Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 30 Nov

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

It’s hard to believe that, in my last note, we stood on the precipice of a political earthquake in Taiwan. The country’s opposition parties were about to unite in an unprecedented coalition to unseat the ruling Democratic Progressive Party of President Tsai Ing-wen. What for months had looked like a guaranteed victory for Tsai’s successor, Lai Ching-te, was being turned on its head.

One day later, it all came crashing down in spectacular fashion. The Kuomintang candidate Hou Yu-ih (together with former president Ma Ying-jeou and chairman Eric Chu), the Taiwan People’s Party’s Ko Wen-je, and independent billionaire Terry Gou converged for talks but instead had a dramatic falling out, all in real-time before the nation’s media. The whole ordeal was live-streamed by every major news outlet in a very Taiwanese mix of radical transparency combined with partisan buffoonery. It was, in the words of NCCU political scientist Lev Nachman, “one of the most dramatically silly moments in Taiwan's history since democratization.”

Following the abrupt breakup, the KMT ordered a freeze-out (封殺) on Ko, who has been banned from sharing the stage (or billboard space) with KMT candidates. The order also applies, according to some reports, to traditionally blue (KMT-supporting) media outlets. The remaining weeks before Taiwan goes to the polls will be a test of the impartiality and professionalism of the country’s mainstream media outlets, which are infamous for their political party allegiances — an issue explored by Xin-yun Wu in our first Substack-exclusive piece.

In the meantime, nothing can be taken for granted in what is undoubtedly the most exciting, unpredictable, and sometimes messy election in the Chinese-speaking world (Hong Kong’s upcoming District Council vote is another matter — read “Spotlight” below to see how that’s shaping up).

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

Dominating the front page of the Wednesday edition this week of the CCP’s official People’s Daily newspaper was a huge report on the pressing need for China to build a “foreign-related legal system” (涉外法制). Given heightened concerns in recent years over China’s long-arm tactics globally — including election interference and transnational repression — such high-level talk at a collective study session of the CCP Politburo might immediately raise eyebrows. What exactly does China mean by “strengthening foreign-related rule of law” (加强涉外法治)?

THE BOTTOM LINE: China is working to develop a body of law to deal with the outside world and what it perceives as unfair activity by foreign governments as well as foreign organizations that might impact the country’s overseas interests.

Part of China’s planned response, which was outlined in greater detail at the 4th Plenum of the 18th CCP Central Committee in October 2014, involves greater involvement in international law-making (which, mind you, was already happening before Xi’s rise to power in late 2012). China plans for more of its legislation to have an extra-territorial effect [Background HERE], and also hopes more China-related dispute resolution can be heard inside China.

Given the CCP‘s extreme sensitivity to issues of perception, it’s not surprising that these considerations also have a strong media and communication component. In a strongly-worded article posted to its WeChat official account on the day of the Politburo study session, the Ministry of State Security (国家安全部) laid out a series of looming risks to China’s interests internationally, saying that “individual countries are blocking, containing and suppressing [us] globally.” The article noted not just threats to individuals, enterprises, supply chains, infrastructure, and so on — but also to China’s image and reputation. “Some countries, as well as organizations and individuals with ulterior motives, have discredited [China’s] international image and spread false information, hindering the progress of overseas projects,” it said.

For related reading, we recommend Matthew Erie’s “Foreign Policy Implications for China’s “Foreign-Related ‘Rule of Law,’” as well as SPC Monitor's excellent overview of the Supreme People's Court's specialized report on foreign-related adjudication work.

IN THE NEWS

The Golden Horse Awards, a film event honoring works from the world of Chinese-language cinema that has been called “the Chinese Oscars,” kicked off on November 25 at Taipei’s Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hall. Much coverage in Taiwan and elsewhere in the region, such as this report from Taiwan’s semi-official Central News Agency, focused on the fact that this year’s awards marked the first time in five years that film stars from China have attended.

Unhappy China

For many years, the red carpet at the Golden Horse Awards was the place to look for all of the major stars of Chinese-language cinema — from Taiwan, Hong Kong, China, Malaysia, Singapore, and beyond. That changed in 2018, after Taiwanese director Fu Yue (傅榆), the daughter of Malaysian and Indonesian Chinese parents, said during her acceptance speech for the best documentary award: “My greatest hope as a Taiwanese person is that one day our country will be treated as truly independent.”

The statement prompted immediate ire from China, where the official Global Times newspaper, a spin-off of the CCP’s People’s Daily that generally deals with international affairs, said that Fu’s words were “wrong and damaging to the influence of the Golden Horse Awards, which in turn will also damage Taiwan's influence in the Greater China region.” Months later, on August 7, 2019, a decision by the China Film Administration (中國國家電影局) to prevent films and artists from the PRC from participating in the annual awards was reported by China Film News (中国电影报), an official CFA publication. The decision sparked a debate in Taiwan and elsewhere in the Chinese-speaking world about what, as Taiwan’s The Reporter wrote, “would be the long and short-term effects of a Golden Horse Awards without China?"

Politics Slips In

Even without a formal dropping of the 2019 ban from the CFA, Chinese films and stars were back at the 2023 Golden Horse Awards. That does not mean, however, that "political interference" (政治干扰) — to borrow one of the more provocative terms favored by the Global Times over the Fu Yue case — is out of the picture. This year’s top prize winner in the documentary category, The Memo (備忘錄), is a video diary made under lockdown in China during the pandemic, depicting the experience of a couple living in a small apartment in Shanghai — as the authorities bumble through the crisis. Needless to say, all discussion of the documentary inside China is being censored.

NEWSPEAK

For years, the regular ‘Clear and Bright” (清朗) online cleanup campaigns of China’s top internet control body have been a constant reminder to platforms and citizens to keep their behavior in check. But in recent months these campaigns have come with such dizzying frequency that keeping track of them has become a daunting task.

The latest case in point is an expansive list of regulatory priorities released earlier this month that includes not just concerns such as doxxing and cyberbullying — shared by regulators and citizens around the world — but also vague value labels that have the authorities at the Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) meddling directly into areas such as “regional prejudice,” “gender antagonism,” and “class antagonism.”

What do these terms mean? And how did a Communist Party that lived and breathed class struggle for decades get to this point? Find out in our latest piece: “No Class War Please, We’re Communists.”

SPOTLIGHT

The Political Price of Hong Kong’s “Care Teams”

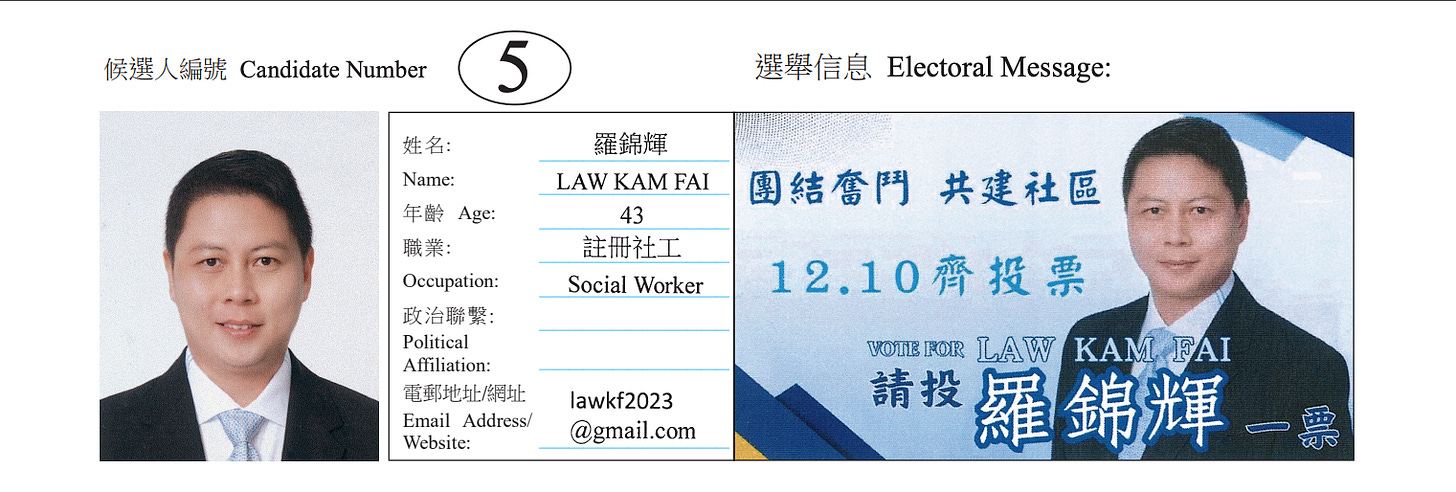

The local district council candidacy of Law Kam Fai, who only last year was employed by China’s central government office in Hong Kong, offers a glimpse of how Beijing is working to insinuate itself directly into Hong Kong politics.

In an exclusive report this week, Photon Media — an outfit of exiled Hong Kong journalists in Taiwan — exposes Law’s deep and possibly ongoing ties to the central government, as well big local businesses that have donated millions to a fund he chairs. None of these facts — which should disqualify candidates based on Hong Kong law — have been disclosed to the public. The government’s response instead seems to imply that his loyalty is all that matters.

Law’s case also offers a fascinating glimpse into the world of “Care Teams” (關愛隊) in Hong Kong. These are units overseen by the Home Affairs Department that liaise with different organizations in the district to engage in “community-building.” Introduced by Chief Executive John Lee in 2021, they are based on sub-divisions of the city’s 18 districts.

For readers who have been keeping up with our work on Grid-Based Management and the Fengqiao Experience, bells ought to be ringing. The “Care Team” system seamlessly dovetails with efforts on the mainland to enforce new and intrusive forms of social management, mobilizing the masses at the grassroots of society to enforce proper conduct — political or otherwise.

Look out for a full translation of the piece tomorrow on Lingua Sinica.

CMP SHOWCASE

Mere hours after former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger passed away on Thursday morning, the accolades were already pouring in from PRC officials and state media. Without exception, the architect of Sino-US rapprochement was remembered fondly as an “old friend of the Chinese people” (中国人民的老朋友). But what does it mean to earn this monicker? Let’s take a look back at our CMP Dictionary entry for it from earlier this year…

How many “old friends” does China have after six decades? From 1949 to 2010, 601 individuals from 123 countries earned the moniker in the People’s Daily. Before the late 1970s, they were an exclusive crowd. But after the end of the Cultural Revolution and the beginning of China’s reform and opening up, their ranks suddenly swelled. As the country sought diplomatic recognition and foreign investment, friends were all around.

Numbers dipped over China’s brief spell of isolation following the 1989 Tiananmen massacre, but soon picked up again. In the run-up to Beijing’s ascension to the World Trade Organization in 2001, the phrase “old friends of the Chinese people” reached fever pitch.

Like the worst kind of friend, the party-state most reliably checks in on its lao pengyou when it wants something from them. Consider, too, the home countries of China’s “old friends,” which correspond with the country’s diplomatic wishes and concerns. With over 100 “old friends,” China’s historical enemy Japan is home to more than anywhere else in the world — by a long shot. Coming in second, with half that amount, is Beijing’s more recent great-power rival, the United States of America.

Why are there more “old friends” where friendship most eludes China? Because these places are precisely where friends are most useful. They can be summoned for meetings to undermine their own government’s current foreign policy tack, for example — think Kissinger back in July 2023, some might say.

In the use-or-no-use world of the CCP’s “old friends” mentality, there are two paths for the foreigner who speaks out: either be useful to the Party and become an “old friend of the Chinese people,” or oppose it and become a “foreign force” (境外势力).

Read the full piece here.

ON A LIGHTER NOTE

Lithe Metaphors in the Taiwan Elections

In a post to his Facebook page on November 21, 2023, presidential candidate and current Taiwanese vice president Lai Ching-Te (賴清德) formally announced his official campaign slogan for the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP): “Choose the right people, walk the right path” (選對的人, 走對的路). In the post, this slogan was superimposed over the image of a stern cartoon dog alongside a cat wearing a kind smile.

While the dog image was in fact a tribute to Lai’s recently deceased dog Luke, a Formosan mountain dog, the image was interpreted by some as a subtle dig against China, which in recent years has been known for its ham-fisted foreign policy approach, known as “wolf warrior diplomacy” (战狼外交). The reading was perhaps understandable given Lai’s public contrasting this month of the “wolf warrior” as a symbol of totalitarianism, and the “cat warrior” as a symbol of democracy.

But where does the cat come in?

Enter the Cat Warrior

It’s no secret that Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), the current president of Taiwan for the DPP, has two pet cats and is an avowed cat lover, something many outlets, including Mirror News, have noted over the past week. But cats have leaped into political coverage this month especially because of Lai Ching-te’s announcement on November 20 (Storm Media), that he had appointed as his vice presidential running mate Taiwan’s former representative to the US, Hsiao Bi-Khim (蕭美琴).

Hsiao, who as FTV News and other outlets have noted, is a hardcore cat lover, has even referred to herself since 2020 as a “Cat Warrior” (戰貓) — a clear broadside that China surely has not found cute, and which even brought attention in international media. In recent months, the notion of “cat warrior diplomacy” has suggested a Taiwanese way of dealing with diplomacy. Like a feline, Taiwan has had to maintain its balance flexibly and elastically in the face of a difficult international situation. And cats, of course, are famously aloof — and another word for that might be “independent.”

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Open Societies VS Sharp Power

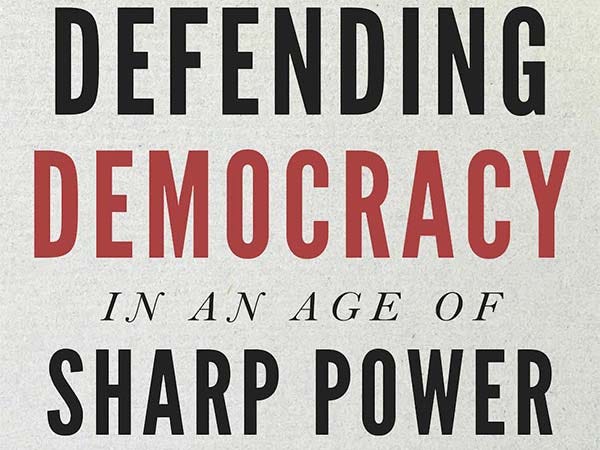

In the recently published Defending Democracy in an Age of Sharp Power, editor Christopher Walker and contributors explore how authoritarian states like China are deploying “sharp power” to undermine democracies from within by weaponizing universities, institutions, media, technology, and entertainment industries. We asked Walker, who is Vice President of Studies and Analysis at the National Endowment for Democracy, a few questions about the book’s findings.

Lingua Sinica: In his meeting with Joe Biden in San Francisco earlier this month, Xi Jinping renewed the now-familiar reassurance that China does not export its ideology. After reviewing all the case studies explored in this book, what do you think about the veracity of this statement?

Christopher Walker: There is no question that the Chinese Communist Party is competing with determination in the ideas sphere, at home and abroad. It leverages now formidable global channels of information influence to deliver its messages and narratives at a global scale. As Nadege Rolland explains in her contribution to the book, since assuming the country’s paramount leadership position Xi Jinping has given increasing prominence to “discourse power,” through which words are used to “create a narrative, and to manipulate the perceptions, behavior, and decisions of others”. Given the fact that Beijing is touting ideas such as the virtues of one-party rule, it’s wishful thinking to imagine that the CCP is not promoting its ideas, with purpose, to the wider world. And wishful thinking is not a strategy, of course. Open societies need to be far more clear-eyed about the ambitions and intentions of the Chinese Party-state and, accordingly, develop more systematic approaches for responding to the public arguments and ideas the CCP uses to advance its interests. [Editor’s Note: See our entry in the CMP Dictionary for more on “discourse power”].

LS: Defending Democracy in an Age of Sharp Power looks at how the democratic world is losing the "battle of ideas" because of how authoritarian regimes exploit asymmetries to skew conditions in their favor. How do we even the playing field, particularly in the media sector?

CW: One of the patterns that emerges from the book is that the Chinese Party-state has progressively built out an extensive global media and information infrastructure, one that has been underestimated by many observers. Sarah Cook’s chapter spells out how the CCP “has dramatically expanded its efforts to shape media content in every region of the world” and the key ways in which Beijing seeks to manipulate the global information environment: “through propaganda; spreading disinformation; censoring critical coverage; and acquiring or building the infrastructure used to disseminate news and share information”. Given the extent of the investment over a protracted period of time by the Chinese Party-state, there is no quick or simple way to level the playing field in the media sector. Fundamentally, open societies need to continue to improve their ability to understand how the CCP is operating in the modern information space, while also devising new ways to compete and more affirmatively privilege open and pluralistic media, rather than what’s on offer from the CCP that privileges censorship, manipulation, and propaganda.

LS: Apart from institutional changes, some of the authors also pointed out the need to improve citizens' "immune systems" when it comes to resisting the authoritarian offensive. What are some key suggestions you would make to readers to improve their immune systems?

CW: I think it is important to recognize the need for a different quality of preparation within open societies to deal with the ongoing, persistent authoritarian offensive. The decision-makers in Beijing, but also in Moscow and Tehran, see the payoff to be achieved through asymmetrical arrangements that enable them to penetrate and exploit open systems. Until autocrats believe the costs of such activity are sufficiently high to outweigh the benefits, they will continue to probe and attack. Given the extent of the ambition of the authorities in China — but also Russia and Iran — a stronger understanding of their influence efforts needs to be mainstreamed, for instance, into civil society efforts relating to freedom of expression, press freedom, and internet freedom. Concerning China, any sustainable effort to strengthen the immune system of open societies must be grounded in a deepening understanding of the Chinese political system and its foreign policy strategies, which too often tend to be extremely limited. In far too many cases, there are few journalists, editors, and policy experts who have a deep understanding of China and can share their knowledge with the rest of their societies. Martin Hala [of Sinopsis] makes the fundamental point that “democratic societies’ resilience…lies in their ability to wield their own ‘magic weapon’ – their openness” which allows them “to freely research, analyze and publicize CCP sharp-power manipulations” in order to frustrate the authoritarians’ corrosive objectives.

Related CMP Case Studies:

“Reading China’s Media Counter-Attack”

October 5, 2023

As China responded with fury to a report alleging it has invested billions to build a "global information ecosystem," our analysis of that counter-attack, which relied in large part on cloaked propaganda accounts, substantiated the report's main thesis.

March 1, 2022

Aired on the Discovery Channel across Southeast Asia and India, Journey of Warriors may look like just another documentary survival series. But it is co-produced by a production group directly tied to the CCP's Central Propaganda Department.

“Inside China’s Global Media Blitz”

March 17, 2021

A full-page spread in the People's Daily boasts of making "media drops" of 750 unique articles in 12 languages and nearly 200 media outlets in 40+ countries all in just one week — offering a rare glimpse into the CCP's efforts to sway global public opinion.

STORYTELLERS

A Brief Flare of Defiance

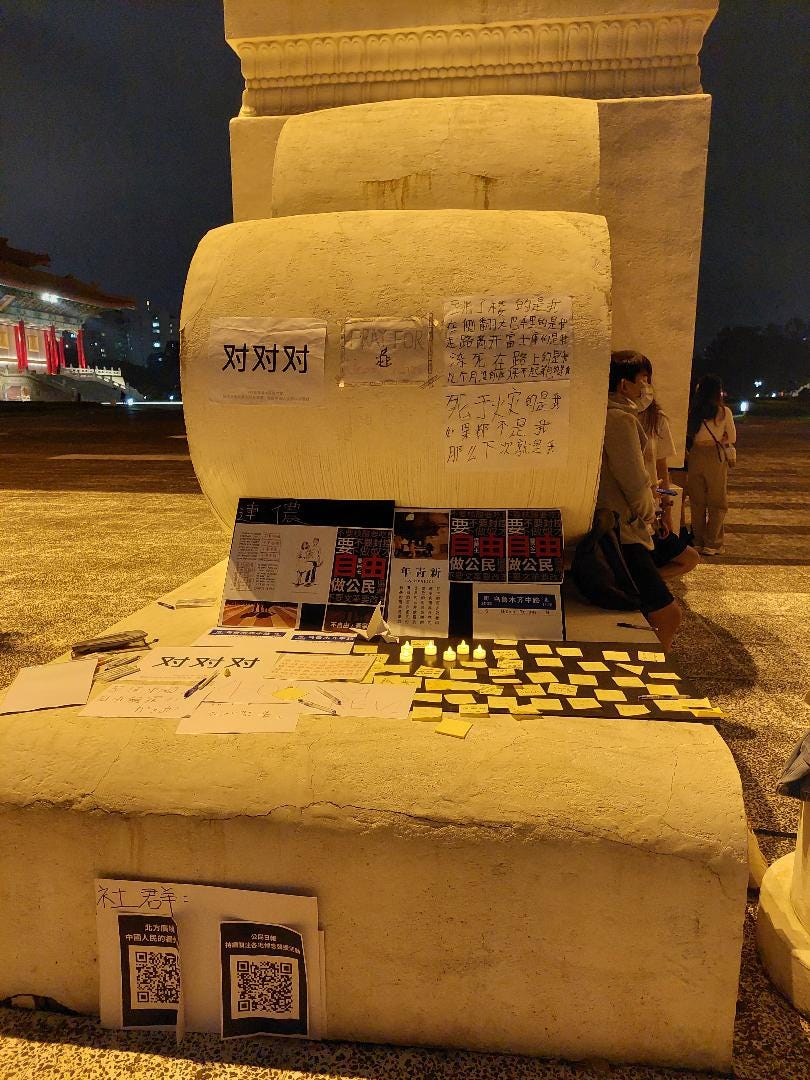

Last Friday, November 24, marked the one-year anniversary of the deadly apartment fire in the city of Urumqi in northwest China, a tragedy that sparked protests across the country against stringent Covid-19 lockdown policies and the leadership’s unrelenting censorship and cover-up of the extreme pain these policies caused — symbolized simply and dramatically by blank sheets of white A4 paper.

The one-year anniversary of the White Paper Movement (白纸运动) has been marked by Chinese this week in cities across the world as they reflect on what the AP described on Tuesday as “the brief flare of defiance.”

To commemorate the anniversary, we are re-sharing our translation of a wonderful reflection published on December 4 last year by Initium Media. More than a simple fist-pump of solidarity, the essay is an exploration of the revealing and significant fault lines within the movement over Han identity and the crucial question of rights, dignity and freedom for the Uyghur population. Read “Confessions of a Han Chinese Woman” HERE.

The writer finishes the reflection by urging others to familiarize themselves with the plight of China’s Uyghurs by listening to their voices and writing. On a related note, we recommend Waiting to Be Arrested at Night: A Uyghur Poet’s Memoir of China’s Genocide, by Tahir Hamut Izgil. Released on August 1 in English, the book is a gripping tale of one family’s escape from China’s campaign of repression against its Muslim minorities. A well-known modernist Uyghur poet, filmmaker, and activist, Tahir Hamut Izgil is currently living in exile in the United States.

The Reporter, one of Taiwan’s leading professional news outlets, has published a strong review of the book this week, following its release earlier this month in Taiwan with an online dialogue between Tahir Hamut Izgil and pro-democracy activist Lee Ming-che (李明哲).

GOING GLOBAL

Last week, China kicked off the second edition of the Global Digital Trade Expo, an event hosted by the provincial government in Zhejiang, which is home to the headquarters of internet giant Alibaba as well as hundreds of digital startups. Promoting digital trade in a letter addressing the expo, Xi Jinping stressed China’s concept of the “Digital Silk Road” (数字丝绸之路), which state media in related reporting called “the technological dimension of the Belt and Road Initiative.”

In the latest entry in our CMP Dictionary, researcher Dalia Parete explores the “Digital Silk Road” as an initiative to fund, develop, implement, and expand China’s technological capabilities abroad, thereby promoting greater PRC sway in the standardization of global digital infrastructure. Learn more.

DID YOU KNOW?

The Elegy and the Ode

The front page of the People’s Daily this Monday featured a hymn of sorts to the Yellow River. “Xi Jinping’s Yellow River Sentiment” waxed lyrical about the “mother river” of the Chinese nation and the responsibility “inherited by the Communist Party” to govern its flow. “Only under the leadership of the CCP can we truly realize the historic transformation of the Yellow River,” the General Secretary mused as he “deeply pondered the millennia-long relationship between governing the river and governing the nation.”

Fans of Karl A. Wittfogel’s theory of “hydraulic despotism” will find a lot to read into here. But for our part, it reminds us of another song of the Yellow River — one that strongly influenced Chinese media in the reform era but was subsequently banished from the airwaves.

An Elegy to Bygone Openness

The fact that 1988’s River Elegy (河殤) was broadcast at all by state-run China Central Television (CCTV) is a testament to how times have changed. The six-part documentary series hinged on the contrast between the backwards, inward-looking “Yellow River culture” of China’s past and a more open and forward-looking “blue ocean culture” embodied by the West. To progress, it posited, China had to sail past its silty inland waters and join the family of nations on the open sea.

Unsurprisingly, the series is filled with self-flagellating attacks on Chinese culture and dewey-eyed fawning about the West. But, if you read between the lines, there’s far more to it than that — a reflection of the strong pro-reform impulses that were in the air in the late 1980s.

Speaking from exile in the United States, River Elegy’s director Su Xiaokang (蘇曉康) later explained, "We did not dare to confront the CCP system, and therefore we attacked our ancestors instead." The primary target, in other words, was not traditional Chinese culture at all but the prevailing political system under which they lived.

The documentary series' apparent admiration for all things Western, too, is more about China than the West itself. River Elegy took the CCP’s anti-Western rhetoric and flipped it on its head, creating a counter-discourse of anti-establishment Occidentalism that used a politically correct form of reductionist thinking to critique the CCP’s own oppressive ideology.

The days of “River Elegy fever” (河殤熱) — when the series was debated nationwide in the lead-up to the Tiananmen Square protests — are firmly in the past. But as “Xi Jinping’s Yellow River Sentiment” shows, the silty, unforgiving waters of the Yellow River are as evocative a political symbol as ever.