabricated video and report the story without attempting to verify its accuracy.

Su seems mostly to have been right. Several major media outlets, including the pay television channel TVBS, CTV (中視), a station under the China Times Group, and CTi News (中天新聞台), a 24-hour online news outlet, all reported it without verification. Mirror Media (鏡週刊) was alone among outlets in seeking a response from Taipei’s Department of Rapid Transit Systems.

On December 27, Su posted a video to his YouTube account called “I Used Fake News to Fool Taiwan’s Media” (我用假新聞騙了台灣媒體) in which he detailed his experiment — which cost him a total of 3,500 Taiwan dollars to film — and called out media for their credulity and lack of professionalism in running the story without seeking to confirm the incident with the transport authorities.

But Su may not get the last laugh in this case. In response to media inquiries, police from Taipei’s Rapid Transit Division said that the fabricators of the video in question could be fined up to 30,000 NTD if a report was made to the police under Article 23 of the Social Order Maintenance Act, which includes under “Public Nuisance” the “spreading [of] rumors in a way that is sufficient to undermine public order and peace."

Legitimacy Lost

Taiwanese officials tell a mainland media outlet it is no longer welcome

Taiwan’s Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) said earlier this month that the country would bar the Strait Herald (海峽導報), a newspaper launched in 1999 by the official Fujian Daily Newspaper Group (福建日报报业集团), from stationing reporters in Taiwan due to its alleged involvement in "united front work" activities. MAC said the outlet could no longer be regarded as a "legitimate media platform" following its finding that the Strait Herald had interfered in Taiwan’s political elections by fabricating polling results.

Media in Fujian province have been under increased scrutiny in Taiwan in recent weeks following the release of a YouTube video on China’s “united front” tactics produced by Taiwanese rapper Chen Po-yuan (陳柏源) — who performs under the stage name Mannam PYC (閩南狼) — and another YouTuber, “Pa Chiung” (八炯). Going undercover to report on China’s recruitment of Taiwanese influencers, the pair obtained audio of Lin Jingdong (林靖東), a top official at the Strait Herald, suggesting to Mannam PYC that money might be provided for vote buying if he were to run for office in Taiwan.

According to this archived entry from China's Huaqiao University, which is run by the CCP's United Front Work Department (UFWD), Lin Jingdong is a member of the editorial committee (社委委员) of the Strait Herald, and first began working at the paper in 1999. The paper’s parent media outlet, Fujian Daily (福建日报), is the official mouthpiece of the province’s CCP committee.

"The media outlet has a clear nature of engaging in united front work targeting Taiwan,” MAC deputy head Liang Wen-chieh (梁文傑) said on January 2. “We believe the Strait Herald is no longer a legitimate media platform.”

The MAC announcement drew a swift reaction from China’s government, the Taiwan Affairs Office responding that the incident was "a slander against the legitimate reporting behavior of mainland journalists with unfounded accusations" and "a blatant reversal of cross-strait news exchanges." Taiwan’s China Times (中時新闻), an outlet under the Want Want snack food group that tends toward staunchly pro-China viewpoints, called the case a “demonization” of mainland media.

TRACKING CONTROL

Cutting Micro-Dramas Down to Size

Micro-dramas — TV series cut into short snippets of one to 15 minutes — are becoming a huge business worldwide. The global market for this new, bite-size format is said to be worth two billion dollars a year, with forecasts that this could double by the end of 2025. And that’s excluding China, which has emerged as a global leader in the production and consumption of weiduanju (微短剧).

With the PRC’s micro-drama market growing at a blistering 250 percent annually, bringing in some RMB 37.4 billion (5.2 billion dollars) in 2023 according to state media reports, the authorities are also acting quickly to figure out how they can control this new entertainment format and ensure it serves their interests. On January 4, the National Radio and TV Administration (国家广播电视总局), or NRTA, publicized its plan to create hundreds of short videos on Xi Jinping’s political thought — for example, by promoting his vision of uniting classical Chinese culture with the latest technology and teaching netizens about the benefits of Xi’s version of the rule of law.

The agency also announced that, over the coming year, it will draw up regulations for stricter micro-drama governance. An anonymous TV producer told the Global Times that this is because the format currently offers only “emotional value” rather than “promoting positive values” — a euphemism for Party values. Chinese micro-dramas have so far proven popular before within the PRC and beyond its borders, and the format has found a natural home on Chinese platforms like Kuaishou and Douyin. The industry’s new challenge will be how to preserve this early success while also pleasing censors and ensuring Xi plays a starring role.

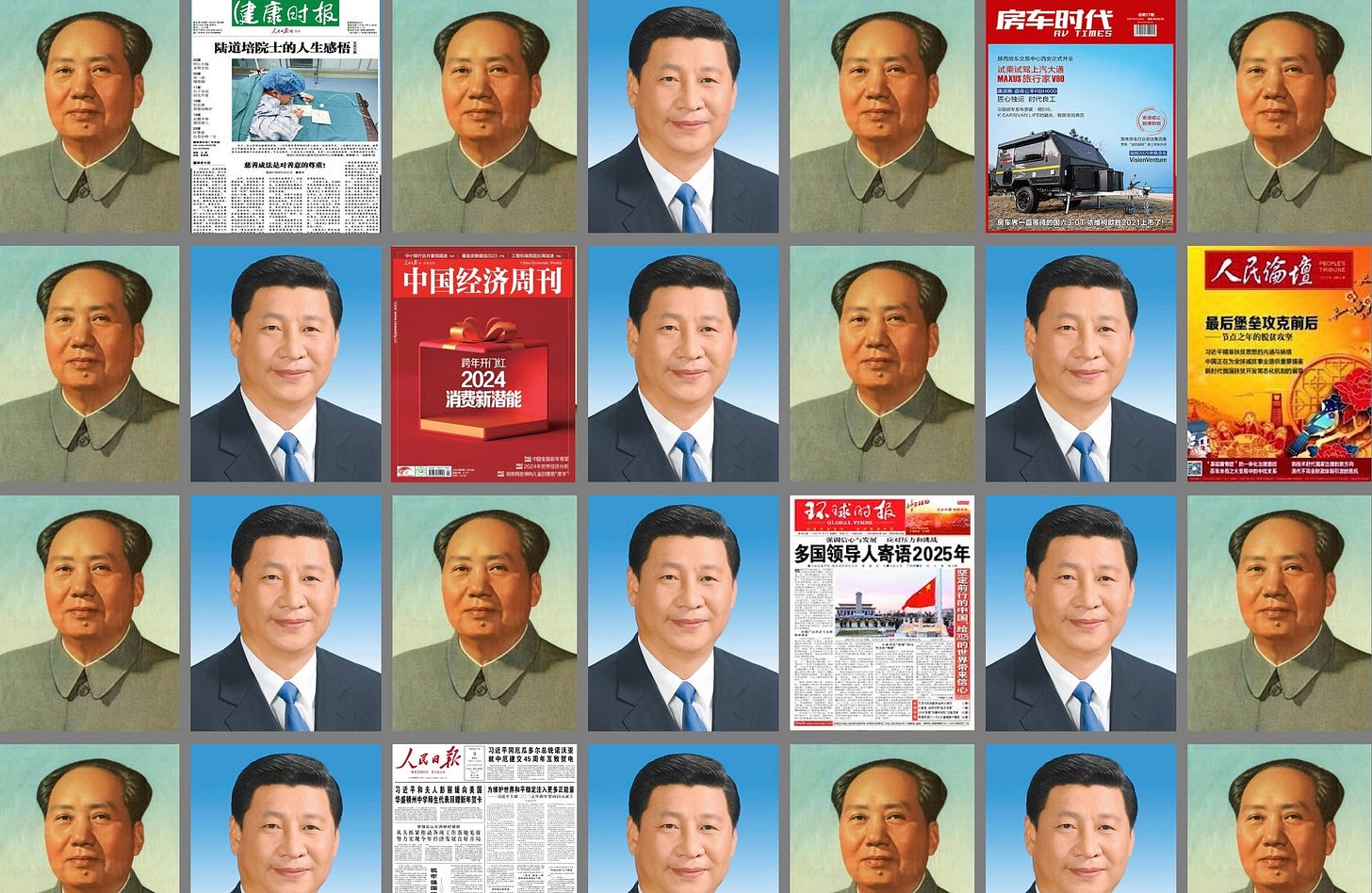

The Many Faces of the People’s Daily

Think “state media” in China and you’re likely to conjure an image of the People’s Daily (人民日报). The daily newspaper, directly run by the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) Central Committee since 1948, prides itself on being the “mouthpiece” (喉舌) of the Party leadership. And a role this important demands regimentation and structure: a staid face to communicate the thoughts of the CCP core.

But while it is the most representative of the Party leadership, the People’s Daily newspaper, first launched in 1946, is not the only face of this Party-run media group. The paper’s parent organization, the People’s Daily Press (人民日报社), is in fact a sprawling media empire. The group oversees a portfolio of 34 periodicals as well as a wide array of newer digital products. It runs a health magazine, a history journal, a newspaper for gearheads, and even the RV Times (房车时代), a periodical for recreational vehicle enthusiasts.

In CMP’s latest “Media in Focus” investigation, contributor Bertie Lyhne-Gold takes a look behind the curtain of the People’s Daily empire. Read the full article here.

SPOTLIGHT

Making Waves

Charting the rise, fall, and rise again of Hong Kong’s once-vibrant, always-resilient online media

In an interview with Hong Kong’s InMedia (獨立媒體) last week, Professor Francis Lee at the Chinese University of Hong Kong’s School of Journalism and Communication offered characteristically insightful reflections on the development of online media in Hong Kong.

Lee told the digital news site that the sector’s history can be divided into three waves. The first wave emerged from the historic July 1 march against national security legislation in 2003 and was led mainly by social activists. The protest — the biggest post-handover Hong Kong had ever seen — was a political awakening for many, and many activists dissatisfied with traditional media set up their own outlets. InMedia itself was a product of this first wave. While their audiences were initially small, the advent of social media platforms like Facebook offered new avenues to disseminate their work. Popular protests to protect the historic Queen’s Pier in Central and to oppose high-speed rail development helped to propel this first wave.

The second wave, conversely, was led by professional journalists who made the leap from traditional to digital media. Beginning around 2012, it was more in line with the practices of traditional media, but at the same time sought to do things differently: to cover stories and platform voices overlooked by the big outlets. The latest, ongoing wave, Lee says, began in 2022 in the aftermath of the national security law imposed by Beijing. Although 2019’s anti-government protests saw online news become more important than ever for live, on-the-ground coverage, the crackdown forced the biggest and best-known outlets to close.

As the dust has settled in national-security-era Hong Kong, new outlets have sprung up — like The Collective (集誌社), Channel C, and The Witness (法庭線). As Hong Kong journalists have relocated abroad, we’ve also seen a proliferation of exile and diaspora media outlets like Photon Media (光傳媒) here in Taiwan and Green Bean (綠豆) in the UK. The former need to tread far more carefully than the previous two waves did to ensure their survival in the new Hong Kong. They each take a different approach but are linked by certain commonalities like aspirations to continue performing a supervisory function and to pass down local culture and social values.

If you want to hear more from Francis Lee on how local journalists have been adapting, check out the interview I did with him last year on “The Risky Business of Hong Kong Journalism.”

United Front Tactics in the Crosshairs

“Spiritual tours” to push the China narrative in Taiwan

Early last summer, YouTuber “Weigo” (瑋哥), real name Chen Ruiwei (陳睿瑋), got a message from a travel agent friend in Taiwan, asking him if he fancied a free trip to the scenic Wuyi Mountains (武夷山) in China’s Fujian province, airfare and accommodation inclusive.

For Chen, an alumnus of the hit online group Wackyboys (反骨男孩), the offer was presented to him as a simple business deal, no different from previous invitations to fly to Thailand to shoot restaurant promotions. What he joined, along with more than 10 internet celebrities and other participants from Taiwan, was billed by organizers as a "spiritual tour" (靈感之旅). Never did he imagine that because of this trip, he would be branded in Taiwan as "doing propaganda for [Communist] bandits" (為匪宣傳). He was among those outed by Taiwanese influencer Potter King (波特王), whose video on China’s “united front” tactics has been a chart-topper for weeks in Taiwan — and soon more footage was dug up showing Chen and others on PRC media.

Recently, YouTubers Pa Chiung (八炯) and Chen Po-yuan (陳柏源) — who raps under the stage name “Mannam PYC” (閩南狼) — collaborated on an undercover documentary to talk to the officials from the united front department in Fujian’s Wuyi Mountain, which confirmed that the Chinese Communist Party has been hosting Taiwanese YouTubers. The trend was also the subject of an in-depth report by Taiwan’s CommonWealth (天下) magazine at the end of December. It details how the approach was ignited by official panic over the 2014 Sunflower Movement, when young Taiwanese occupied the country’s legislature to stop the rushed passage of a trade pact tying Taiwan closer to China. Since then, PRC authorities have been vying to win over Taiwan’s youth by co-opting traditional celebrities and new online influencers.

Watch the ongoing YouTube documentary series and read CommonWealth’s article for more.

A Vicious Cycle in the Bureaucratic Labyrinth

It’s time to talk about Taiwan’s civil service

In November last year, a 39-year-old civil servant working in Taiwan’s Ministry of Labor committed suicide due to prolonged workplace stress, exposing serious structural problems within Taiwan's civil service system. In an in-depth investigation published on January 3, The Reporter (報導者), one of the country’s leading independent news outlets, explored the full range of these problems — including staff shortages and excessive overtime. The outlet spoke directly with numerous sources inside the civil service.

According to 2023 data, agencies under Taiwan’s Executive Yuan, the country's highest administrative organ, have a vacancy rate of positions of 29.5 percent, meaning that nearly a third of positions remain unfilled. Sources interviewed by The Reporter told the outlet that it was standard for them to work as late as 9 PM, and that work often continued after they returned home. The civil service system, experts said, is caught in a vicious cycle in which staff shortages lead to overwork, which results in further resignations that exacerbate vacancies. Incompetent supervision and chronic bullying were also cited as problems in the report.

“I think the civil service has been squeezed to the point where . . . you [our supervisors] pile on trifling matters, add on more crap, and together we quickly produce a bunch of stuff,” one civil servant damningly told The Reporter.

Tribute to a China Watcher

When Benjamin Kang Lim (林洸耀), one of the longest-serving correspondents in China, passed away on May 21 last year of acute pancreatitis, his loss was mourned by journalists and China scholars alike. Australian Sinologist Geremie Barmé called Lim "an insightful analyst and commentator in the best tradition of China Watching." John Ruwitch, a former colleague of Lim’s at Reuters who is now with NPR, called him “driven, principled, fair and, most of all, relentless in his pursuit of scoops.” During a journalism career spanning four decades, Lim broke many important China stories, including the death of Deng Xiaoping in 1997 and the rise of Xi Jinping within the CCP ranks ten years later, in 2007.

In a special tribute to Lim published on December 31, more than seven months after his death, Initium Media (端傳媒) took an in-depth look back on his life and work, praising his penchant for both news scoops and “original political observations.” Unlike many of the tributes written about Lim in May last year, the piece, written by James Wang, included details from Lim’s copious reporting on China. It noted, for example, how Lim had shrewdly observed Xi Jinping's attendance of funerals in 2015 for senior political leaders from both the left and right factions in 2015 — reading signs of Xi's efforts to bridge divides and consolidate power ahead of the 19th National Congress of the CCP. It also suggested that Lim’s views had often "differed from the mainstream discourse of foreign media" on China.

NEWSMAKERS

Universal Daily News Stops the Presses

A farewell to Thailand’s second-oldest Chinese-language newspaper

The Universal Daily News (世界日報), long Thailand’s largest Chinese-language daily newspaper by circulation, announced with a short front-page article on December 31 that it was closing its doors on January 1. Headquartered in Bangkok, the paper recently reported 50,000 daily readers of its print edition and more than 200,000 daily online readers. But the outlet, citing bottom-line pressure stemming from the pandemic that had impacted traditional media worldwide, and the growing popularity of social media for news consumption, said in its notice that limited funds now made it impossible to continue operations.

The paper was founded in 1955 by Thai-Chinese bank mogul Chin Sophonpanich (陳弼臣). News coverage at the outlet spanned business, politics, society, and tourism in Thailand. In 1986, it was purchased by Taiwan’s United Daily News Group. With a history spanning nearly seven decades, it was the country’s second-oldest Chinese-language newspaper.

In its farewell message, the Universal Daily News expressed gratitude to its readers and emphasized that suspending its print edition was not the end of its mission. "We believe in Chinese culture,” the paper said. “It will still shine brightly in Thailand, and the suspension of the Universal Daily News print edition will not be an ending."

REACTIONS

A Taiwanese Take on American Violence

As Luigi Mangione goes to trial for the killing last month of healthcare CEO Brian Thompson, the case continues to stir debate in the US and abroad. Many have celebrated the New York City shooting as an act of righteous violence against America’s broken healthcare system and the widening gap between rich and poor. Others have condemned recourse to violence regardless of the cause, and have lamented the poor values represented by Mangione’s many admirers.

In Taiwan’s United Daily News (聯合日報), or UDN, freelance contributor Da-Wun Sie (謝達文) writes that reactions to political violence tend to follow a script in the US. Politicians at every level claim that such actions do not represent American values and that social ills can be remedied through the democratic process. But Sie calls this an act of “political and historical amnesia,” neglecting the part that violence has always played in US politics, from presidential assassinations to the January 6 Capitol riot. The recent resurgence in politically motivated violence represents the recurrence of a familiar cycle rather than the emergence of a new phenomenon, he says.

“The unfortunate thing,” he concludes, “is that such violence might represent you [Americans] perfectly.” The writer’s dismay is doubtless shared by many international observers — but it also dovetails nicely with the “pan-Blue” political camp traditionally championed by the UDN, which in addition to taking a more positive view of the PRC has also promoted “US-skepticism” (疑美倫) and criticized the ruling Democratic Progressive Party for leaning too heavily on ties with the US.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

With Chinese Help, Pakistan Builds Its Own “Great Firewall”

China presents itself as a model for the developing world. And as it cements its position as a technological as well as economic and political powerhouse, there is the possibility that more closed or outright authoritarian countries will follow the PRC playbook for tightly controlling and monitoring its citizens’ behavior online — a set of restrictions broadly known as the “Great Firewall of China.” Pakistan, one of Beijing’s oldest and closest friends, looks to be following in its footsteps faithfully. The country is deploying Chinese tech to build what some call a new, nationwide “firewall” of their own, according to reporting by Al Jazeera. This will allow authorities to monitor online traffic and regulate the use of popular apps with greater control than before.

For more information on how this might affect press freedom and digital rights in the country, we spoke with Dr. Sriparna Pathak, an associate professor at the Jindal School of International Affairs at O.P. Jindal Global University in Haryana, India.

Lingua Sinica: When were Pakistan’s internet controls first introduced, what kinds of content have they targeted, and are we now seeing this restriction tighten?

Pathak: Pakistan has emerged as a country reeling deeply under Chinese influence, be it in the economic, political, or technological realm. In February, Pakistan banned X citing national security concerns. Now that it is deploying Chinese technology to build a national internet firewall, authorities will be able to monitor online traffic and regulate popular apps' usage with greater control than ever before. Like in China, it will also slow down the internet.

Messaging app Telegram and peer-to-peer sharing client μTorrent are permanently blocked in Pakistan, and Facebook and YouTube have been temporarily blocked many times. Generally, internet filtering in Pakistan has been inconsistent and intermittent. It is aimed at targeting pornography, homosexuality, content deemed to be a threat to national security, and religious content considered blasphemous. The country has also blocked access to websites critical of the government or the military. With the new firewall, blocking dissent on any or all of these platforms will get much easier. It also shows that Pakistan is willingly following the Chinese model of censorship and internet governance.

Pakistan is willingly following the Chinese model of censorship and internet governance.

LS: What is the current state of press freedom in Pakistan?

Pathak: In 2024, Pakistan dropped to 152 out of 180 countries in RSF’s Press Freedom Index. Censorship and the killing, enforced disappearance, and arbitrary detention of journalists are only the tip of the iceberg. Pakistan is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for media personnel and the level of impunity for murders is appalling. Given the continuing, contentious political landscape, and the copying of Chinese methods of digital governance, things are only going to get worse, even as new media outlets emerge.

LS: In addition to Pakistani media, who else will “Great Firewall”-style restrictions affect?

Pathak: Both journalists and ordinary citizens will be adversely affected by such a “Great Firewall.” Even without it, the murders of journalists, and the jailing of web users who merely express themselves online have become commonplace in Pakistan. With the Great Firewall, monitoring becomes much easier and will lead to more dangers for civil society.