Lingua Sinica Newsletter, 13 June

News, analysis, and commentary on Chinese-language media from the PRC and beyond.

Welcome back to Lingua Sinica.

A belated happy Dragon Boat Festival to all who celebrated (and hopefully got a day off) over the past weekend. The festivities left us with less time than usual at our desks this week but we trust there’s still something for everyone in this round of the Lingua Sinica newsletter: from the latest on China’s international communication centers (ICCs) to state media talking points in Hong Kong and a Twitter spat over warming India-Taiwan ties.

Before getting into it, though, we want to remind readers again about the paid subscription plans we plan on launching at the end of the month. As some of you may know from our last Lingua Sinica newsletter, this will remain free. But for paid subscribers, we have great new benefits on the way — and the opportunity to support the unique work of the China Media Project team.

Because we appreciate the support that everyone who signed up for free has been giving us since day one, however, we won’t be taking away any of the content that you signed on to receive. Free subscribers will continue to get our biweekly newsletter in full plus new one-off posts as they go out. Our paid membership options will be there for those among you who want to dig that bit deeper and/or show that you appreciate us, too. These will go live on July 1.

Look out for a standalone post on Lingua Sinica tomorrow from CMP Executive Director David Bandurski that will lay everything out in even greater detail. Until then, happy reading!

Ryan Ho Kilpatrick

CMP Managing Editor

REDLINES

Forever Developing

In a video address Wednesday to the 60th anniversary of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), Xi Jinping stressed the importance of “south-south cooperation” (南南合作) — meaning the building of close trade relations between developing countries. Xi also took the opportunity to promote China’s leadership role among developing nations, a counterpoint to the G7 summit happening in Italy this week.

China's continued classification as a developing nation at the UN, which affords it a range of preferential benefits designed to minimize the financial burdens of lower-income members, has been a bone of contention in recent years. As Wilson Center president Mark A. Green argued in a blog post one year ago, this status does not gibe with its growing economic clout, expanding nuclear arsenal, and substantial space program. “Is China ready to recognize that if it wants the world’s respect as a great power, it cannot also ask for its pity as a developing nation?” Green asked.

In his video address, Xi elaborated on his emphatic statement last year that China was not just a developing country still, but that it would be a developing country indefinitely. “China has always been a member of the ‘Global South,’” he said, “and it will forever belong to the ranks of developing nations.”

What does Xi Jinping mean by “forever”? Read our breakdown at CMP. Hint: it’s about claiming political leadership over the “global south” to balance against the developed West.

BUZZWORDS

Two Systems With Chinese Characteristics

Five years since police and pro-Beijing voices railed against “cockroaches” in Hong Kong — their word for pro-democracy protesters — a new “roach” has piqued their ire: American economist Stephen Roach.

The former Morgan Stanley Asia chairman and Yale lecturer was already infamous within pro-establishment circles for his proclamation that “Hong Kong is over” as a result of the erosion of its autonomy and civic liberties since the government’s national security crackdown began in 2020. State-owned media outlets have even ascribed a word to this belief, in order to better denounce it: “Hong-Kong-is-over-ism” (香港玩完論). And with Roach back in Hong Kong recently, reiterating his stance in a speech to the city’s Foreign Correspondents’ Club, columnists have lined up to take a shot at Roach.

The Communist Party-linked Ta Kung Pao (大公報) newspaper ran an op-ed by Tu Haiming (屠海鳴) on June 6 railing against "Hong-Kong-is-over-ism." Tu, who leads the Chinese General Chamber of Commerce, says that Roach dubbed the present reality in Hong Kong "Two Systems with Chinese Characteristics" (中國特色的兩制) — something that Roach meant as a jab, but which Tu takes as a badge of honor: "What's wrong with Two Systems with Chinese Characteristics?" he asks.

Did he say that, though?

The phrase, or variants of it, has been used in critical contexts before in English. But searching for "Two Systems with Chinese Characteristics" in Chinese turns up virtually nothing before Tu's op-ed. The transcript of Roach’s FCC speech, which Roach posted to his Substack, does not contain the phrase, and nor do earlier press interviews with Roach. So was Tu just making something up to get mad about?

Another Ta Kung Pao article, carrying remarks by NPC delegate Tam Yiu-Chung takes an oddly similar line, accusing Roach of “smearing One County, Two Systems” without providing examples of him doing this. This synchronicity, however, could point to a shared line: that government critics are undermining the political framework that has been foundational to Hong Kong’s success in the post-handover, pre-national security law era — when, in reality, critics of the ongoing crackdown are probably more interested in defending the One Country, Two Systems of that time.

CHAIN REACTIONS

A Deep Dive into Deep China

This new information brand that claims to be “an elite academic initiative” is a cloaked Chinese state media product.

Last week, a reader wrote to Lingua Sinica about a media account that had been sending them unsolicited e-mails with positive reports about China, including a mini-documentary called “Cotton Field Life” that portrayed the peace and prosperity of Xinjiang, where the United Nations has found credible evidence of torture and other systematic human rights abuses against the Uyghur Muslim population. DeepChina advertises itself as “an elite academic initiative that offers objective and rational analyses on a broad spectrum of topics related to China.” Our reader noted that the initiative “seems to be a Chinese propaganda outlet.”

We took a deeper look to find out who exactly is behind this media brand.

Launched just one year ago, DeepChina now operates an array of social media accounts overseas. So far, it has had little traction except on Facebook, where it has more than 700,000 followers. Many of DeepChina’s socials point to its Substack publication, which appears to be the focus of its overseas presence. However, much of the content on the publication is cross-posted on its website (Substack and here, for example), a subdomain at China.org.cn, China’s authorized government portal site under the State Council.

While China.org.cn is one of the Chinese government’s key outward-facing web portals, its production is overseen by the China International Communications Group (CICG), the same state-run media conglomerate that publishes such CCP external propaganda stalwarts as the Beijing Review and China Today.

DeepChina is a prime example of the phenomenon of “cloaking,” by which state media outlets disguise their hand in media products overseas. In recent years, particularly since Xi Jinping’s speech on external propaganda on May 31, 2021, China has accelerated the creation of such branded accounts on foreign platforms, often through regional-level International Communication Centers (国际传播中心).

But there is one more dirty little secret behind DeepChina. Our reverse image search of its logo quickly tracked down an identical design for the Berlin-based Czars Design Studio. Oof. Shallow move, DeepChina.

NEWSMAKERS

A Skylight Opens in Hong Kong

When censorship opens a void, the journalist’s last act of defiance is to make that void speak.

On June 2, just ahead of the 35th anniversary of the Tiananmen Massacre, Hong Kong’s Christian Times (時代論壇) newspaper published its latest edition with a strange blanks on the first and second pages.

These voids marked the space where the paper had originally intended content on the events of June 4, 1989 — including an editorial noting how the events of "spring and summer of that year" were an important part of the collective memory of a generation of Hong Kong people. A note on the publication’s website said simply that “the front-page feature could not be published,” but it was clear from this act of protest that it was related to restrictions in Hong Kong under new national security legislation introduced earlier this year, known as Article 23. As InMediaHK (獨立媒體) reported, this was a classic case of “opening a skylight” (開天窗).

The phrase “opening a skylight” refers to the occasional practice in Chinese print media of leaving empty spaces on the news page in cases where content has been pulled under censorship orders. A form of silent protest by journalists and editors working in repressive environments, the blank space signals to the reader that content has been removed.

In China, this practice goes back to the beginnings of the mass newspaper in the late Qing era (1644-1912), and one famous instance appears right around the revolution that ended the dynasty. On October 11, 1911, news of the armed rebellion known as the Wuchang Uprising (武昌起義), which marked the start of the Xinhai Revolution (辛亥革命), was forcibly removed by the Qing police from the National Spirit Daily (國風日報). The following day, a full-page “skylight” appeared on the front page of the newspaper, with a single line: “This newspaper has received a lot of news about Wuchang, but due to police interference, all of them have been cut off, and those who read them are forgiven.”

In the immediate aftermath of a deadly high-speed train collision in Wenzhou on July 23, 2011, China’s leadership moved to contain the crisis by restricting media coverage and commentary. Furious at the cover-up, which was made ridiculous by the real-time sharing of footage on social media, journalists at some newspapers protested by opening skylights on their commentary pages. On July 30, the China Business News (华商报), a commercial paper published by the Shaanxi Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese, ran a “skylight” on page B2, directly under a commentary that called vehemently for a full investigation to restore public trust.

But opening skylights is not just a phenomenon in Chinese-language media. As Taiwan’s Watchinese (看雜誌) magazine has documented, there have been many instances of the practice in newspapers around the world, including the Washington Post.

GOING GLOBAL

Tianjin and Zhejiang Get ICC’d

The CCP is going local with global propaganda.

On June 7, the municipality of Tianjin became the latest provincial-level jurisdiction in China to launch a central office for disseminating foreign propaganda. According to coverage in Tianjin’s flagship CCP-run newspaper, the Tianjin Daily, the center will focus on television, radio and multimedia products for foreign distribution, as well as “major international events,” all to “present a true, multidimensional, and lively image of Tianjin.”

The formation of the Tianjin ICC follows closely on the heels of the set up on May 31 of Zhejiang International Communication Center (浙江国际传播中心), or ZICC. A release from provincial media in Zhejiang called ZICC “an all-in-one communication platform.” The center consolidates state media resources at the provincial level. It comprises websites, dedicated news channels, and an “overseas social media platform account matrix” with a total follower base of over 8 million.

With the addition of the Tianjin and Zhejiang centers, the number of provincial-level ICCs in China now stands at 27.

China’s provincial and city-level international communication centers, or ICCs, are spearheading efforts promoted by the leadership since 2018, and accelerating over the past two years, to “innovate” foreign-directed propaganda under a new province-focused strategy. In June 2023, provincial and city-level ICCs in China created a mutual association to better coordinate work nationwide. Integrating the ICCs horizontally and vertically, including with central state media, has begun to emerge as a core strategy in the CCP’s remaking of its overall propaganda matrix.

SPOTLIGHT

Five Years

Five years have passed since protests against a proposed extradition bill in Hong Kong morphed into an unprecedented, city-wide movement demanding democracy — and precipitated an unrelenting government crackdown that continues to this day. For those of us who participated in and reported on those protests, it’s hard to believe that a full half a decade has gone by since Hongkongers marched in their millions and were ignored, then silenced.

The anniversaries of the biggest protests on June 9 and 12 have been an occasion for a number of media outlets and NGOs to mark the occasion with new reports. One, though, truly stands out. An in-depth report from the independent Taiwanese news outlet The Reporter (報導著), “The 5th Anniversary of the Anti-Extradition Bill Movement: Hong Kong's Changes and Trends in Demography, Economy, and Culture,” does exactly what it says — it “lets the numbers speak” for themselves.

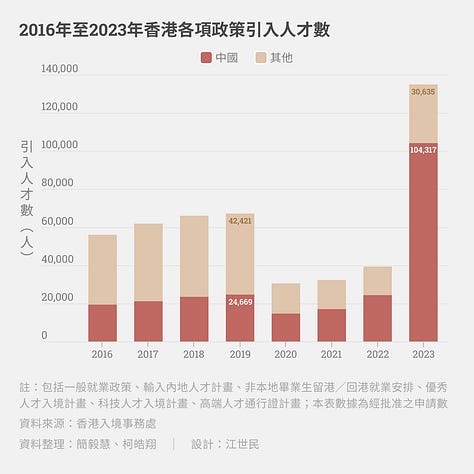

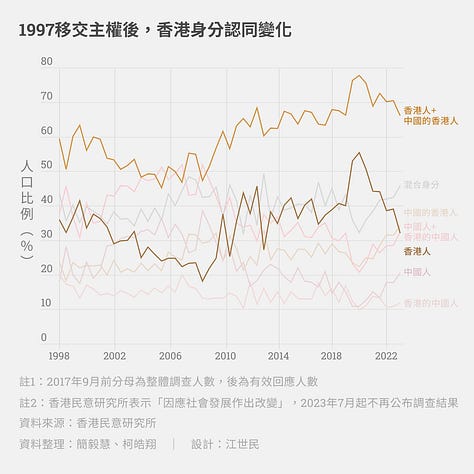

Some of the many illuminating graphs you’ll find in this piece include Hong Kong’s slipping trade figures; where Hongkongers have been moving to in what numbers; the overwhelming proportion of overseas talents and companies coming to the city from mainland city as opposed to the rest of the world; and how surveys on local identity have fluctuated since the 1997 handover. It’s a treasure trove for anyone interested in Hong Kong and for fellow reporters especially. Every one of these graphs hints at a fascinating story that can be told in myriad other ways.

QUOTE/UNQUOTE

Seeking Truth in Unlikely Places

China Central Television, or CCTV (央視), is often likened to “the BBC of China.” But the comparison is a very imperfect one. While both take public funding, one has its editorial independence guaranteed by a royal charter, while the other is a mouthpiece (the leadership’s own term) for the ruling Communist Party. Day to day, both are motivated by different answers to the question of what journalism ought to be: is it holding power to account, or serving power?

To learn more about what sets these two worlds apart, where they’re drawing closer, and where they’re drifting further apart, Lingua Sinica spoke with Vivien Marsh, a former BBC journalist with decades of experience whose recent book Seeking Truth in International TV News is an in-depth comparison of how and what the BBC and CCTV — now rebranded as CGTN — tell their respective audiences.

Lingua Sinica: You write about how the way CCTV-News and CGTN news are organized and presented is totally different from what Western viewers would expect of the news. Can you give some examples of this?

Vivien Marsh: It comes down to the different conceptions of the role of journalism in Western and particularly Anglo-American societies when compared with the Chinese state. It’s the difference between holding elected (and other) power to account, and acting as an arm of the state or — if viewed more charitably — an interface between the leadership and the people.

LS: How successful has CCTV’s international arm, CGTN, been in imitating what you call the “televisual grammar of the West?”

VM: This is one area in which CGTN has made great strides. The product looks much slicker than did that of CCTV-News when I first started studying China’s anglophone television in 2013. Ways of storytelling that are familiar to Western viewers, such as the choice of strong pictures or the foregrounding of the reporter with a walk-and-talk or piece to camera, gradually found their way into China’s English-language TV news output.

For a journalistic culture that regards reporters as the lowest element of the food chain, the editorial elevation of the individual has been a significant change. But as one of CCTV’s journalists told me during my research, the objective was to “learn from the West [and] use their way to report stories so [Western viewers] accept China’s image.” Many of my Chinese interviewees from CCTV-News and CGTN talked of their aspirations to journalistic professionalism. This appeared to refer to clarity and technically proficient presentation rather than editorial attributes such as due impartiality or balance.

LS: In Taiwan, we’ve noticed a trend in PRC propaganda away from positive stories about China — which are regarded with a high degree of suspicion — and toward stories undermining confidence in Taiwan’s democracy and its allies, particularly the United States. Have you noticed this elsewhere as well?

VM: This has been a feature of CGTN’s news output in recent years, particularly, as you say, with regard to the United States. I analyzed a cross-section of CGTN news output in 2023 and found a preponderance of news items on US shootings, US police violence, and perceived US economic instability. The treatment of these stories was journalistically even-handed although the topics themselves appeared to have been selected for the negative light in which they showed the United States.

For our full interview with Marsh, stay tuned to the CMP website.

ANTI-SOCIAL LIST

Tweeting Up a Storm

On June 5, just one day after he was officially re-elected as prime minister of India, Narendra Modi tweeted himself right into the choppy waters surrounding the Taiwan issue. Taiwan president Lai Ching-te, who assumed office last month, had congratulated Modi on his win, and the Indian leader responded with thanks and hopes for “closer ties” between the two countries — an innocuous, even anodyne expression between most world leaders, but not when it comes to China and its claims over Taiwan.

Needless to say, the PRC was not about to “like” that tweet. The following day, Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning (毛宁) responded to a question on the exchange, rehashing the usual boilerplate about the One China Principle and stern opposition to “official exchanges in any form” with Taiwan.

The Global Times, an outlet under the CCP’s flagship People’s Daily, reported on Mao’s staid remarks while adding some of its own trademark fiery rhetoric. The newspaper had plenty of accusations to go around: Lai was “going along for the ride” when he tweeted at Modi; Taiwan “engages in political plots”; Modi is betraying India’s national interest by leading it down a path of getting “closer to America and more distant from China,” while Washington seeks to turn his country into a “bulwark against China.”

Just before Modi’s contentious tweet, the state-run China Daily was keen to strike a more magnanimous tone. Writing in English for an audience that presumably includes Indian readers, the paper said it was time for New Delhi to stop fanning the flames of “jingoism” and “not be drawn into Washington's geopolitical game” just because of a few niggly border skirmishes with China’s armed forces.

FLASHPOINTS

Testing the Limits

It’s a scene familiar to all Chinese who watch the news coverage of the country’s national college entrance examinations each year. Pouring out of the testing hall, high school students are greeted by parents anxious to know how it went. But as students emerged last weekend, following the nation’s biggest “gaokao” (高考) ever, there were rare public expressions of political activism. Unfolding in various places in the country, these were not protests (of course) against China’s government. Rather, they spoke openly against Israeli actions in Gaza.

In several protests documented online, students could be seen waving Palestinian flags and chanting pro-Palestinian slogans after dashing out of their exams. In one case logged by a popular X account, a student rushing out of the exam hall at Changjun High School (长郡中学) in central China’s Hunan province grabbed a reporter's microphone and emotionally expressed his desire for world peace, citing the ongoing war in Palestine. “In another place, Palestine, there are children smaller than me whose home, whose homeland is in the midst of war,” he said after thanking his parents and his school. “I wish for peace in the world!”

SOURCE CODE

Nair-y an Unkind Word

Page three of the June 1, 2024 edition of the Chinese Communist Party’s official People’s Daily included a commentary attributed to Chandran Nair (钱德兰·奈尔), the founder and CEO of Global Institute for Tomorrow (GIFT). Nair, a Malaysian businessman and scholar, has been a frequent critic of what he deems to be the "outrageous narrative" and “mass hysteria” of Western media on China, and he has often been cited and interviewed by Chinese state media in praise of the country’s record in areas such as poverty alleviation and economic development.

Nair’s People’s Daily piece, which calls on the United States to have “a correct view of China’s development” (正确看待中国发展) as a peace-loving nation contributing to global well-being, praises Xi Jinping’s signature international programs. At points Nair’s piece parrots verbatim the official discourse of the CCP. His line that “China is committed to promoting the building of a community of shared destiny for mankind” might have been pulled directly from Xi Jinping’s political report to the 20th CCP Congress in October 2022. In the next breath, he refers to Xi Jinping’s international strategies, including the Global Civilization Initiative (GCI), as “international public goods” (国际公共产品).

Never mind that China’s leadership defines concepts like “democracy” and “freedom” under the GCI in ways that depart dramatically from any recognizable form seen in free and even less-free societies. First raised by Xi Jinping in 2019, the notion of “whole-process democracy” (全过程民主), or quanguocheng minzhu, is the bald assertion that China’s one-party state is more participatory than democratic systems in the West. Traveling along a rhetorical Moebius strip, the CCP leadership argues that “whole-process democracy” means ensuring that “the people are in charge” (人民当家作主); and ensuring the people are in charge is grounded fundamentally in “adhering to the leadership of the Party”(最根本的是坚持党的领导).

Say what?

As a commentary in the PLA Daily clarified this understanding of “democracy” in March, echoing Xi: “East, south, north and center, Party, government, military, society and education – the Party rules all. The leadership of the Chinese Communist Party is the fundamental political guarantee for the implementation of whole-process democracy.”

CMP IN THE HEADLINES

Hey Chatbot, Leave Those Kids Alone

In a recent cover story called “Teacher’s Pet,” The Wire China takes a close look at how China’s leading AI companies, including iFlytek — which CMP has covered here and here — are responding to the demand gap created when the government cracked down on education services in July 2021. “In the three years since,” the authors write, “Beijing has made clear it intends to be the global leader in implementing AI into its massive education system.”

The story draws on the insights of CMP’s on-staff AI expert, Alex Colville, who explains:

“The Party-state wants to harness AI in the same way it did the Internet in the late 1990s. If the leadership can tame AI, this might further empower their push for social and political stability in the 21st century.”

For essential CMP coverage of AI trends in China, we recommend:

"Sparking Compliant AI" — a deep dive into how China is trying to make its industry-leading chatbots speak like the Communist Party

"Talking Tiananmen with a Chinese Chatbot" — a halting dialogue with China's top chatbots to see what, if anything, they have to say about the past.