Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 2 Nov

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica:

This is the last time Lingua Sinica will be going out on both MailChimp and Substack. Going forward, we’ll be moving entirely to the latter, which you can subscribe to here. After just a week on the platform, our Substack subscribers already outnumber subscribers to our e-mail newsletter, and although we’re still finding our feet we hope it will soon provide a space for more regular content and discussion.

The news of former premier Li Keqiang’s passing — despite official attempts to downplay public mourning — has dominated much of the Chinese-speaking world over the past two weeks, and for that reason figures predominantly in this issue. In Redlines, we look at the official response from Beijing, while in Spotlight we turn an eye to Chinese-language coverage outside the PRC mainland.

Across the Taiwan Strait, however, election fever is the talk of the town. Press speculation has been swirling about a possible joint ticket between the opposition’s top presidential candidates: Hou Yu-ih of the KMT and Ko Wen-je of the TPP. Together, they could command enough support to throw the ruling DPP out of office.

At a press conference organized by the Taiwan Foreign Correspondents Club last week, I got to see Ko in action for the first time. His sometimes curt and awkward style was a far cry from the polished (in uninspiring) manner of the DPP’s Lai Ching-te. When he spoke of the political gridlock in Taiwan, though, I could see some of his appeal shining through: Everything in Taiwan, he bemoaned, is about unification or independence. Meanwhile, wages are stagnant and rent is skyrocketing — it’s time to break through the green vs blue political divide, he said, and solve the real issues affecting people’s livelihoods.

But as much as many Taiwanese would love to stop worrying about the existential threat next door and get on with it, is that even possible? Unfortunately, the former doctor’s prognosis of the problem is not as compelling as his diagnosis. In place of a coherent ideology, his party and campaign seem hyper-focused on the divisive man himself. Look out for more on Taiwan’s January election and how it’s being covered in future editions.

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

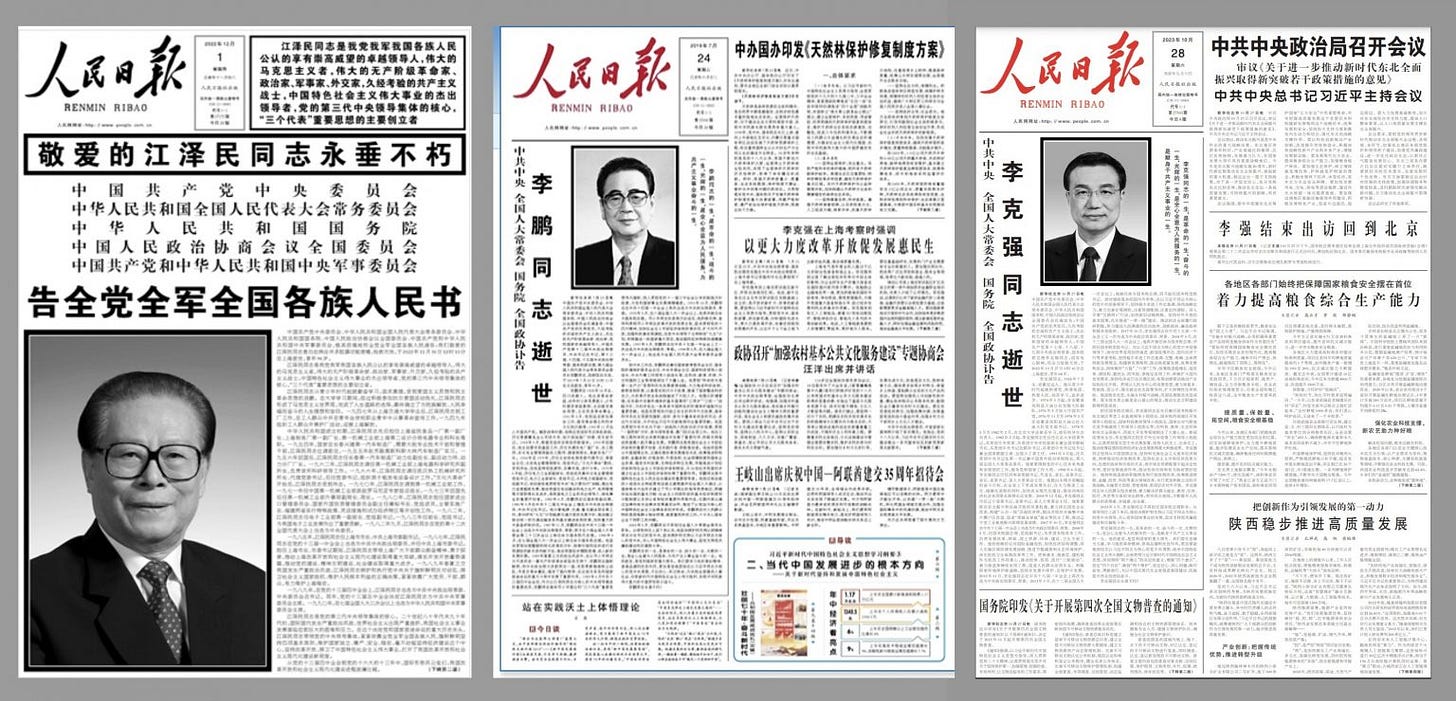

Sidelined in Death

As the news broke internationally last Friday of the death of former Chinese Premier Li Keqiang (李克强), one word in the headlines seemed to condense the political significance of his passing. That word was “sidelined.” Many outlets outside China told the story of a determined reformer, a “moderate technocrat,” who had been increasingly shoved aside over the past decade as Xi Jinping showered himself with glory — and surrounded himself with the kind of yes-men Li was not.

As news of Li’s death emerged, China’s leadership sought to contain any possible political fallout from the death of the popular former premier who, from time to time, could surprise with his frankness on issues such as poverty. As a result, Li Keqiang has been sidelined in death this week just as he was in recent years within China’s top leadership. For an in-depth look at the official handling of Li’s death and the lessons it holds about Chinese politics more broadly, read David Bandurski’s thoughtful analysis.

SPOTLIGHT

Li Keqiang's Death in Regional Media

Who was Li Keqiang, and what is the significance of his death late last week? As we explain in our Redlines section, there has been near silence on these questions inside China. But Chinese-language media outside the country, and across the region, have offered more context. Our top selections:

From 'Wall Breaker' to 'Invisible Man': The Late Li Keqiang, and His 10 Years as China’s Premier (從「破壁者」到「隱形人」:逝者李克強,和他擔任總理的中國十年) — Initium (端傳媒)

This thoughtful and incisive look back on Li Keqiang begins in 2012, with Li as a new premier following in the footsteps of Wen Jiabao, and China at a crossroads — “a country that was powerful, but also struggling and confused.” A host of problems needed resolving, from rampant corruption to widespread social unrest. But just a short way into the new administration, it was clear Premier Li was being sidelined in critical ways, and that Xi Jinping was climbing to the detriment of collective leadership. On this point, Initium cites research from CMP co-founder Qian Gang (钱钢), who showed how Li no longer by the end of 2013 issued “important instructions” (重要指示), which became the exclusive prerogative of Xi. For more on “Important Instructions” check out our CMP Dictionary. Pulling no punches, Initium says straight away in its teaser that it cannot be said that Li had many accomplishments during his tenure, though he was one “who occasionally tried to struggle.”

Judging Li Keqiang's Political Base Color from Two Events that Profoundly Changed China** **(從深刻改變中國的兩件事看李克強的政治底色) — HK01 (香港01)

Want to plumb the shallows of what Li Keqiang managed to accomplish as he was sidelined for 10 years? HK01, the Hong Kong-based online news portal created in 2015 by former Ming Pao chairman Yu Pun-hoi (於品海), seems to deliver a back-handed compliment as it overpromises with two things under Li that “profoundly changed China.” The first the article cites is WeChat, the everything-under-the-sun social media platform that has indeed transformed life for many Chinese. HK01 suggests that Li had some role in paving the way for the platform, quoting his remarks from June 2017: “When WeChat first appeared a few years ago, there was a lot of opposition from many sides [in the government], but we resisted such voices and decided to ‘take a look' before regulating it. If we had continued to regulate it the old way, we might not have WeChat today!” Thank you, Premier Li? Next, HK01 gives Li credit for China’s booming delivery industry, essentially making the same argument — that as head of government, he might just as well have killed it. The outlet concludes: “Li Keqiang's attitude towards WeChat and the express delivery industry shows that he was a tolerant and prudent politician.”

DID YOU KNOW?

Enduring Faith in the Benevolent Official

As the CCP leadership sought to constrain public mourning for the former Premier Li Keqiang following his death last Friday, ordinary Chinese found numerous ways to pay their respects. Many remembered Li as a compassionate official, solicitous of the needs of the people. But in some instances, like this one posted to Twitter by “Teacher Li is Not Your Teacher” (李老师不是你老是), the grief expressed was so extreme it could appear oddly, even uncomfortably, histrionical to outsiders.

Why is the grief so extreme?

Part of the answer has to do with the deep historical intersection in China between grief and grievance. Owing to a lack of strong and democratic supporting institutions, including rule of law, ordinary Chinese facing injustice have come to see hope for redress in the figure of the benevolent official. The popular image of this official is the historical figure Bao Zheng (包拯), also known as Bao Gong (包公), a Chinese politician from the Song Dynasty who was renowned for his great integrity. Bao is given the fond title “Justice Bao,” or Bao Qingtian (包青天).

The deep-seated belief in intervention from on high has to a great extent been institutionalized through China’s system of “letters and calls,” known generally as petitioning, or shangfang (上方) — dealt with in detail in our CMP Dictionary. For many, petitioning directly to higher government officials has become the path of choice in redressing wrongs. This means that central government officials, and particularly the premier, can often be seen as present-day Justice Baos.

With Li Keqiang’s passing, have the Chinese people lost a leading figure of benevolence in the midst of hard and uncompromising power?

For some, Li may be celebrated in this way. But there is a deeper dilemma behind the Justice Bao phenomenon. If justice is vested in the goodness of the individual official, rather than demanded as a matter of legal and democratic process, that goodness arises from the same soil as repression and corruption. Justice Bao, in other words, is a product of the repressive and capricious system — a “classic manifestation,” as one Chinese scholar writes, “of the rule-of-man complex” (人治情结).

Be on the lookout next week for our more in-depth exploration at CMP of this intersection of history, politics, justice — and grief.

ON A LIGHTER NOTE

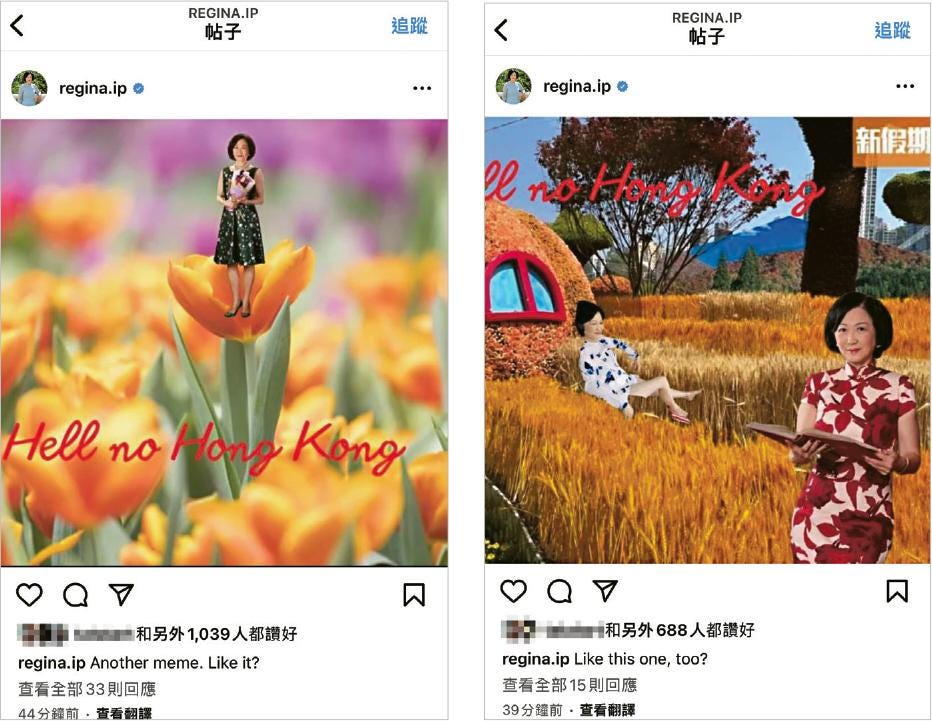

The political fortunes of Hong Kong’s most memed politician are a portrait of the city’s thwarted ambitions.

Local meme pages and irreverent expat groups alike in Hong Kong are full of tongue-in-cheek tributes to Regina Ip (葉劉淑儀), the long-time lawmaker who today is a member of the SAR’s Legislative Council and Convenor of its cabinet, the Executive Council.

In one image, posted around the time the Xinjiang forced-labor controversy swirled, she stares disapprovingly at her collection of luxury scarves. In another, she seems imperious as she enjoys a foot massage in Thailand. And in image after image online, she wears a dazzling array of holiday-themed cheongsams — which have become her signature.

Are the online tributes to Ip genuinely admiring, eye-rolling, or meta-ironic? It is often hard to tell.

But there is real and revealing irony in the fact that, despite her level of exposure and her popularity both online and in the polls, the politically ambitious Ip has never been able to climb to the top politically — even with her unflinchingly pro-Beijing politics.

The most dramatic and infamous moment in her career came a full two decades ago in 2003 when she attempted, as Secretary for Security, to push through national security legislation under Article 23 of the Basic Law. The deeply unpopular move drew half a million people to the streets and resulted in the withdrawal of the proposed law and Ip’s resignation. Despite the setback, however, Ip has managed to fail up, founding her own political party in 2011 and achieving impressive results in elections that at that time were actually competitive (a far cry from today).

Too popular for Beijing?

In a meaningfully democratic system, Ip’s visibility (and electoral track record) might have made her a top contender for Government House.

It was always clear that she aimed higher than the Legislative Council, and her interest in the city’s top job, the Chief Executive (CE), is no secret. In 2012 and 2017 she launched abortive campaigns for the post, before ultimately being edged by Beijing’s preferred candidates in the tightly controlled selection process.

In recent years, the Central Government has shown a pronounced preference for pliable functionaries over aspiring leaders with broad popular appeal and independent power bases. This was illustrated clearly in the 2017 race between the stone-faced career bureaucrat Carrie Lam and the more popular John Tsang, who had served as Financial Secretary. Tsang was able to drum up enthusiasm and draw crowds to his rallies, a rarity for a CE candidate. But the Beijing leadership decided a plain vanilla candidate would put Hong Kong politics in safer hands.

If Tsang's relative popularity was undesirable for China’s leadership, Ip’s viral potential is almost certainly regarded as a danger, however loyal she may seem. In this way, whatever the nature of her popularity, her unfulfilled political ambitions reflect the thwarted hopes of all Hongkongers who have yearned for a real say in how they governed.

One can read In Ip’s ludicrous photo shoots a kind of resignation. Surely, she knows this is not the public image of a serious politician — but, just as surely, she no longer cares. She may be in it just for the likes. And memesters may be in it just for the LOLs. But all seem to agree on one point: Hong Kong politics have become little more than spectacle.

NEWSPEAK

“Soul and root” has long been used as a metaphor for China’s rich cultural heritage. It is often invoked, for example, as the connective tissue tying both sides of the Taiwan Strait together. President Xi Jinping has for years used “soul and root” as a stand-in for cultural heritage, and as recently as summer 2022 likened China’s history and traditional culture to its “soul and root.”

A year later, however, the phrase acquired a new and more prescriptive meaning. At a Politburo study session in June 2023, Xi said, “We must not abandon Marxism as our soul or China’s excellent traditional culture as our root.” Just weeks after this new framing of “soul and root” was presented to the nation, bringing Marx into the picture, transportation workers across the northeastern province of Jilin participated in an array of activities to mark the 102nd anniversary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party themed around “safeguarding the soul and root.”

This new designation of Marx as the source of China’s soul and traditional culture as its root is a visual representation of Xi’s theory of the Two Combines (兩個結合), which adds a new prerogative to “combine Marxist theory with China’s outstanding traditional culture” to the one long established by Deng Xiaoping that Marxism must bend to China’s material conditions.

Why one is the soul and which the root? Find out in the CMP Dictionary’s latest entry for “soul and root.”

GOING GLOBAL

From Desert Power to Discourse Power

Lanzhou, the capital of northwest China’s Gansu province, is a city defined by its geography. Sandwiched between the Yellow River and the jagged, arid mountains of the Loess Plateau, its footprint is long and narrow — a stark contrast to the urban sprawl of other cities. That is why, when the local government sought space to build out, they had to look to another valley far to the north. Even there, hundreds of mountains had to be flattened and villages bulldozed to make way for the Lanzhou New Area (LNA), a satellite city built for a million people but currently home to fewer than half that.

Yet this underwhelming development at the foot of the Gobi Desert has become home to the latest outpost of China’s International Communication Centers (国际传播中心). ICCs, as we have documented elsewhere, are a recent but growing trend in the country’s external propaganda network. Typically formed by provincial and sometimes municipal level governments, they embody how Xi’s dictum to “tell the China story well” has become a whole-of-society effort, no longer the exclusive domain of national-level institutions like the Central Propaganda Department and state-run media like Xinhua and CGTN.

The fact that the Lanzhou New Area has been included in the ongoing devolution of China’s mission to tell “good stories,” however, is an instructive example of how far down this trend turning local resources toward buffing Beijing’s image has permeated. Nowhere, it seems, is too small to engage in international propaganda.

Dig deeper with our latest piece “Desert Power, Discourse Power.”

STORYTELLERS

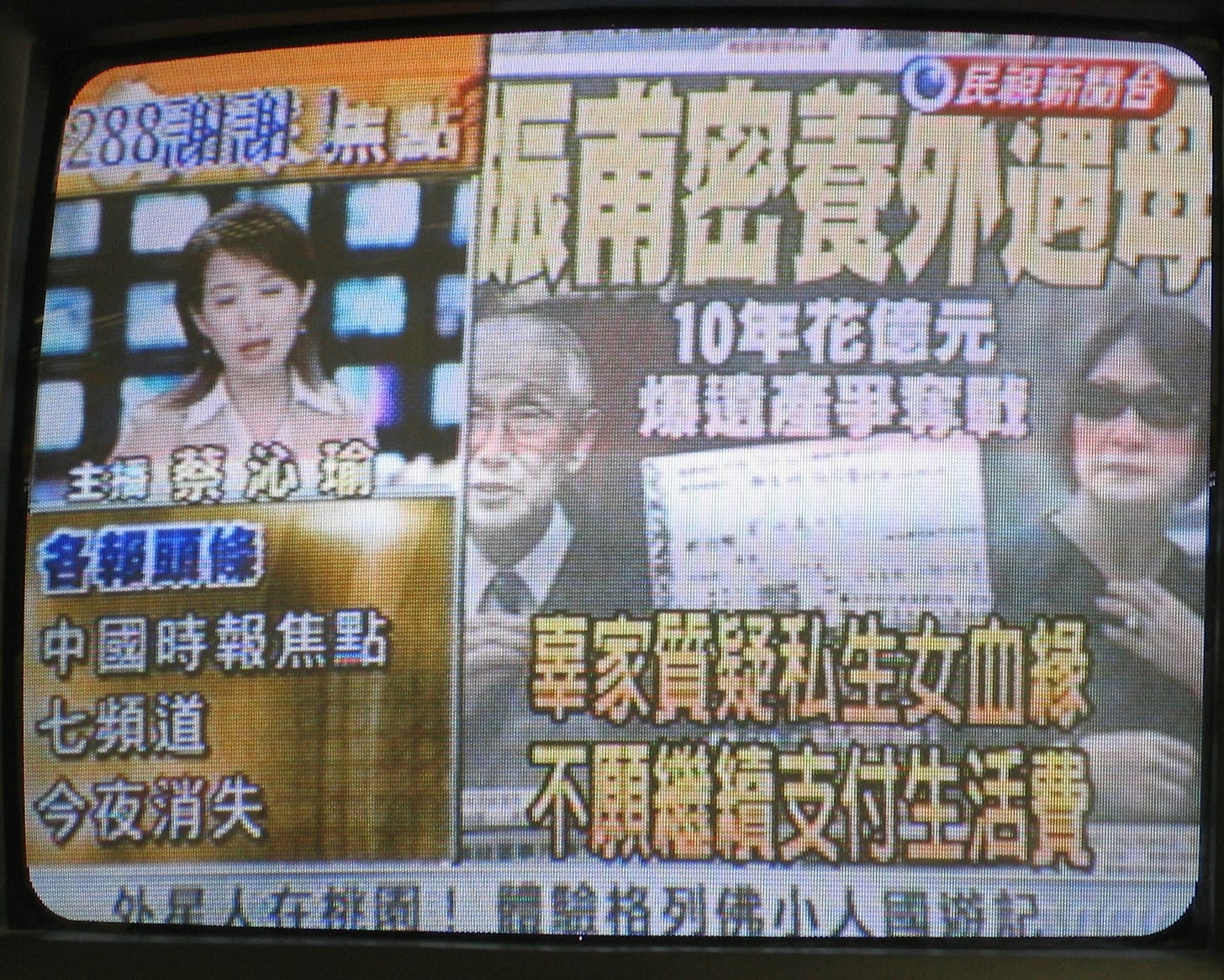

Fixing Journalism in Taiwan

The following is an excerpt from “Fixing Journalism in Taiwan,” a reflection by researcher and fixer Xin-Yun Wu on the opportunities and challenges of working with foreign media in Taiwan. Expulsions from China and growing international attention on Taiwan has seen an influx in foreign correspondents to the country — what can local journalists learn from them, and what do they, in turn, need to learn about Taiwan? Find out in the full piece next week.

It’s no secret that most mainstream media in Taiwan have been accused of poor ethics and lack of credibility. Working as a researcher for Clarissa Wei and Ivy Chen’s new cookbook Made in Taiwan, the most common question I got from restaurant owners was whether they needed to pay us for interviews. Jenjey Chen, vice president of Taiwan’s official Central News Agency, confirmed my suspicion: “Many media outlets in Taiwan do embedded marketing stories, especially TV channels. Why did they make a video about this vermicelli noodle stand instead of the other one? It’s usually because they paid.”

Taiwan, with a population of 23 million, has eight 24-hour news channels, most of them privately owned. Not unlike other places, this highly saturated and competitive media environment leads to sensationalist clickbait-oriented journalism. However, Taiwanese media generally have little interest in reporting international news. This insular outlook means some journalists are unhappy with the newcomers.

Why did they make a video about this vermicelli noodle stand instead of the other one? It’s usually because they paid.

Afore Hsieh, a Taiwanese journalist who now works as a fixer, told me that most local journalists who have worked in the same field for years develop their own ecosystems. She has heard complaints from video journalists who feel like fixers and journalists who work for international outlets parachuted onto the scene without understanding the rules or trying to fit in. Joan, another Taiwanese journalist who works for a US outlet, told me, “It can be frustrating to [local journalists] when you have been working on your connections within the semiconductor industry for years and suddenly all these foreign journalists show up and all request to interview TSMC.”

While some excellent stories are told by foreign correspondents, many reporting teams come to Taiwan with a presupposed narrative. For example, I’ve spoken to the same group more than five times with various media outlets. As a fellow fixer, Afore Hsieh also shares the same feeling. “The demand was very high last year after Pelosi came,” she says. “They mostly want a trip to Kinmen [a Taiwan-controlled island just off the Chinese coast], some kind of introduction to semiconductors, and people who will talk about their identity. I understand these were some of the most important topics at that time, but as a fixer, you start asking why they all want similar angles.”

CHAIN REACTIONS

Thank You Very Much, Henry.

Last week, Joseph Nye, the American political scientist credited for pioneering the theory of soft power, was in Beijing to attend the 8th China Global Think Tank Innovation Forum, where he spoke about the state of international relations today, challenging simple notions of “multipolarity” and cautioning over the use of misleading frames such as the “metaphor of the Cold War.”

The think tank event has been hosted since 2016 by the Center for China and Globalization (CCG), a Chinese think tank registered as a non-governmental organization and founded by Huiyao (Henry) Wang (王輝耀), a man who over the past decade has been at the center of global engagement with China. In his remarks to the forum (full-text here), Nye expressed his thanks to Wang and congratulated him “on gathering such a distinguished group of think tanks.”

But who is Huiyao (Henry) Wang?

Wang was the source of some controversy in 2018 after he was invited to participate in a dialogue with prominent IR scholars hosted by the Wilson Center, a nonpartisan think tank in Washington. The center was taken to task by US Senator Marco Rubio, who raised the issue of Wang's alleged connection to the United Front Work Department (UFWD), the CCP agency that oversees influence operations seeking to engage and co-opt individuals and organizations. Indeed, Wang’s bios inside China have long been clear about his associations, including serving as a director (理事) for the China Overseas Friendship Association (中华海外联谊会), or COFA, which is a bureau of the UFWD.

After Foreign Policy reported on the controversy, Wang’s CCG responded to the allegations, saying that “the article does not accurately reflect how nonprofits work in China.” It is simply a fact, the release said, that “civil society organizations are required to be registered by various levels of the Chinese government,” and it compared this process to US-based non-profits applying for 501 status with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). The response from the CCG was highly disingenuous on this point. Sure, US non-profits are required to register with the IRS, a matter of their tax exempt status. But Chinese non-governmental organizations are not just registered (注册) with various government ministries — as COFA with the UFWD — but are directly “supervised” (主管) by them. The current head of COFA, in fact, is UFWD chief Shi Taifeng (石泰峰), a member of the CCP Politburo who Chinese-language media outside the PRC have reported is the most powerful UFWD leader in decades owing to an enlargement of the department’s role under Xi Jinping.

A post from CCG said the event last week was hosted jointly with the University of Pennsylvania‘s Think Tank and Civil Society Program, which according to its LinkedIn page seeks to “strengthen democratic institutions and civil societies around the world.” However, the now CCG-linked newsletter Pekingnology reported that the event was also co-organized with the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (中国人民对外友好协会), or CPAFFC.

Let’s unwind that one for you.

The CPAFFC, well known to be a CCP-led front organization, is directly under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), and though part of the government has long been the spearhead of what the leadership calls “non-governmental diplomacy” (民间外交), or “people-to-people” (人与人之间) ties. Since August this year, the association has been led by Yang Wanming (楊萬明), who is also currently deputy director of the Hong Kong and Macao Affairs Office of the State Council (and a former ambassador to Chile, Argentina and Brazil).

Should you engage with China? Certainly. But be absolutely clear who you are dealing with, and how the links in the chain connect.

CMP SHOWCASE

China's Fake Press Problem

News extortion has persisted in China since the rise of the commercialized media industry in the mid-1990s. The idea behind the practice is frightfully simple, and the practice frightfully common, though cases are rarely reported in China’s media and the true scale of the problem is unknown. Essentially, media dangle the threat of negative revelations in front of a company or individual before presenting paid-for silence as an alternative path. Despite decades of official attention to news extortion, including regular government campaigns and notices (some lumping the practice together with “critical reporting”), cases are by all accounts staggeringly commonplace.

Over the past few months, local governments from the cities of Heihe and Zhaodong in the north, close to the Russian border, to Zhoukou in the central province of Henan, down to Yunnan in the country’s southwest, have all issued various statements, campaigns or cases involving news extortion. This year and last, the China Association for Public Companies (中国上市公司协会) warned listed companies to be alert to the practice, even dealing with the issue in a closed-door session in April with senior propaganda officials.

Why is media corruption such an enduring problem in China?

The practice of news extortion, and all other forms of media corruption, is quietly and insistently reinforced by the calculus at the heart of state-led journalism. As a matter of Party practice and doctrine, media in China are not agents of transparency and accountability, with their own reserves of hard-earned credibility, but rather servants of the ruling Party’s truth. This means facts and revelations must constantly be buried in the push to “emphasize positive news” and “tell China’s story well.”

When media serve power rather than hold it to account, it stands to reason that they are vulnerable to the same distortions and excesses as unaccountable power.

Read some of the incredible cases, and delve into why news extortion remains such a persistent problem in China, in “China Fake Press Problem” by CMP Director David Bandurski.