Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 23 October

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

This week we have a globe-trotting selection of stories covering some of the most interesting stories in Chinese-language media from Taiwan, Hong Kong, the PRC, and overseas Chinese communities.

Speaking of communities, I once again want to plug our sister publication Tian Jian (田間), a new outlet in Chinese that we hope can build a cross-regional conversation about journalism, media, and free speech in our complex world — where the fate of media and information integrity can often seem uncertain. On that score, I turn your attention to announced cuts in the newsroom at Malaysiakini (當今大馬), one of Southeast Asia’s brightest lights when it comes to public interest journalism. We touch on that story down below, but Tian Jian editor Chien Heng Yu dealt with it first in his Chinese newsletter yesterday.

Since the Lingua Sinica newsletter last found its way to your inboxes, Tian Jian has published more original pieces, including an interview with China Dialogue founder Isabel Hilton. Tian Jian is far from just a translated version of Lingua Sinica — it’s written by and for Chinese-language journalists, with the goal of building capacity in Sinophone media while showcasing our own top-notch journalism (which you’ll eventually read here at Lingua Sinica in translation.) If you read Chinese or are learning, definitely give it a follow. It’s 100 percent free, and will stay that way.

Until next time, enjoy!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

NEWSMAKERS

Guess Who’s Back

How’s this for a #ThrowbackThursday: Rui Chenggang (芮成钢), one of the most infamous broadcasters from China’s official CCTV, is out of prison and back on our screens after ten long years.

You might remember Rui from the 2010 G20 Summit in Seoul, when US President Barack Obama said he would give the final question at a press conference to South Korean media. Rui interrupted, saying "I'm actually Chinese, but I think I get to represent the entire Asia" (speaking of which, see Anti-Social section below). With his bombastic, nationalistic style, Rui was well ahead of the “Wolf Warrior” curve — and it stood out. By 2014, Rui had amassed millions of followers on social media and earned a reputation as the state broadcaster’s star anchor.

But that was the year it all came crashing down. News emerged that Rui was under investigation for corruption, but the man himself was nowhere to be seen, lost somewhere in the black box of China’s judicial system. In 2016, he was sentenced to six years in prison.

Rui was released in 2020 but maintained a low profile — until earlier this week, when he reappeared in a 17-minute YouTube video announcing, “Rui Chenggang is back.” Even if you’re not too excited to hear his voice again, the reception he’s received on the platform is still worth a click. “This isn’t CCTV,” one commenter wrote, “I expected you to say something human.”

“You haven’t changed at all,” agreed another. “Ten years in prison influenced you less than CCTV.”

BUZZWORDS

Hong Kong’s Whole-Process Democracy

Here at Lingua Sinica and the China Media Project, we’ve been monitoring an ongoing trend in Hong Kong that has accelerated since 2020 and the implementation of the national security law: the rapid adoption of political jargon from the mainland PRC, sometimes losing much in translation. Last week, we noticed the latest example of this. Whole-process democracy, a Xi buzzword now being used to describe Hong Kong’s “patriots-only” system, which since 2020 has effectively barred the political opposition and drastically reduced the number of directly elected lawmakers.

In mainland China, “whole process democracy” (全過程民主) is the idea that China has found a democratic system distinct from that in the West. Since 2021, Xi Jinping has been using the phrase to make the case before domestic audiences for the strength of China’s political system, as well as to throw off international criticism of China on human rights grounds. In Hong Kong, Tu Haiming (屠海鳴), vice-chair of a liaison group on Hong Kong policy for the CPPCC National Committee, says the city “already encompasses the fundamental elements of whole-process people’s democracy, while manifesting the unique characteristics of Hong Kong’s governance.”

Writing in Bauhinia Magazine (紫荊), a state-run publication we previously identified as a local analog to the CCP theoretical journal Qiushi (求是), Tu wrote that Hong Kong Chief Executive John Lee’s third policy address on October 19 demonstrated this perfectly. “Whole-process people’s democracy with Hong Kong characteristics requires the participation of every resident,” Tu wrote of the “consultation sessions” attended by Lee, who won office in an uncontested election in 2022, securing 99.4 percent of the vote among a 1,500-strong election committee.

When Tu’s article was translated into English and printed in the China Daily, there was one curious omission. In this version for international readers, Tu’s most audacious claim was missing: that Hong Kong’s past political unrest resulted from “blindly chasing Western-style democracy.” That might raise the eyebrows of anyone familiar with the 2014 Umbrella Movement or the 2019 anti-government protests, which were sparked not by too much democracy but by residents’ thwarted expectations for a meaningful say in how they are governed.

ANTI-SOCIAL

Bubbling Controversy

It was an unlikely venue for an international incident — and an even more unlikely topic. But on the Canadian version of reality show Dragon’s Den, where entrepreneurs pitch their business ideas to a panel of potential investors, a local bubble tea company Bobba managed to spark a proverbial culture war. The pair behind this Quebec-based venture told the panel that they were out to “disrupt” the market for the Taiwanese beverage that’s taken the world by storm.

Their pitch played into tired and harmful stereotypes about Asian food as unhealthy and unknowable — mysterious and potentially even dangerous. “You’re never quite sure about its content,” they said, claiming to have made a “healthier” (and alcoholic) version of the beloved beverage. The spirit of “Chinese Restaurant Syndrome” lives on. When one of the would-be investors, actor Simu Liu (劉思慕), raised the issue of cultural appropriation, Bobba’s founders said that the drink was "not an [ethnic] product anymore" and fair game for reinterpretation.

Liu characterized Bobba’s approach as "taking something that is very distinctly Asian in its identity and, quote-unquote, 'making it better.'" He wouldn’t feel comfortable, he said, backing a product that “profit[s] off of something that feels so dear to my cultural heritage.” Online, many took his side, prompting the company to issue a public apology and Liu to urge restraint.

Tempest in a Teacup

In the home of bubble tea, though, the conversation was markedly different. Many Taiwanese internet users chafed at the idea of Simu Liu, a Chinese Canadian, speaking for Taiwan and claiming bubble tea as a part of his cultural heritage. They also pushed back against the idea of boba belonging, broadly, to all Asians — it’s Taiwan’s, after all, not China’s, Japan’s or Korea’s. “He said [bubble tea] is from his hometown but he’s not Taiwanese,” read a popular comment on Taiwan’s FTV News. “Taiwan’s unique culture is not the common property of ‘Asians.’”

“All he cares about is Asians versus whites,” another wrote on Threads. “Asian Americans and Canadians say that bubble tea is their shared culture and Taiwanese should look at the big picture and fight against European and American cultural colonization, but they are appropriating [Taiwanese] culture themselves.” It’s natural for Taiwanese to reject hegemonic notions of “Chineseness” or “Asianness” imposed on them by outsiders, and to insist on the right to speak for themselves. They are all too used to regional bullies claiming to represent them, be it Japan in their half-century of colonial rule (a time when the empire weaponized the slogan “Asia for Asians” to brutalize their neighbors) or China in the present day.

It would be easy to dismiss the Taiwanese response as backwardness, born from ignorance about the minority experience and the harms of cultural appropriation — or the North American response as another example of culture-war groupthink. But both would be vast oversimplifications. For Asian diasporic communities in the West, boba/bubble tea (words, tellingly, not common in Taiwan itself) has become symbolic of a shared experience for Asians of various backgrounds, its mainstream success a symbol of Asian cultures’ growing acceptance. For Taiwanese, pearl milk tea (珍奶) and other hand-shaken drinks (手搖飲) are a Taiwanese soft power triumph, a way that they have achieved a form of worldwide recognition.

These discrepancies between the dominant discourses in Taiwan and North America do not prove that either is wrong. Rather, they remind us that, even in discussions about globalization and the clash of civilizations, local concerns and conditions are always what matters most.

FLASHPOINTS

Something Rotten in the Province of Yunnan

Last week, students at a fee-paying, private school in Yunnan province began falling ill, complaining of stomach aches and digestive issues. As parents shared their problems in WeChat groups, a pattern quickly emerged. Something must be rotten in the school canteen.

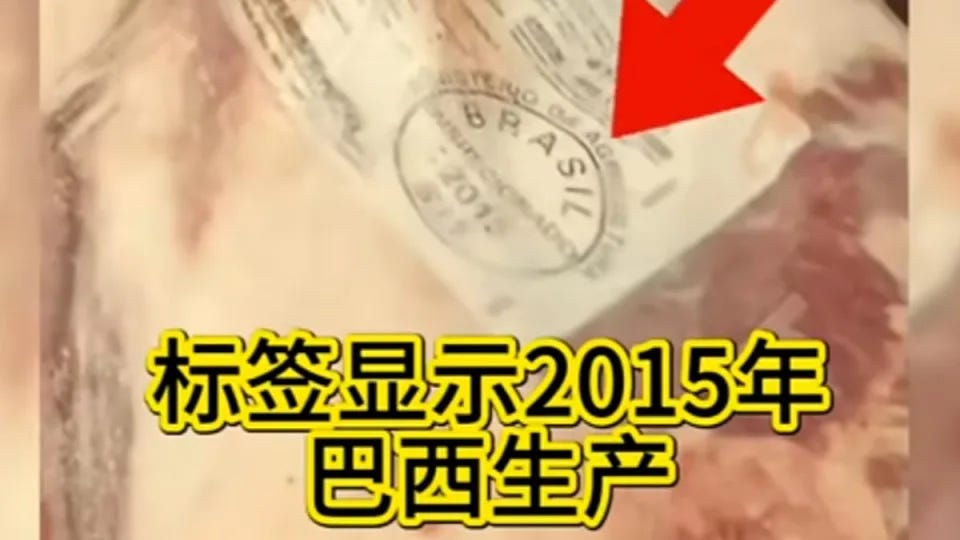

The story, which became known as the “Stinky Meat Incident” (臭肉事件), developed rapidly over the days that followed, the latest in a spate of recent cases in China concerning food safety. School administrators met with parents in a move that aimed to reassure but had the opposite effect. Fuming at a vice principal pictured with a smile on her face and feeling like they were not taken seriously, the parents forced their way into the canteen to inspect the ingredients for themselves, broadcasting their live investigation on their phones. They all agreed the meat smelt off, and at one point found what they thought was a smoking gun: a packet of frozen meat from Brazil with the year 2015 printed on it. Was this supposedly fancy school in fact serving their children decade-year-old “zombie meat?”

As it happens, no. The label, printed in Portuguese, referred not to the date of production of expiry but to the company’s export registration certificate. But the dramatics were enough to catch the attention of local officials, who launched their own investigation and found that the meat had been improperly transported. The parents were right about the meat smelling bad. The headmaster was forced to step down, with the school and its caterers facing steep fines.

The “Stinky Meat Incident” is not the only food safety scandal to rock China this summer. In July, we were the first to bring a rare exposé about improperly transported cooking oil to English-language audiences. Earlier that month, the state-run Beijing News (新京報) reported that the state-run grain stockpiler Sinograin was using the same tanker trucks to transport both fuel and food oil products, forgoing any cleaning process in between. Their investigation kicked up a national scandal that rapidly became a global news story, spurring decisive official action.

The contours of the “Stinky Meat Incident” aren’t quite the same. The case was not unearthed by an official outlet like the Beijing News but rather concerned parents on social media. Still, both provide examples of behavior normally punished in China — be it investigative journalism or self-media vigilantism exacerbated by misinformation — being rewarded. Food safety concerns are seeing a national resurgence and are serving as perhaps the only front left to hold power to account.

MEDIA MOVES

Cuts at Malaysiakini

Under commercial pressure: news and views that matter

Our Chinese-language sister outlet, Tian Jian (田間), which focuses on issues of media capacity and professionalism, reports on changes announced this month at Malaysiakini (當今大馬), one of Malaysia’s leading professional online media. On October 11, Malaysiakini issued a statement saying it was undergoing reorganization in the face of the same shocks that have faced the media industry globally. The outlet said that it was not shutting its doors, but that it would be cutting staff. The moves, said the statement, would “ensure future operational stability and success” (确保未来运作稳定与成功).

Malaysiakini did not say how deep the cuts would be but advised some staff members to apply for positions at sister company FG Media. For journalists at the outlet, which in the past has won numerous news awards, that could be a bitter prospect. FG Media’s model is not about journalism, but rather about public relations and marketing services, including native advertising — meaning paid-for ads that are seamlessly assimilated with other content on platforms like Malaysiakini and its video channel, KiniTV. Meanwhile, Malaysiakini executive editor RK Anand and chief operating officer Tham Seen Hau said the outlet’s content would not be affected and subscriptions and donations would help it continue to grow.

Malaysiakini was founded in 1999 by Steven Gan and Premesh Chandran, both former journalists from Malaysia's The Sun. It provides coverage in four languages, including Malay, Chinese, English and Tamil. At a time when many media are dominated by politicians and businessmen and are subject to various forms of censorship, Malaysiakini has been a crucial independent professional media outlet in the country. Its motto: “News and views that matter.”

STORYTELLERS

Who’s Studying Journalism in China?

It is no secret that China’s news cycle has been coming under ever stricter controls, with fewer investigative stories and more outlets resigned to reprinting the Party line, verbatim, on important events. But less known is how these darkening prospects have impacted the next generation of journalists.

In one of their latest podcast episodes, Singapore-based Initium Media interviewed reporter Liang Yutong (梁嶼桐), who studied journalism in China and has been speaking with current j-school students and instructors about the state of the country’s campus journalism. According to Liang, journalism was a highly competitive subject ten years ago. Back then, aspiring journos were inspired by legendary CCTV anchor Chai Jing’s memoir What I Have Seen (看见), actively going out into the field and pushing the limits of what was possible. Magazines under university journalism departments were run by professional editors who challenged official red lines whenever they could, and made valuable contributions to civic dialogue and collective memory.

Today, Chai Jing’s memoir is banned. Liang notes a “synchronized” takeover of student publications, beginning in 2017, by technocratic enforcers. Journalism programs are now mainly an option for students to enroll in only if their first choice is full. Liang also believes that education reforms in 2019 and 2021, namely the increase in political education in high schools and universities, have impacted the new cohort’s values. Asked what their favorite outlets were, freshmen said Xinhua or People’s Daily, telling Liang they wanted to serve as “mouthpieces.”

Today, many journalism students are simply lying flat. “In the past few years,” says Liang, student journalists “have gone from reporting on a story even if they can't publish it to knowing it’s impossible to publish and just not trying to do it at all.”

DID YOU KNOW?

Dong-Dong Dailies

Over Taiwan’s forty years of authoritarian rule and political repression — a period known as the White Terror — dissidents were routinely executed or jailed for much of their lives at institutions like Jingmei Military Detention Center in Taipei (now the Jing-Mei White Terror Memorial Park). For years or decades at a time, their only connections to events taking place in the outside world were heavily censored newspapers printed by the Party-state that had imprisoned them.

With characteristically Taiwanese flair, though, even this dark reality has a catchy, cute name: the papers were called dong-dong bao (洞洞報), or “hole-hole dailies.” This was because politically sensitive articles were simply snipped out, leaving gaping holes scattered throughout. This degree of censorship was deemed necessary even though the only newspaper prisoners got was the Central Daily News (中央日報) published by the ruling Kuomintang (中國國民黨).

For some political prisoners, though, there were other opportunities to keep up with current affairs. At the Green Island penal colony off the coast of eastern Taiwan (now a memorial park), some got to make the 33-kilometer trip across the powerful Kuroshio Current to Taitung, where they would buy food for other prisoners — including freshly caught fish, innocently wrapped in that day’s newspaper. Back on Green Island, these fishy broadsheets were other prisoners’ only window on the world.

(OVER)REACTIONS

Café Contempt

Hurting the feelings of the Chinese diner?

The Chinese social media and e-commerce platform Xiaohongshu (小紅書) has been described as "China's Instagram." But the latter is far less prone to fits of outrage and controversy than its often-simmering Chinese counterpart — which apparently has some very sensitive souls in its user base of more than 300 million monthly active users.

The platform turned its tender side last week as it fumed over a Hong Kong-related controversy that really wasn’t. At issue was a sign posted outside a diner in the still very bilingual city that noted mealtime time limits in both Chinese and English. In Hong Kong’s busy dining-out culture it is customary for restaurants to place a mealtime limit on customers of about 45-60 minutes, particularly during peak times, ensuring that diners do not linger and drive down turnover. In this case, however, the sign outside of one Hong Kong diner, posted to Xiaohongshu, seemed to specify a 30-minute dining limit in Chinese and a 40-minute dining time in English. Oops.

A Bit Excessive

The sign with its certainly innocent typo quickly went viral after it was posted by a Chinese netizen under the title, “A bit excessive” (有點過分了). Debate raged between those who found the sign deeply discriminatory, and those who felt this was an over-reaction. “The place I most refuse to go in China is Hong Kong,” wrote one furious Xiaohongshu user. “It’s like any time we mainlanders go, we’ll get discriminated against no matter what. I spend my money and get hatred in return.”

One of a number of outlets to report on the ruckus, HK01 noted that under Hong Kong’s Race Discrimination Ordinance (RDO), which would apply in cases like this one, it is “unlawful to discriminate, harass or vilify a person on the ground of his/her race in prescribed areas of activities,” including the provision of goods and services.

CHAIN REACTIONS

Who is Wuhan Plus?

Another “cute” proxy has escaped labeling as an official government account.

When the social media account Wuhan Plus surpassed two million followers on Facebook in late June, it sent a thank you message to its followers: “We appreciate all the love and care from our followers and everyone that consistently supports our efforts!” Three months later, the Wuhan Plus account claims another 100,000 followers. But who is this account exactly?

In fact, though Wuhan Plus carries no label on Facebook, it is operated by the Chinese government-run China Daily in cooperation with the city of Wuhan and its Changjiang International Communication Center (CICC), under the local propaganda office and the city’s state-run Wuhan Media Group (武汉广播电视台). China Daily’s cooperation with the CICC, which was announced as part of the center’s launch last year, is an example of how China’s new national strategy for broadening external propaganda efforts with provincial and city involvement is being coordinated with central-level agencies and media (for more, see this week’s “Going Global”).

Tourism, Plus Praise for the Chinese Model

The Wuhan Plus accounts on Facebook, YouTube and X focus on coverage of sports, tourism and culture in the city. But these relatively benign posts are interspersed with clear propaganda messaging. Examples include this video interview by CICC with Bangladeshi scholar Mostak Ahamed Galib from the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT), which parrots state narratives in promoting China’s development vision for the world, with leading questions from the CICC anchor. Galib, who is identified in the video and frequent reports in central state media as “executive director of the cross-cultural communication and Belt and Road Initiative research center” at WUT, works as a lecturer at the university’s School of Marxism, where he teaches courses on the BRI. A profile of Galib on the School of Marxism website says that he has assiduously studied Lei Feng (雷锋), the supposedly selfless People’s Liberation Army soldier who was the focus of several propaganda campaigns in China in the 1960s. Galib’s colleagues at the university reportedly call him a “foreign Lei Feng” (洋雷锋).

GOING GLOBAL

From Hunan to Africa

Looking for powerful voices for overseas propaganda, China’s leadership has turned to provincial broadcast powerhouses like Hunan TV.

Last week, Chinese state media and government officials gathered in Changsha, the capital of Hunan province, for the country's annual China New Media Conference (CNMC), where this year's theme was, "Building a more effective international communication system." What does that mean? Essentially, it is about the renewed push under Xi Jinping since 2021 to strengthen Chinese “discourse power” abroad, and shore up what it calls “external propaganda” (外宣), by building a network of provincial and city-level international communication centers (ICCs).

These centers, directed in most cases by local propaganda offices, draw on the immense resources vested in provincial-level media groups, which have actively commercialized — and to various extents, professionalized — over the past 25 years. One prime example is the Changsha-based Hunan TV, which under the guidance of the province’s Hunan International Communication Center (HICC) has developed a television channel venture in Africa called “Golden Mango” (金芒果) that now claims 10 million satellite users. Hunan TV was a pioneer of the possibilities of commercial television in the 2000s, spawning hits like the song competition show “Super Girl” (超级女声).

In a speech to the Changsha event, Opoku James White, a host and deputy editor-in-chief of “Golden Mango” in Ghana, said that “people in many African countries have a very limited understanding of China, and many of them learn about China every day through the BBC, CNN and other media or social media platforms, where some of the contents may not be objective.” By contrast, the host told the government-run China Daily that his channel "disseminates objective information" while offering television shopping and e-commerce. According to China’s official view of “objectivity” in a media context, the term refers concretely to coverage that is uncritical, befitting the global objectives of the leadership.

SOURCE CODE

Reading RED on Cross-Strait Relations

Last week in Beijing, more than 80 scholars and officials attended a grand ceremony to drive home the simple point that Taiwan is an inalienable part of China. The event centered on a new book by Taiwanese author Fan Wenyi (范文议) whose title read like a brawling challenge — Who Says Taiwan is Not Part of China? (谁说台湾不是中国的). According to state media coverage, Fan’s book, which makes the case for reunification, will have “a positive significance in enhancing mutual understanding and trust between compatriots on both sides of the Taiwan Straits."

But on that account, a deeper dive behind the headlines turns up more questions than answers.

Fan Who?

While PRC media coverage presents “Professor Fan Wenyi” as a known scholar born in the city of Hualien in eastern Taiwan, virtually no information is available about the man, pictured by the China Youth Daily, China News Service and others as an elderly man in glasses, wearing an oversized gray suit. Aside from a smattering of official media mentions prior to this book launch — like this quote in the Chinese government’s own Taiwan.cn — Fan Wenyi seems to be a nobody. Last week’s coverage explains that Fan's mother was an active member of literary societies during the Japanese colonial era in Taiwan, and that she instilled in him a sense of his fundamental Chineseness. But the scholarship of this “research scholar” is nowhere to be found. Nor is it clear where he was ever a professor. And yet, audiences are meant to be moved by his authoritative declaration: “I am Taiwanese, and I am also Chinese.”

What Book?

On the question of audience, the even odder fact is that Fan’s book, launched with so much fanfare within a week of Taiwan’s national day holiday, is apparently available nowhere. For starters, bookstores and suppliers in Taiwan, including the well-known Eslite, do not carry the book at all. Even on Douban (豆瓣), China’s popular domestic online book supplier, there is no whiff of Fan’s work. The only online source — oddly for a book meant to “enhance mutual understanding” on both sides of the Taiwan Straits — appears to be Amazon Singapore, where the book is “currently unavailable.”

In fact, the Beijing event is quite typical of how China’s leadership seeks to push agendas such as Taiwan reunification with unchanging central themes (good feeling among compatriots) pushed through centrally-planned events, which are then promoted through central media.