Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 30 May

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

Many a Taipei-based journalist was looking forward to a lull after the inauguration of Taiwan’s new president Lai Ching-te on May 20 — a well-deserved respite after weeks of reporting on the power transition and networking with colleagues visiting from out of town.

Instead, we got the biggest protests the capital has seen since the 2014 Sunflower Movement. In tandem with “punitive” PRC military drills surrounding the country, it’s been a rocky and all-too-eventful start to Lai’s tenure. And with the opposition-dominated legislature granting itself new prosecutorial powers that could hamstring his administration, it looks like a rough four years ahead that will demand strong and informative journalism all around. For more on both Lai’s inauguration and the “Bluebird” protests, see “In the News” below.

Before we get to that, though, we need to talk about some exciting changes coming to Lingua Sinica. Next month, we’re introducing a subscribers-only tier for readers who want to support what we do here at the China Media Project and benefit in the process. If you’ve been enjoying our newsletter, interviews, and articles, don’t worry — none of our regular content will be hidden behind a paywall.

But if you want to dig that bit deeper, we’ll be offering even more. This will include in-depth monthly discourse reports that break down and analyze the most important trends and terms in CCP discourse (which you might have known previously from Bill Bishop’s excellent Sinocism), and behind-the-scenes looks at how we read Chinese media, so you can use the same tools and methods as us to make sense of the evolving Chinese-language media landscapes of the mainland PRC, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and diasporic communities.

Subscriptions will start at US$5 a month for our “Low-Level Red” (低級紅) plan. This will get you the subscribers-only content outlined above. For pledges of US$120 a year and above, you can upgrade to the “High-Level Black” (高級黑) tier, which gives you all that plus access to archived material as well as instant access to future subscribers-only offerings — along with the satisfaction of knowing that you are supporting our long-term development. For more on what these terms denote in PRC state media discourse, see “Flashpoints” below.

In the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing more information about these subscription plans, both here on Substack and on our socials. Hopefully, we’ll see some of you among the ranks of our dijihongs and gaojiheis soon — and if not, please keep reading just as before!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

IN THE NEWS

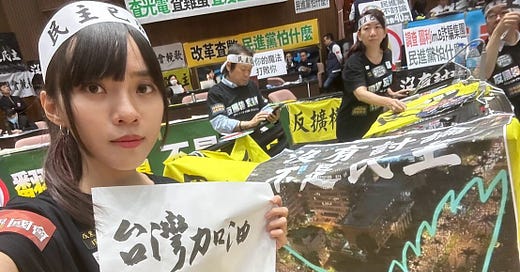

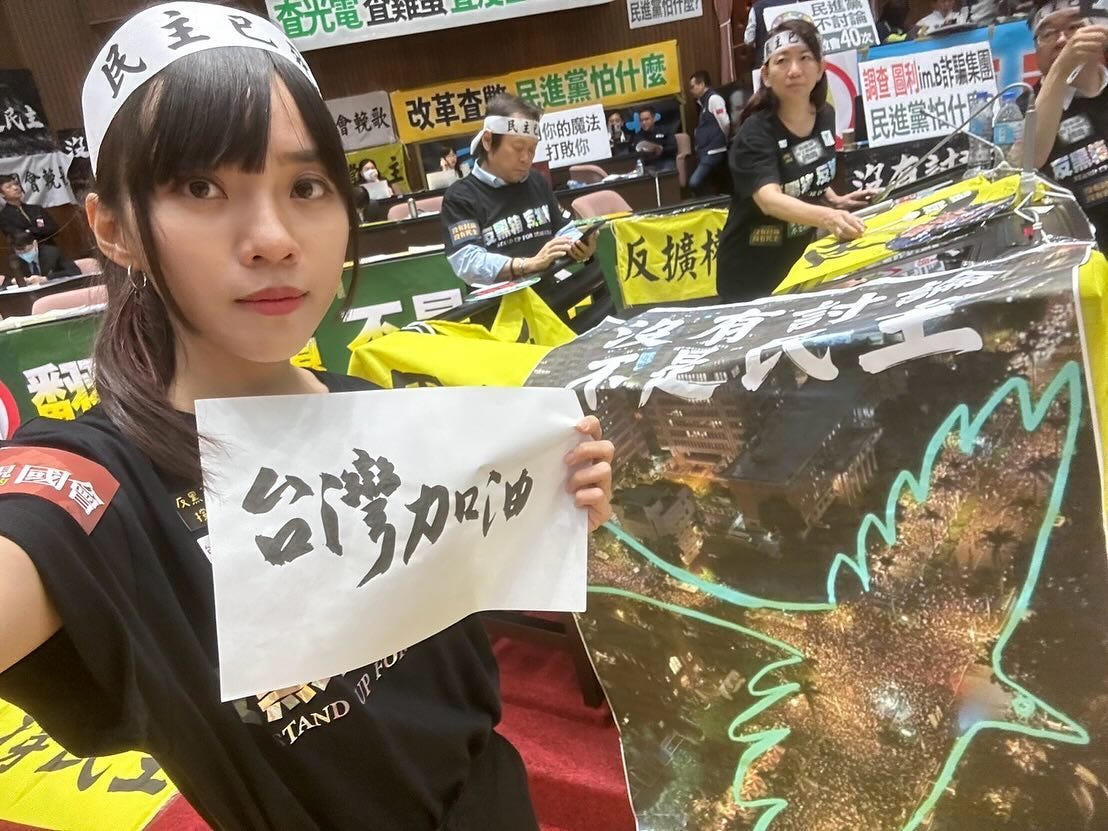

Your Bluebird Movement Glossary

Since May 17, Taiwan has witnessed the emergence of a new grassroots social movement stemming from opposition to the contentious expansion of legislative powers pushed through by the Kuomintang (KMT) and Taiwan People's Party (TPP) — which many have seen as a power grab. As the student-led Bluebird Movement continues outside the Legislative Yuan, related slang has taken wing on social media platforms, including Threads and X.

Here is our rundown:

Bluebird Movement (青鳥運動) — According to Brian Hioe, the founding editor of Taiwan’s New Bloom online magazine, the designation “Bluebird Movement” is a play between the similar sounding “bluebird,” or qingniao, and the place name Qingdao (青島), a reference to Taipei’s Qingdao East Road (青島東路), where the protests have mainly unfolded.

Turnabout Grasses (回頭草) — Emerging more recently in the protests, this term applies to those who voted for the TPP in the January elections — handing the opposition party crucial third-force status, which is now bolstering the KMT’s razor-thin majority — and now find themselves regretting their votes and joining the protests. The term comprises two words, the verb “to turn back” (also meaning to regret one’s actions), and the word for “grass,” a reference to TPP supporters, as the party said during the campaign that its base were ordinary citizens coming from the grassroots of society. As one user on Threads summed up the meaning of this new moniker: "What does the TPP mean by 'handing the nation back to the people'? I'd rather request that they give me back my vote."

Onion Fans (蔥粉) — This term has become a familiar new derogatory label during the protests to refer to supporters of Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌), a legislator from the TPP who was elected to the Legislative Yuan back in January. A leading figure during the 2014 Sunflower Movement, the student protests that arose in opposition to a proposed cross-strait trade agreement, Huang has been panned for what some see as an unconscionable shift in his political stance. Why onions? This derives from a widely-circulated video of Huang in which he holds a stuffed velvety green onion. Huang’s “onion fans” are viewed with unhappiness by many who are angered by the recent actions in the legislature and support the protest movement.

FOREIGN FORCES

Taiwan Unhinged

Taiwan Untangled is a new documentary from CGTN, the international arm of China’s state broadcaster CCTV, that aims to make the case for China’s claims over the island democracy and to portray its democratically elected leaders as dangerous firebrands provoking Beijing.

Its title in Chinese, directly translated, might more fittingly be: “Taiwan in the Eyes of One Western Person” (一個西方人眼中的台灣). The titular Westerner is the Right Honorable George Galloway, a British Member of Parliament who hasn’t missed a beat when it comes to the official CCP line. Last year, he gleefully told a forum hosted by China's government that "the Chinese system is the one moving forward." He recites how Taiwan has been a part of China since time immemorial (it has not), how the US is the real aggressor by standing with Taiwan, and how recently elected President Lai Ching-te is a traitor in America’s pocket.

"The only real question is how and when Taiwan shall reunite with the mainland,” says Galloway in a thinly veiled threat. “Shall Taiwan wait for the apple to fall from the tree, or will it wait for the tree to be shaken?" Galloway dutifully stays on script. However, his odd rendering of Chiang Kai-shek as “Kang” Kai-shek is a stand-out reminder that even if these are personal convictions rather than borrowed ones, the MP has little standing to speak about Taiwanese history.

The Callow Way

Joining Galloway on screen is Calla Walsh, a young American “peace activist” who indiscriminately supports America’s enemies abroad, including terror group Hamas, Iran’s brutally repressive theocracy, and, naturally, the Chinese Communist Party. “To portray China as the aggressor is absolutely bizarre,” Walsh says, “when I think China has the right to defend its territory against this imperial aggression.”

These perplexing views are pretty damning hypocrisy. Galloway has been a supporter of Palestinian independence since at least the late 2000s, and Walsh has been prepared to literally set fire to Israeli companies to protest the war in Gaza. But here both are amplifying propaganda for the annexation of a contested state by a powerful and militaristic neighbor who claims it as its own.

Beyond China’s typical cherry-picking of foreign voices to speak its agendas, the CGTN propaganda piece could be seen as a testament to how the ongoing horrors in Gaza — and Washington’s failure to hold its ally to account — are driving some headlong into the pro-Beijing camp. The CCP evidently has no qualms about taking advantage of just how little they know about both Taiwan and China.

FLASHPOINTS

Low-Level Red, or High-Level Black?

In a Hong Kong newspaper, a picture of a modern dystopia from last week:

A recently passed national security law has sent a ripple of fear through society. Unaware of when they might run afoul of this harsh yet vaguely worded edict, the populace has been cowed into silence, left to wonder who will be the next victim of this encroaching white terror. With authorities encouraging citizens to report on any perceived threat, it feels like no one can be trusted and no one is safe.

If you thought that sounded like Hong Kong today, under the national security law imposed by Beijing and the recently legislated Safeguarding National Security Ordinance, you’re dead right. But this is how the Ta Kung Pao (大公報), a Communist Party-affiliated newspaper in Hong Kong, is now describing the atmosphere in the United Kingdom following the death of a British man accused of spying for Hong Kong.

Former Royal Marine Matthew Trickett, 37, was one of three people arrested under the 2023 National Security Act for allegedly carrying out aggressive surveillance on activists in exile at the behest of the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in London. Shortly after being released on bail, he was found dead in a local park.

The Ta Kung Pao’s pen-portrait op-ed is so untethered to reality in the UK, and yet so vividly reminiscent of Hong Kong — which today convicted 14 pro-democracy figures of “subverting state power” over an unofficial primary they held ahead of local elections — that it invites the question: is this an example of the type of content referred to in China as “low-level red”(低級紅) or “high-level black” (高級黑)?

These phrases refer to two kinds of propaganda or official prose that PRC authorities are keen to avoid. “Low-level red” is pro-Party content so cravenly, cringingly sycophantic that it ends up, unintentionally, making a mockery of whatever, or whomever, it sought to elevate. The textbook example of this is when volunteers at the 2018 Suzhou Marathon attempted to force a national flag upon a Chinese runner leading the pack, causing the would-be champion to fall behind and finish second.

“High-level black” behavior, on the other hand, is more insidious. Not unlike the proverbial “smile that hides a dagger” (笑里藏刀), it offers exaggerated praise to satirize. “On the surface, it sounds like they are praising you, but in reality, they are harming you,” reads an official guide on how to identify “high-level blacking” published in 2019. “They are actually doing you a disservice by expressing their loyalty and singing praises with too much enthusiasm."

With its hyperbolic language concerning the Trickett case, is the Ta Kung Pao serving up subtle criticism of things at home? Or is it just mortifying the bosses in Hong Kong and Beijing with a cringeworthy act of propaganda?

REDLINES

A Speech Likely to Anger Beijing

As PLA warships and planes buzzed around Taiwan on May 24, the People's Daily dedicated a full-page spread to condemning the new Taiwanese president Lai Ching-te, and the inaugural speech he made four days earlier. Debate has been surging among Taiwan watchers about just how radical or “provocative” this speech really was, and the People’s Daily helpfully lays out the parts of it Beijing found the most offensive.

The three "separatist fallacies" the paper accuses Lai of "wantonly proclaiming" are the phrases “sovereign and independent” (主權獨立); "neither side [of the Taiwan Strait] is subordinate to the other" (兩岸互不隸屬); and "self-determination of Taiwan residents" (台灣住民自決).

Only one of these — "sovereign and independent" — actually appeared verbatim in Lai's speech, in which he said “[the] Republic of China Taiwan is a sovereign, independent nation." (中華民國臺灣是一個主權獨立的國家). The remaining phrases are all paraphrased or represent Beijing's interpretations. For example, Lai in fact said "[the] ROC and the PRC are not subordinate to each other" (中華民國與中華人民共和國互不隸屬). The detestable "fallacy" of self-determination presumably refers to when Lai said in his speech that “sovereignty lies in the hands of the people" (主權在民).

It's worth noting that the "neither side” phrase is nothing new, and neither violates the "One China Principle" nor supports de jure Taiwan independence. The phrase has been used since the 1990s when the ROC finally recognized the PRC government and agreed to talks that led to the "1992 Consensus” now beloved of Beijing (for more on this, see “Source Code”). Both Lai’s immediate predecessor Tsai Ing-wen and her predecessor, pro-China stalwart Ma Ying-jeou, have previously referred to Taiwan as a “sovereign and independent” state.

Another article on the People’s Daily page calls the drills that encircled Taiwan a "firm reprimand for the Taiwan regional leader's provocative speech on May 20," implying that they were organized in a fit of pique within just a few days. Combined with the fact that the most objectionable parts of the speech cited by state media were not particularly new, it seems like they had their minds made up long ago to punish Taiwan for voting in Lai.

SOURCE CODE

The Taiwanese on China’s Side

In the same People’s Daily spread cited in “Redlines” just above, a different article interviewed seven Taiwanese living in China. It presented them as ordinary people “disappointed, worried, concerned, and anxious” about Lai’s China stance, giving the impression that Lai and the DPP are governing without a popular mandate.

But who exactly are these voices?

“People [in Taiwan] can't feel the sincerity of Lai's willingness to communicate with the mainland and are worried about the future of cross-strait relations,” says one Lin Yuanda, whom the piece paraphrases as saying Lai’s remarks were “absurd and dangerous.”

The article presents Lin as an average citizen, “a Taiwanese who has worked on the mainland for ten years.” It neglects to mention that Lin is also President of the Soochow University Mainland Alumni Association — a role that Lin described in 2022 as “assisting communication and exchanges between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait.” Pulling Taiwan and China closer together is very much his bread and butter.

In fact, Lin is one of five quoted in the piece who head similar institutions dedicated to bolstering cross-strait relations. But the author discloses the position of just one. Five of the seven are also taishang (台商) businessmen who have made their fortunes in China, giving them very particular perspectives on the importance of close social and trade relations. Providing economic opportunities is one of the key strategies listed in China’s “overall strategy” for winning over Taiwanese — and for some these opportunities can supersede real concerns about political rights.

The odd one out in the People’s Daily piece is Gao Weihong, a historian at Fujian Normal University, a short drive from the China-side pier where ferries putter out to Taiwan’s Matsu Islands. Gao has also attended seminars at Fudan University to present papers on Communist theory, and has argued that Taiwan independence is invalidated by Marxist axioms that supposedly oppressed nations must be liberated. In his eyes, Taiwan — which chooses its own government and enjoys robust human rights protections and freedoms unimaginable in China — “has not yet escaped the control of imperialism.”

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Malaysia’s Media Landscape

In February this year, the Malaysian government released a revised version of the country’s Journalism Code of Ethics — its involvement raising questions about the Code’s impact on media freedoms.

This week, Lingua Sinica sat down with Professor Benjamin YH Loh, a senior lecturer in the School of Media and Communication at Taylor's University in Malaysia, to explore the implications of these changes. Below is an excerpt of our discussion, slightly edited for clarity. You will be able to read the full interview next week in a special edition of Lingua Sinica, along with a broader discussion of issues in the Malaysian media landscape that includes the impact of China.

Lingua Sinica: What is this updated Code of Ethics, and is it strange that the government is involved?

Benjamin Loh: The updated Journalism Code of Ethics is a departure from the norm where such codes are typically developed by journalists themselves. While the Code does not hold legal weight in Malaysia, it serves as the criteria for issuing government media passes, which are vital credentials for journalists seeking access to government events and parliament.

LS: Why update the Code now?

BL: Originally established in the 1980s, the Code of Ethics was outdated, vague, and open to interpretation. The recent update aims to address contemporary challenges faced by the media industry. Notably, the revised Code emphasizes the importance of naming sources, refraining from accepting gifts, and being mindful of conflicts of interest.

LS: How is it likely to impact the Malaysian media sphere?

BL: A notable concern with the updated Code is its potential use to restrict media outlets critical of the government. This highlights a key issue surrounding the Code's implementation. The rapid evolution of media in the digital age, particularly the challenges posed by social media, is not adequately addressed as the pressure to report news quickly in response to social media trends can compromise the quality and accuracy of journalism. The provision intended to address this specific issue is notably absent from the new Code, which raises questions about its effectiveness.

TRACKING CONTROL

The Lost Decade

In a fitting illustration last week of the Chinese leadership’s unrelenting efforts to manipulate collective memory, an online essay with a shocking revelation about the wholesale disappearance of Chinese internet content spanning the 2000s was deleted by content monitors. But the post, quickly archived and shared, reverberated in platforms beyond PRC-managed cyberspace.

Written by He Jiayan (何加盐), an internet influencer active since 2018, the essay concluded, based on a wide range of searches of various entertainment and cultural figures from the late 1990s through the mid-2000s, that nearly 100 percent of content from major internet portals and private websites from the first decade of China’s internet has now been obliterated. "No one has recognized a serious problem,” wrote He. “The Chinese-language internet is rapidly collapsing, and Chinese-language internet content predating the emergence of the mobile internet has almost entirely disappeared.”

Posted on Wednesday, May 22, He’s post had been removed from WeChat by the following day, yielding a 404 message that read: “This content violates regulations and cannot be viewed.”

Read the full story at the China Media Project.

NEWSMAKERS

No Taiwanese Allowed

How do you produce a passport for a country you’ve never been a citizen of? That was the impossible demand made of two Taiwanese journalists last week as they sought media credentials for the WHO’s World Health Assembly (WHA) in Geneva.

When Central News Agency (中央社) correspondents Judy Tseng (曾婷瑄 ) and Tien Hsi-ju (田習如) applied for press passes from the United Nations Media Accreditation and Liaison Unit, they were told they needed “Chinese passports” — passports, in other words, issued by the People’s Republic of China, which claims sovereignty over Taiwan but has never controlled the territory.

This, of course, is nothing new — in fact, it’s become something of a grim annual ritual in the Taiwanese media space. The country’s media has been excluded from UN proceedings since 1971, when a General Assembly vote awarded the seat representing China to the PRC. Chiang Kai-shek’s Republic of China on Taiwan was, effectively, expelled from the body, since it decided not to pursue alternative paths to UN membership that would involve renouncing its claims to represent all of China.

During the period of warming cross-strait ties under China-friendly president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九), Beijing deigned to allow Taipei to attend WHA proceedings as an observer. Since the election of Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) in 2016, however, China has been trying to isolate Taiwan from both its diplomatic allies and international institutions as collective punishment for not voting in its preferred candidates. Even as the country was lauded as a gold standard in public health during the coronavirus pandemic, it was barred from the UN health body. Annual campaigns to get back in have so far come to nought.

UN Principles VS the One China Principle

Journalists in Taiwan have been standing up for their colleagues’ right to report on these important meetings. The Association of Taiwan Journalists and the International Federation of Journalists called on the UN to let in Taiwanese reporters, condemning their exclusion as both a violation of press freedom and UN principles. The Taiwan Foreign Correspondents' Club also issued a statement blasting the WHA, and CNA has published a report arguing that "journalists do not represent officialdom, but exercise their duty and expose the truth on the basis of freedom of the press and the right to know.”

On the other side of the Taiwan Strait, China’s official press was less concerned about these principles and more intent on asserting its claims over Taiwan. CCP mouthpiece People’s Daily ran a report carrying statements by the State Council’s Taiwan Affairs Office, whose spokesperson Chen Binhua stressed that Taiwan’s exclusion from global health talks was a result of the ruling DPP’s “refusal to acknowledge the One China Principle of the 1992 consensus” (九二共識), referring to the post-facto name for an informal agreement between the CCP and Taiwan’s then-ruling KMT in 1992, prior to Taiwan’s democratization. Even to this day, both the CCP and the KMT disagree about what the “consensus” actually means.

Chen added that “Taiwan compatriots are our family and we always have their health and well-being at heart.” For Taiwan, trusting their people’s health and well-being to a country that only days ago released a simulated bombing of it for defying Beijing is just another impossible demand they have to meet.

CMP SHOWCASE

Understanding Xi's Push for a Surveillance Society

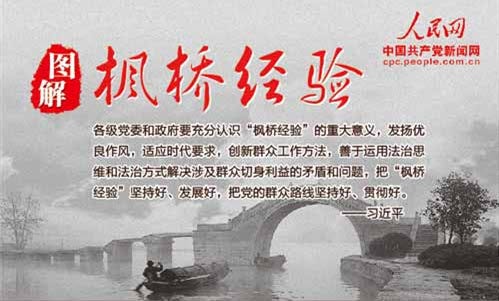

Over the weekend, the New York Times ran an informative in-depth report by Beijing correspondent Vivian Wang on China’s comprehensive and invasive approach to enforcing the social and political compliance of its population — an approach that combines technology and “innovative policing” with local governance models from the Chinese Communist Party’s past. The ultimate goal, as Wang writes, is “to embed the party so deeply in daily life that no trouble, no matter how seemingly minor or apolitical, can even arise.”

The China Media Project has closely followed these developments ever since they began taking shape nearly 11 years ago under the revived concept of the “Fengqiao experience” (枫桥经验), which dates back to 1963. Xi Jinping has intensively applied this concept to social governance ever since Party-state media hailed it’s 50th anniversary in 2013, at which time CMP posted a full history.

For those interested in learning more about “the Fengqiao experience in the New Era” and trends such as “grid-based management” (now also being applied to Hong Kong), please see our research below:

"China Under the Grid" — December 7, 2018

"A Rock Star's 'Fengiao Experience'" — November 30, 2018

"What Does Xi Mean by 'Rule of Law'?" — October 30, 2014

"Xi Jinping Plays With Fire" — October 17, 2013

In the CMP Dictionary:

“Fengqiao Experience” (枫桥经验)

“Chaoyang Masses” (朝阳群众)

“Grid-Based Management" (网格化管理)

“Smart Governance” (智治)

BUZZWORDS

Did You Catch that Catchphrase?

This week, China’s official People’s Daily newspaper and other Party-state media have been going on about an especially perplexing official buzzword (提法), one that translates poorly into other languages. In English, we’re choosing to call it the “Four Good Rural Roads” (四好农村路).

Say what now?

First introduced by Xi Jinping in March 2014 as an initiative to improve lives in rural areas and to turn China, as he said, into a “transportation power” (交通大国), the phrase is getting attention now because Xi recently relayed “important instructions” (see our dictionary) — an executive act that assures the issue gets top billing in propaganda outlets. It is also being pushed anew because this year marks the initiative’s tenth anniversary, and much CCP propaganda is structured around the all-important anniversary, which paints the policies and decisions of the leadership with a patina of momentousness.

But what does it mean?

This perplexingly framed buzzword encompasses the idea that the government must ensure that roads in rural areas are “built well” (建好), “managed well” (管好), “protected well” (护好), and “operated well” (运营好). The crux here is that at present many rural areas have huge problems of accessibility that impact the development of local economies. It’s a simple concept. But in China’s highly scripted political culture, all concepts need to be subjected to formulaic framing that packages policies for distribution throughout the bureaucracy and, often, associates them ritualistically with the leadership.

CMP IN THE HEADLINES

Working Past China’s Data Gaps

In a recent piece that incorporates insights from CMP researcher Alex Colville, RFA explores the growing problem of lack of access to key data resources by China researchers outside the country. The central theme of the report is that poor access to data is making it much harder for those studying China to understand what’s happening in such key areas as politics, society, and the media. And this runs the risk of warping global understanding of China at a time of growing conflict and misunderstanding.

Several of the experts interviewed for the article spoke about the need for greater creativity about how data is accessed and used. Independent researcher Kai von Carnap said he now uses more digital tools to extract data from China, such as natural language processing, or NLP.

Colville, whose research at CMP also involves developing homegrown databases, said: “I think we’re going to have to become more creative with the data we’re given.”

To take advantage of the research insights of the CMP team, consider becoming a paid subscriber to Lingua Sinica, which includes access to “CMP Toolkit,” regular premium posts about the Chinese media landscape and how we navigate it.