Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 5 September

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

Another newsletter, another dark day for the press in Hong Kong. Last time, it was a new low for the city’s press freedom score. The time before that, it was the Wall Street Journal becoming party to the government’s press crackdown by firing a reporter elected to lead the local journalists’ union.

This time, it’s a court verdict that sets a troubling new precedent. Last Thursday, two former senior editors at Stand News (立場新聞) were found guilty of sedition over opinion pieces the pro-democracy online outlet ran over several years. Stand’s former editor-in-chief Chung Pui-kuen (鍾沛權) and ex-acting editor Patrick Lam Shiu-tung (林紹桐) were both charged under a colonial-era law that hadn’t seen the light of day for decades.

The trial was described as “a litmus test for press freedom in the city.” If that’s apt, the results couldn’t be clearer — or more damning. Even more than ever before, journalists in the city will be watching every word they and their columnists say. It’s important, though, that we don’t simply write off Hong Kong and declare once and for all that journalism in the city is dead. Things are bad but they can — and likely will — get worse. Our capacity to still be shocked when that happens matters. Keeping it alive means taking stock of what is and is not possible there, and supporting the individuals and organizations who continue to report on and from Hong Kong.

We’ll certainly continue doing our bit by monitoring the space closely and pointing our readers both to dark new developments like this as well as bright spots in regional media. We hope this newsletter, like the rest of our work, helps you get a clearer lay of the land.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

RED LINES

A Media Frenzy for China’s African “Friends”

China is keen to demonstrate its pull in the diverse region, while visiting leaders have their own agendas.

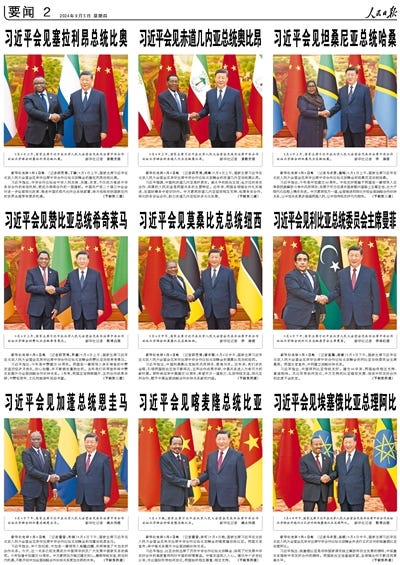

As African statesmen landed in Beijing this week for a major summit between Chinese and regional leaders, they also landed on the front pages of the People’s Daily. On Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, the official Communist Party “mouthpiece” (喉舌) — their term, not ours — dedicated its entire front pages to the meeting. Elsewhere throughout the newspaper, full-page spreads were also dedicated to features like "Stories of Xi Jinping and His African Friends" and "China-Africa Cultural Exchange in the New Era.”

The Forum on China-Africa Cooperation is being billed by international media as an opportunity for China to showcase itself as a lead partner for the continent, expanding its influence in the region as it competes for global leadership with the Western world. The coverage it’s been receiving in state media is a sure sign that the CCP attaches as much or more importance to the summit as this reporting suggests.

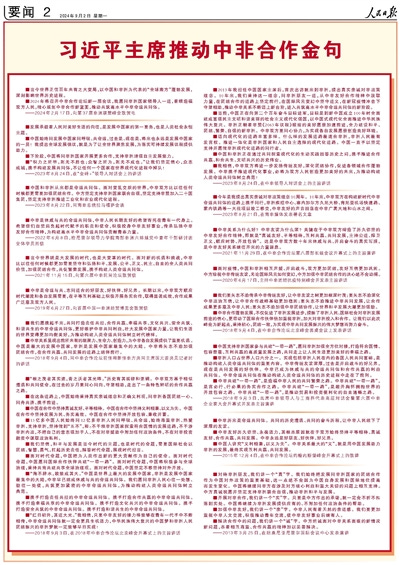

On Monday, before the forum kicked off, A2 was filled from end to end with “golden words” (金句) from Xi on Africa. Highlights include “China and Africa have become a community of shared destiny,” “China and Africa have always been a community of shared destiny,” and “the new phase of building a high-level community of shared destiny between China and Africa has begun.” The phrase “community of shared destiny,” a keystone of Xi-era foreign policy, occurs 28 times on the “golden words” page. The spread reads like a greatest-hits collection of Xi-era tifa (提法) — Communist Party sayings that mean little to those who don’t swim daily in such esoteric language.

Another recurring theme among the Xi-isms was the PRC’s indefinite claim to be a member — indeed, a leader — of the developing world. “China has always been and will always be a member of the developing world!” it quotes Xi as saying. “Always” is a long time, especially for an economic giant like China. As CMP Director David Bandurski wrote last year, this provides benefits both real and rhetorical. Always being a developing country means China will always receive (undue?) preferential treatment — including billions in World Bank loans — by virtue of its designation as a “developing nation.” As its inclusion here shows, it also enables the PRC to claim to represent the majority of the world’s countries, no matter how much richer, stronger, and more domineering it grows.

Beyond the rhetoric, of course, there are real desires on all sides, and African leaders are in Beijing for their own reasons. Many see the benefits of closer cooperation. And with its economy flagging, China is surely keen to convince African leaders that they can anticipate loans and investment — if they buy more Chinese goods.

NEWSPAPER GAPS

In many Chinese dailies today, there are just echoes where the news should be.

As China-Africa coverage has flooded the party-state media in China this week, there is little news to be found at all. Most papers at the provincial and city levels merely imitate the People’s Daily. The exceptions, still, are the commercial spin-offs of CCP-run newspapers — known as “child papers” (子报) — which try to be more responsive to audiences. Here’s a rundown of six papers:

The CCP’s official People’s Daily, which defines the Party “news” of the day, runs only Xi Jinping headlines dealing with Africa. All literally begin with “Xi Jinping.”

Nanfang Daily, the official mouthpiece of the CCP Committee of Guangdong province, entirely mirroring the People’s Daily.

Southern Metropolis Daily, a commercial spin-off of Nanfang Daily, running front-page news about the “champions” of Shenzhen manufacturing, focusing on the local economy — with a far more colorful layout.

Guangzhou Daily, the official mouthpiece of the CCP Committee of the city of Guangzhou, entirely mirroring the People’s Daily.

Information Times, a commercial spin-off of Guangzhou Daily, running front-page news about about a typhoon due to make landing in the area tomorrow — seeking some local relevance.

Yangcheng Evening News, another paper under the CCP Committee of Guangdong province, which in the 2000s had a reputation for more freewheeling coverage, again completely echoes People’s Daily.

STORYTELLERS

In Taiwan, Anybody Can Be a Journalist

Citizen journalism can be a dangerous hobby in the Sinophone world. Citizen journalists (公民記者 or 民間記者) in China are regularly jailed for their coverage, which tends to buck against the Party-state’s official narratives. Zhang Zhan, a lawyer turned citizen journalist who reported from Wuhan in early 2020, was only recently released from prison for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble” (CMP Dictionary). Her current whereabouts remain unknown. Hong Kong’s national security crackdown has netted citizen journalists too — dubbed “fake” or “black” journalists (黑記) by local authorities. The city’s ongoing campaign against the Hong Kong Journalists Association has also hinged on false accusations that it abused its role as an official accreditor to protect anti-government “rioters.”

And what about Taiwan, the region’s only remaining free press environment where the Chinese language is dominant? Here, citizen journalism is not only permitted by the government but actively facilitated through publicly funded entities.

In a Lingua Sinica special tomorrow, we’ll take a closer look at PeoPo (公民新聞), Taiwan’s biggest platform for citizen journalism. Stay tuned!

SPOTLIGHT

In Taiwan, Nobody Wants to Be a Journalist

There was a time when news media was one of Taiwan’s most promising industries. As martial law was lifted and censorship came to an end in the 1990s, new magazines, TV stations, and broadsheets came thick and fast. In order to get the best talent, they also had to offer competitive salaries. For cub reporters, it was a halcyon age when every day felt like they were writing a new chapter in the young democracy’s history.

Those days are decidedly over. Now, according to a new piece by Initium Media, “no one wants to become a journalist” in Taiwan. The testimonials it presents from seasoned media professionals are damning. We hear from a professor at one of the country’s top j-schools who says they “can’t think of anything appealing” about the profession and “no longer has students worship at the altar of the Fourth Estate” — a grandiose vision of the journalist’s calling that in the past has enticed some young people to brave poor working conditions in exchange for a sense of mission.

These days, journalists in Taiwan must contend with poor wages, high pressure, and long hours. Starting salaries can be as low as NT$20,000 (US$623) a month — less than rent for a studio flat in Taipei — and annual leave, just three days. Days off aren’t really days off, either. Reporters often have to use these to conduct interviews and get chewed out by their bosses if something on their beat happens and they’re not around to cover it. I worked for a major Taiwanese outlet for most of my first two years in Taipei, and a lot of what I read in this article was uncomfortably familiar.

If you want to get an idea of why the media here is so troubled, definitely give the Initium piece a read.

The Dark Reality Behind Black Myth

Black Myth: Wukong (黑神話:悟空) has been the talk — and toast — of the gaming world since it dropped late last month. Following the events of the classic novel Journey to the West (西遊記), it’s been billed as a long-awaited triumph for the Chinese video game industry — its first truly international success. And the fact that Chinese mythology, history, and literature figure so prominently in the gameplay means that it is also being seen as a coup for Chinese soft power as a whole.

The game has not been without controversy, though. Singapore-based Initium Media (端传媒) published this in-depth piece about how concerns over sexism and gender discrimination have cast a pall over the game’s success. Reporter Allison Yang Jing (楊靜) provides a detailed account of recent events in this area. One of the most standout incidents was when Black Myth: Wukong’s lead developer Feng Ji (冯骥) made a series of statements online that made female gamers squirm. Thanking gamers for their support, he likened his excitement to being “licked to the point of erection” (舔到勃起).

While fans were reeling from this stomach-churning analogy, older comments from the game's art director Yang Qi (杨奇) also resurfcaced. “Forget about sissies,” he said, “gaming is for men who are restrained, angry.” Women, he implied, are too concerned with handbags and impressing their friends to excel at gaming. Behind the scenes, they clearly knew they had a potentially explosive controversy on their hands. When gaming influencers were given early access to Black Myth: Wukong, they were told not to mention news and politics, Covid-19, or “feminist propaganda” while reviewing the game.

All this is just the tip of the iceberg — if you want to know more, read the full article.

DID YOU KNOW?

Despite state media’s concern for Pavel Durov, Telegram has been banned in China for nearly a decade.

The arrest in France of Telegram CEO Pavel Durov has been big news globally since late last month. Like so many others, official PRC outlets have been covering the story closely. Official news agency Xinhua and the China Daily newspaper highlighted free-speech concerns around the arrest of the messaging app’s Russian-born co-founder. Pointing to the apparent inconsistencies in the West's free-speech advocacy is a tried and tested strategy for state media to undermine their critics. But it's also inconsistent with China's own stance on the app, which French authorities allege is enabling illicit activities like drug trafficking and child sexual abuse.

Telegram has been blocked in China since 2015. It had once been a safe space to coordinate for human rights lawyers, who used the app's self-destructing "Secret Chat" mode to clear their digital records. During the anti-lockdown White Paper protests in 2022, our researcher Alex Colville, then working for an outlet in China, regularly turned to Telegram to keep tabs on the movement. Its lax rules on group chats let communities form around universities and other institutions. Users shared protest art, kept up with demos elsewhere in the country, or just let off steam. ”Unless speech control within the Great Firewall is relaxed, the direction of the zero-Covid policy won't change," read a comment on one account. But posts like this one reached only a few thousand in Beijing, a city of 23 million. Most groups in the capital were less high-minded, geared to creating a digital red-light district beyond the reach of censors.

It's likely that the White Paper protesters learned how to organize on Telegram from their peers in Hong Kong. I was glued to the app during the 2019-20 anti-government protests. Its mix of encrypted messaging and “supergroups” was perfect for protesters to communicate. Dedicated Telegram channels, with tens of thousands of members, were used to share protest plans. They also tracked police movements, helped detained protesters, and organized rides home. After street protests were quashed, channels were repurposed. They began to give updates on protest-related legal cases and track the spread of Covid-19. This was during the early days of the virus when the local government was following China's lead and downplaying the pandemic.

At one point, there was talk of Hong Kong following China's lead in banning the app as well. In the end, though, authorities found that the app could actually help round up movement leaders. Phone searches on arrested protesters led to the identification and arrest of the moderators behind prominent Telegram channels. Today, the few that remain active are those with moderators based abroad or ones that offer updates like court rulings — with no commentary.

Since then, awareness of Telegram's flaws has grown. It does not offer end-to-end encryption by default, and anyone with access to the company's servers can read users' messages. Most journalists and activists have moved sensitive communications to more secure apps like Signal.

CHAIN REACTIONS

In the Looop

Speak Out HK (港人講地) and its parent organization Looop Media (圈媒體) are far from Hong Kong’s best-known media groups. But the online news outfit does enjoy one superlative: in 2019, in its first and only appearance in an annual survey on media reliability by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, Speak Out HK was ranked as the least-trusted news site in the whole territory. Across all mediums including print, radio, and television, its poor reputation was surpassed only by the state-run newspapers Ta Kung Pao (大公報) and Wen Wei Po (文匯報).

For a news source struggling to find a foothold in a competitive and oversaturated market, this may have been a death knell for their prospects — but Speak Out HK was never strictly founded as a news source to begin with. Soon after it got off the ground in 2013, it was already being described as the “propaganda department” of Leung Chun-ying (梁振英), who served as Chief Executive of Hong Kong from 2012-2017 and was subsequently appointed vice-chairman of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference.

In the years since, the Looop stable has only grown, adding outlets in new mediums, languages, and social media platforms. Their unlikely success tells us as much about the “new era” for media in Hong Kong as does the demise of so many of its erstwhile competitors.

To find out how they did this and what it means for Hong Kong, read my recent investigation into Looop Media, the first in a new Lingua Sinica series.

CMP IN THE HEADLINES

Smart Watches, Dumb Answers

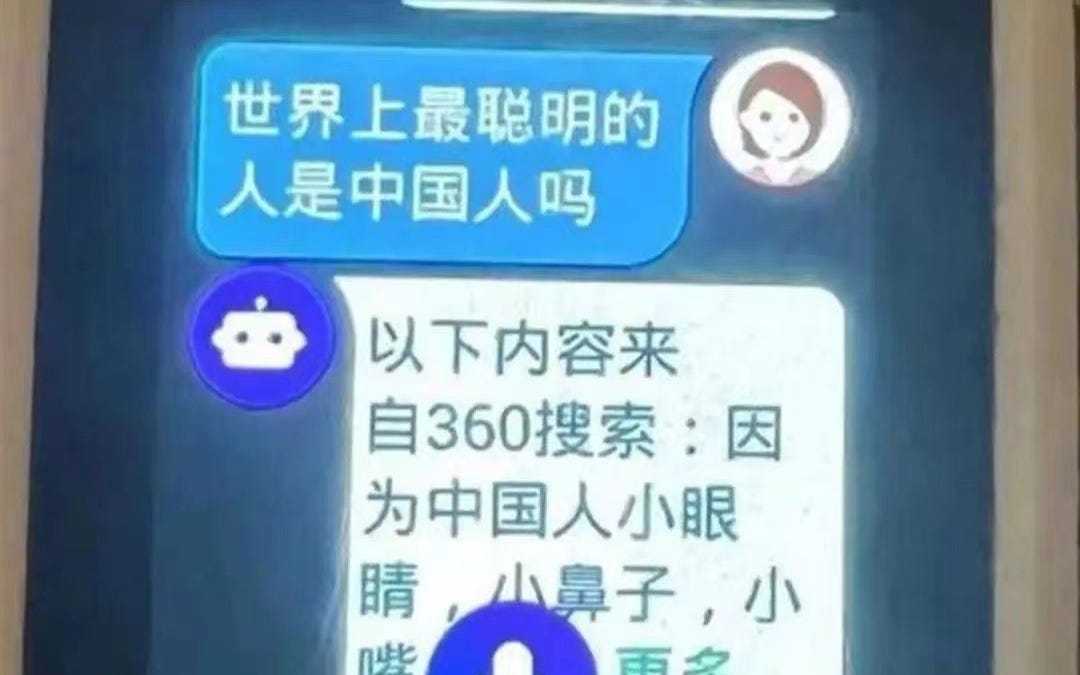

When we think of a machine, we think of something that blindly follows instructions and is totally within our control. But AI's current design is a paradox. It has unreadable, unpredictable, and uncontrollable rules all its own. It’s therefore inevitable that AI will occasionally say the wrong thing. But that’s dangerous in the charged political atmosphere of the PRC.

Security company Qihoo 360 learned this the hard way late last month. One of its smartwatches for children was accused of insulting the Chinese when it gave a terrible answer to the question, "Are Chinese people the smartest in the world?”

The watch replied, "Chinese people have small features and big faces. So, they seem to have the biggest brains of all races. There are indeed smart people in China, but the dumb ones I admit are the dumbest in the world.” The company’s CEO was forced to respond that the product did not use AI, despite the company having marketed it as using just that. Since we broke the story in English, Radii China picked it up. Also, Voice of America interviewed CMP researcher Alex Colville on the issue.

It was not the first time a Large Language Model messed up, and it won’t be the last. Since the Qihoo 360 incident, two more stories have emerged of dumb answers from smartwatches. A Xiaomi watch appeared to deny the Nanjing Massacre, one of the worst atrocities in modern Chinese history. Then a watch from Guangzhou-based Xiaotiancai (小天才) answered a child’s query about Chinese people's honesty. “The Chinese are the most dishonest and hypocritical people in the world,” it said. The child’s parents then smashed the watch with a hammer.

Lingua Sinica also got a shoutout this week from the Big Lychee blog by HK Hemlock, who cited my investigation into Looop Media in his post on the Stand News trial.

Juxtaposing the fates of the two can tell you a lot about what’s happened to Hong Kong media over the past five years: Stand, the city’s most trusted digital news outlet, was shut down in the national security crackdown and its top editors have now been convicted of sedition; Looop’s Speak Out HK, meanwhile, the city’s least-trusted digital news outlet, has found backers at the highest levels of the local and central governments.

CHINA CHATBOT

What is the China Internet Investment Fund (中国互联网投资基金)?

The China Internet Investment Fund (CIIF) is run by the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC), the country’s top internet control and planning body. This makes it the Party’s investment arm for the internet, the fund claiming it wants to put money into building “a strong cyber power.” It has received a lot to play with: 100 billion RMB ($14 billion).

This is nowhere near the budget for developing computer chips. But the money CIIF invests matters less than the influence it can wield with a small stake in a company. One percent gets the fund board representation and sometimes veto powers. It also signals the leadership’s interest in a business’s strategy, potential, prominence, or quality. CIIF has invested in over 100 tech companies. Since the late 2020 crackdown on private tech firms, it has expanded to Alibaba and digital media firms like Kuaishou, ByteDance, and parts of Sina Weibo.

AI has its own part to play in this. In his Third Plenum explanation, Xi Jinping said large firms should be the "backbone" of tech innovation. They are to be the dynamo that drives China forward. Private tech companies have been pushing the boat out with Large Language Models, the foundation of cutting-edge AI. Having a stake in these companies gives the Party an extra inside to the development process.

So it follows that they’ve put money into some big AI providers like SenseTime and small ones like Zhongke Wenge, along with a host of others. Each company on their AI investment list looks promising. Many Chinese and Western firms, as well as national government bureaus, use their products. In Unitree's case, both the US Marine Corps and the PLA use them.

Read this and more about China’s movements in media and AI in Alex Colville’s China Chatbot bulletin from last week, now available for free. Paid Lingua Sinica subscribers will receive an early-bird offering for each edition.

ANTI-SOCIAL

Time to Say Goodbye to Weibo?

In Xi’s “New Era” signs point to the untimely end of the Weibo Era.

In its early stages in 2009, Sina Weibo built its success on larger-than-life personalities known as the “Big Vs” (大V), who were meant to be magnets attracting conversation — and much-desired traffic — to the platform. The strategy worked, and by 2010 media would proclaim that China had entered the “Weibo Era” (微博时代). But within several years, the idea of a privately-owned tech platform building mass audiences outside of CCP control would become untenable for the leadership. A 2014 crackdown on “Big Vs” was the beginning, some might say, of the inexorable unraveling.

Now, 15 years on from the “beta” launch of Weibo, it may be time to ask: has life gone out of the platform? This week, private tech news service 36Kr ran a feature about the lack of any genuine celebrities in attendance at Weibo’s “Super Celebrity Festival” (微博超级红人节) awards. At Weibo’s initial launch in 2009, users were attracted by the chance to hear directly on a range of social, economic,and even political, topics from informed experts who accrued large followings, and were generally known as “public intellectuals” (公共知识分子), or gongzhi for short.

For more on the history of Weibo as a vibrant — if always under pressure — public space, and notes on its slow, inexorable demise, read Alex Colville’s take at CMP.

GOING GLOBAL

Positively Friends

China tries to convince journalists from Indonesia that they are duty-bound to serve as diplomats.

Over the weekend, media representatives from Indonesia gathered with their Chinese counterparts at a forum in Beijing to discuss “friendship” and cooperation — a further sign of China’s concerted media diplomacy push across Southeast Asia to encourage trade and investment, and shape public perceptions of its regional role.

The September 1 event, the second annual China-Indonesia Media Forum (中国-印尼媒体论坛), was attended by scores of mainstream media from both countries, according to a report from the official Xinhua News Agency, as well as think-tanks and state officials.

According to a report from China Daily, an outlet directly under the Information Office of China’s State Council, the meeting focused on “the media’s positive role in building a community with a shared future for China and Indonesia.” This reference to a central Chinese Communist Party (CCP) buzzword in foreign relations, closely associated with General Secretary Xi Jinping, underscored the largely diplomatic nature of the event, which combined talk of bilateral “friendship” with discussions of larger media trends and media technology developments.

Though the forum was framed as a media-to-media event, the think-tank behind it, the Academy of Contemporary China and World Studies (当代中国与世研究院), or ACCWS, is directly under the CCP’s Central Propaganda Department.

Read David Bandurski’s unraveling of the story at CMP.