Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 19 December

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

Firstly, and most importantly, the China Media Project team would like to wish all of our subscribers a very merry Christmas and a happy New Year! Thank you all for your support — be it through joining our paid subscription program or simply by reading and sharing our work. It’s easy to forget this newsletter is barely one year old, and that we’ve managed to go from zero subscribers to thousands in that time thanks to readers like you. If you’d like to upgrade to a paid subscription, we’re offering a 20 percent discount until December 31.

We’ll be taking a break over the holidays but will be back again in January 2025. Today’s newsletter is, as ever, a mix of the latest stories from Chinese-language media in the PRC, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and beyond. Before we get stuck in, though, we also wanted to note another recent development in the space.

In Malaysia, the political opposition is sounding the alarm over a recently passed Online Safety Bill that they say could drag the country into a “digital dictatorship.” Authorities insist that reforms will make it easier to arrest cyber criminals, but press freedom advocates say relevant laws have been used by the authorities in the past to harass their critics. Now, the country’s communications commission will have unfettered power to decide what content should be taken down and to compel service providers to provide user data. For more on the background behind this latest development, revisit our interview with Malaysian media scholar Benjamin YH Loh.

Enjoy and see you again in the new year!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

Moral Models

On most days, the Chinese Communist Party’s official People’s Daily newspaper is a slim 20 pages — with around 16 of those pages dedicated to tinder-dry accounts of official Party business, focusing on the inspirational (they said it, not us) leadership of Xi Jinping. But on Monday this week, the paper was a fat 32 pages, thanks to 27 pages announcing Chinese across the country who have been designated as candidates for national “moral models” (道德模范).

What are “moral models” and what purpose do they serve?

Held every other year since 2007, the National Moral Model (全国道德模范) process is overseen by the Central Propaganda Department together with its Central Civilization Office (中央文明办). Its goal since the Hu Jintao era has been to emphasize the notion of “spiritual civilization” (精神文明), which is about promoting ideals, morals, and ethics that ultimately serve the Party and its project of “socialist modernization.” At its core is the conviction that the Party itself must remain the essential and legitimate moral heart of Chinese society.

Nominees for “moral model” status are generally seen to exemplify the spirit of self-sacrifice and contribution toward the cause of socialism. Based on our quick study of candidates across the country, however, there is a clear gender gap in those selected for the CCP honor.

BUZZWORDS

Fingertip Patriots

Two pieces in the Hong Kong press point to soul-searching in the pro-Beijing camp

An unusually fiery op-ed by pro-Beijing political commentator Chris Wat Wing Yin (屈穎妍), published this week in Speak Out HK (港人講地), argues that more than four years of “patriots-only” governance has put Hong Kong in the hands of craven, incompetent politicians intent on "copying the old paths that others are no longer following" and "abandoning [Hong Kong's] strengths to embrace the outdated shortcomings of the mainland." This line of argument would not be a surprise from an exiled, pro-democracy media outlet — but it is unusual to see it coming from inside the house.

Speak Out is a digital media outlet founded and run by close allies of former Hong Kong chief executive Leung Chun-ying (梁振英). The least-trusted news source in the city, it is known for aggressively defending the Chinese Communist Party in general and Leung’s interests in particular (more in our special LS investigation).

The piece’s author has a colorful past. A rarity among pro-establishment voices, she got her start in the Next Media empire of jailed media tycoon Jimmy Lai. She has also worked with the more liberal Ming Pao (明報). Her CV — including an arrest in the mainland on national security grounds in the 1990s — has even inspired some conspiracy theorists to call her Lai’s sleeper agent in the pro-Beijing camp.

This is far from the first time we've heard a pro-Beijing voice criticize their own side for being all talk and no action. But it is noteworthy that Wat associates the city’s ailments with a kind of mainlandization — an accusation historically leveled by opposition politicians, most of whom are now behind bars. These bad old ways, Wat says, include Moutai-fueled banquets, judging politician performance by who shows up to the most patriotic events (even if they fall asleep or play on their phones), and "fingertip formalism" (指尖上的形式主義) — a new term for officials who perform all the right rituals yet get nothing done.

By accusing incompetent patriots of turning Hong Kong into what the mainland used to be, she is also providing a critical caveat — the city shouldn’t become like the China of the 1990s or 2000s, but it should become more like the China of today. She is still a loyalist, after all.

So Close Yet So Far

A second example of a surprisingly critical op-ed by a member of Hong Kong’s pro-Beijing commentariat came this week in a piece for HK01 by Yeung Chee Kong (楊志剛), a former associate vice-president at Hong Kong Baptist University. Yeung wrote that One Country, Two Systems (一國兩制) — Deng Xiaoping’s formulation to guarantee Hong Kong’s autonomy after its 1997 handover to the PRC — has failed, dashing hopes for “reunification” with Taiwan.

"The original intention of One Country, Two Systems,” Yeung wrote, “was the peaceful reunification of Taiwan. If Hong Kong led by example in creating a happy home [with China] it would be a role model for Taiwan compatriots to envy and admire, and peaceful reunification would become [Taiwanese] people's wish... but we have become a negative example instead."

Admitting that One Country, Two Systems has failed in Hong Kong is a bold stance — at least within the “patriotic” camp. Many observers and academics readily point to how Beijing’s crackdown on Hong Kong has made the idea lose all appeal to Taiwanese, leading even the country’s China-friendly to openly swear off any kind of similar arrangement.

The columns by Wat and Yeung demonstrate how even Hong Kong’s most patriotic media are finding ways to criticize the system of “patriots ruling Hong Kong” (愛國者治港) as it becomes clearer that loyalty to the CCP is not the most reliable yardstick for political effectiveness. Still, they must rein their horses in at the cliff’s edge, redirecting criticism away from Beijing — lest they fall victim to the very crackdown they have thus far cheered on.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Shamed Into Silence

Human rights defenders run a range of risks — from threats to their families to attempts by their home governments to monitor and intimidate them overseas. For women in the field, these threats can be even more numerous, and serious. A new study by the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab finds that exiled and diaspora women who are human rights defenders face gender-specific forms of online harassment, abuse, and intimidation on top of the same digital threats facing their male colleagues.

Lingua Sinica spoke with three of the report’s authors to learn more. Stay tuned for the full version of our interview in a special edition of Dalia Parete’s “Intersections” bulletin tomorrow. A short preview is below:

Lingua Sinica: China isn’t the only country engaging in these tactics, but is there anything in its behavior that sets the PRC apart from other repressive regimes?

Marcus Michaelsen: China’s campaign of transnational repression is remarkable for its global scale and persistence. The Chinese government relies on methods like coordinated online harassment and defamation campaigns to intimidate human rights defenders and journalists abroad across the globe. In the cases of the Uyghur human rights advocates we interviewed, a widely used method was video or audio calls from the homes of their relatives in Xinjiang by local authorities. These calls were meant to threaten activists abroad so that they could stop their public advocacy. At the same time, China also leverages its consulates and the large diaspora for threats against activists abroad. Respondents told us that they were being followed and harassed in public, either by agents likely affiliated with the embassy or by loyalists among the Chinese overseas populations. One respondent told us that a lecture she gave at a university in the US was repeatedly disturbed by a Chinese student in the audience.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

AI Filial Piety

At a Politburo study session in October, Xi Jinping stressed the need for China to safeguard its traditional culture by merging it with both Marxism and the latest technological developments.

Beijing’s Municipal Government and the video streaming app Kuaishou seem to have gotten the message. They recently unveiled a series of nine “short films” (短片) on the platform, each directed by a renowned Chinese filmmaker and created with Kuaishou’s “Kling AI” (可灵AI) video generator. Behind one was Jia Zhangke (贾樟柯), the darling of China’s once-edgy “Sixth Generation” of filmmakers, known for his gritty depictions of China’s urban underworld.

Jia explained in one interview that his short film blends old and new, using “very traditional film narrative methods, and then there are robots in it.” What we get is “Wheat Harvest” (麦收), the story of a robot that goes down to the Shanxi countryside to help his owner's parents gather in the harvest. Along the way, the robot performs other virtuous deeds like helping an old man cross the road and visiting various cultural sites. At the journey’s end, its owner’s elderly mother nuzzles the robot fondly, noting it even speaks their local dialect flawlessly — something her own progeny, due to the enforcement of Mandarin at the expense of regional languages, is likely unable to do. The picture fades on Jia’s robot, contently scything corn in the golden glow of a socialist sunset.

What “Wheat Harvest” depicts, most of all, is China's vision for AI: not as a catalyst for social disruption but as a tool to perfectly harmonize Communist Party orthodoxy with traditional Chinese cultural values. It’s also an apt reminder of the trajectory of many Chinese auteurs whose success in their art form brings them to the attention — and, inevitably, the service — of the CCP. Like Zhang Yimou or Chen Kaige, Jia’s only choice was to retire early enough to remain an internationally respected filmmaker or work long enough to become a propagandist.

STORYTELLERS

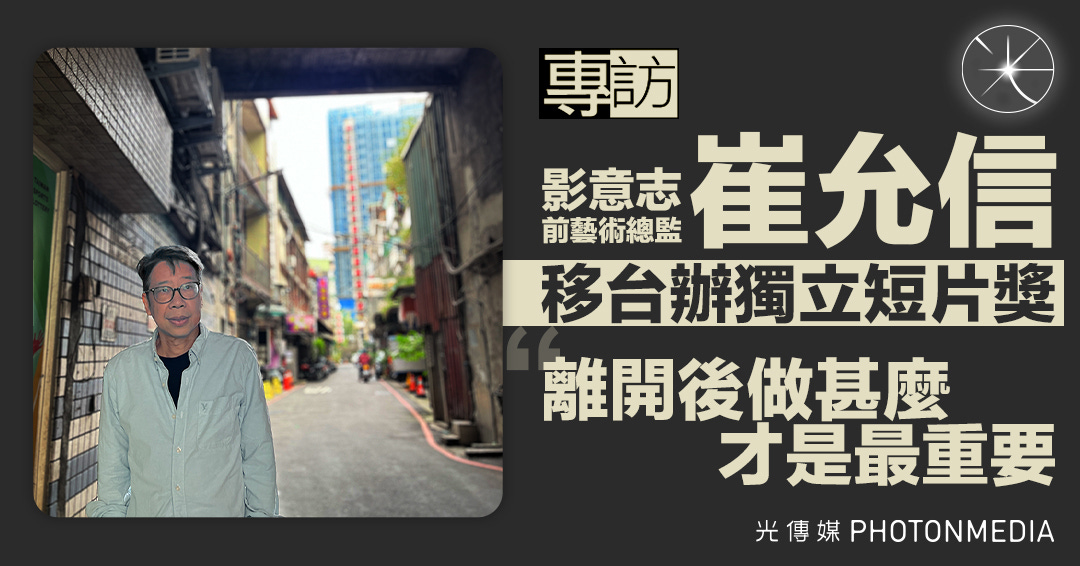

Vincent Tsui

A Hong Kong filmmaker stumbles into a new life in Taiwan

This week the exile Hong Kong media outlet Photon Media profiled Vincent Tsui (崔允信), a Hong Kong filmmaker who has now lived in Taiwan for three months — having left the beloved city that has been his home for a half century. How has the transition to life in Taiwan gone for the independent director, who first entered the public eye with his 1997 documentary film "As Time Goes By" (去日苦多), co-directed with acclaimed Hong Kong New Wave filmmaker Ann Hui (許鞍華)? "For 50 years he has lived and worked in one place," the story begins. "To leave so suddenly a place to which you've grown so accustomed, he laughs, inevitably means stumbling over certain things."

Also in 1997, Tsui founded Ying e Chi (影意志), or “HK Indie” a group of independent filmmakers that over the following two decades released a number of independent films and documentaries, flourishing in the free and open creative space offered by Hong Kong. Tsui had a premonition in 2020 that the implementation of the national security law would encroach on that space, and he was not wrong. In 2021, the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (HKADC), for years a staunch supporter, withdrew its funding from Ying e Chi. Shortly after, Tsui was interviewed about this story by Stand News (立場新聞), one of the city’s last remaining independent news outlets. It wasn’t long before the offices of Stand News were raided by police, and senior staff arrested — signaling the further escalation of political repression in the city.

In October this year, shortly after his arrival in Taiwan, Tsui started up the Facebook page "HK Indie Ying E Chi (影意志Ying E Chi), planning a fresh beginning for the film collective he formally closed, very quietly, last year. Tsui has since announced plans for a new round of HK Indie Film Awards in Taiwan for 2025 — and he has already received scores of entries.

"I left for freedom,” he told Photon Media, “but what to do now that I’ve left is the most important thing."

IN THE NEWS

Taken In or Taken Away?

This month, the case of Bu Xiaohua (卜小花) has rattled the Chinese internet. The 45-year-old woman was found in a rundown farmhouse in Shanxi province at the end of November — 13 years after she disappeared from her family home over 100 kilometers away.

When she went missing in 2010, Bu was a promising master's degree graduate in mechanical engineering with plans to pursue a PhD — a young woman with an apparently bright future. Why she disappeared when she did, only to turn up over a decade later in the home of a stranger presented a mystery, and one which only deepened considering the state she was found in: malnourished, confused, and with a hazy memory of her own past. The way her story was portrayed by official channels only raised more questions and concerns. An official release described her as having “gone missing from home” (從家中走失) and being “taken in” or “sheltered” (收留) by the man who would father two children with her, Zhang Ruijun (张瑞军).

Many Chinese have asked: Shouldn’t we instead be treating this as a case of “kidnapping,” “trafficking” and possibly rape?

Such accusations have been vehemently denied by Zhang and his family, who say that Bu was unemployed, schizophrenic, and “useless to the nation” (對國家無用的人) when Zhang took her in as an act of charity, “feeding, clothing, and taking care of her” for over a decade.

But even if the truth lies somewhere between “kidnapping” and “sheltering,” the story raises serious questions about how the mentally ill are treated in Chinese society. Although Bu’s family sought help from the police when she first disappeared, she was allowed to slip through the cracks. For many, the case has troubling echoes of the infamous “chained woman” of Xuzhou case in 2022 — when a victim of human trafficking was discovered in rural Jiangsu, kept like a prisoner in a backyard shed by her captor, also referred to in media reports as her “husband.”

Like the “chained woman,” Bu Xiaohua’s case was only resolved after the story went viral on social media, compelling local authorities to find Bu and reunite her with her family in her home village. In an essay that has already been scrubbed from the Chinese internet, one WeChat user suggested that “if it weren’t for the online exposure, nothing would’ve happened.”

NEWSMAKERS

An independent news outlet that wants to “Leave no one behind”

Founded back in 2019, Right Plus (多多益善) identifies itself as the only independent media outlet in Taiwan dedicated to public service reporting. The site, which is funded by small donations from the public as well as corporate sponsorships and cross-disciplinary partnerships (跨領域合作), says its goal is to "fill a gap in journalism in Taiwan, and a vacancy in the area of in-depth public interest reporting."

Right Plus is administered by the non-profit Taiwan Citizen's Dialogue Association (社團法人臺灣公民對話協會), which upholds Principle Two of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals: “Leave no one behind” (不拋下任何人). The Chinese name of the outlet (duō duō yì shàn) derives from an idiom that first appeared in the Han dynasty Records of the Great Historian (史記), and means “the more the better.”

Among the pieces posted by the outlet this month is a reflection by social worker Kuo Ko-Pan (郭可盼) on how to communicate with individuals with schizophrenia. Like nearly all of the posts at Right Plus, it includes a “Key Summary” (重點摘要) right at the top — delivering important takeaways.

GOING GLOBAL

Walking It In

In Myanmar’s repressive press environment, China is finding a foothold

Operating in Myanmar, under the ruling military junta that seized power in 2021, means foreign media have to abide by strict reporting restrictions. It’s an onerous set of conditions that few international news sources besides China’s are willing to accept, leaving PRC outlets some of the only members of the foreign press corps officially accredited by the country’s Ministry of Information.

This special relationship was deepened earlier this month when the state-owned China Media Group (中央广播电视总台) unveiled its new series China Walk (漫步中国). A co-production between CMG and the official Myanmar Radio and Television (MRTV), the show is due to air on all of the country’s major TV networks. Billed as an opportunity for “people of both countries to learn about the cultures and customs and have a better understanding of each other,” China Walk takes viewers to tea villages in Yunnan and tropical Hainan island — but it isn’t just about culture and soft power. China Walk is also expressly intended to promote the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Xi Jinping’s signature, globe-spanning infrastructure development strategy.

The political stakes involved in this otherwise innocuous-sounding TV series were underscored at the launch ceremony organized by CMG and MRTV in Yangon. Myanmar’s Deputy Minister for Information took to the stage, predicting that “people-to-people relations will be improved” thanks to the show. The Minister Counselor of the Chinese Embassy in Myanmar also delivered remarks, emphasizing the importance of media cooperation in building a “global civilization” (全球文明). Separating culture from politics is never easy — but in this case, no attempt was made.