Keeping the Memory of June Fourth Alive

On the 35th anniversary of the massacre of students and other demonstrators on the streets of Beijing on June 4th, 1989, remembrance remains an act of defiance.

Today marks the 35th anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre in China, when pro-democracy protests and demonstrations that had simmered for months following the death of the former pro-reform CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦) culminated in the brutal murder of hundreds, and perhaps thousands, by the soldiers of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

To quote one Chinese writer on June Fourth, paraphrasing British novelist Julian Barnes: “With time memory becomes indistinct” (時間令記憶變得不確定). But for many, still, the memories of what happened near Beijing’s Tiananmen Square in the early hours of June 4, 1989, remain painfully distinct and defining — inspiring, however quietly, action and aspirations for the future. Here are the words of demonstrator and later rights defense lawyer Pu Zhiqiang (浦志強) as he lucidly recalled the night on the occasion of the 17th anniversary of the massacre:

I recall the early hours of June 4, 1989. The few thousand students and other citizens who refused to disperse remained huddled at the north face of the Martyrs’ Monument in Tiananmen Square. The glare of fires leaped skyward and gunfire crackled. The pine hedges that lined the square had been set ablaze while loudspeakers screeched their mordant warnings.

To mark this day, and to underscore its crucial relevance for media and speech freedoms in China, we offer Lingua Sinica readers two evergreen pieces from our China Media Project archives.

The first, “The Telegram,” is a wonderful reflection from former CMP director and veteran journalist Qian Gang (錢鋼) in which he shares his experiences as pro-democracy demonstrations gripped China in the spring of 1989 — and the consequences of his support for a newspaper editor at the center of events that year. At the time, Qian Gang had already achieved national acclaim as a writer of reportage with this book The Great Tangshan Earthquake (唐山大地震).

The second, “How a Massacre Shaped China’s Media,” takes a closer look at the role calls for greater media freedoms had in the protest movement that gripped China in 1989, and how the press and public opinion controls introduced by the CCP in the aftermath of the crackdown still reverberate today for all Chinese citizens.

On the June 4th spirit and its relevance to Hong Kong, we also recommend readers revisit our interview last year with Mak Yin-ting, a Hong Kong journalist who reported on the June 4th massacre and went on to become a leading voice defending press freedom in her home city. For historical materials on June 4th, we encourage readers also to revisit the in-depth multimedia special created for the 25th anniversary 10 years ago by the South China Morning Post in cooperation with the Journalism & Media Studies Centre at the University of Hong Kong, with the involvement of the China Media Project. Such an unflinching exploration of the events of 1989, with direct participation by key eyewitnesses, would likely not be possible in Hong Kong today.

THE TELEGRAM

In April 1989, as protests raged in Beijing and other Chinese cities, I dispatched a telegram to Qin Benli (钦本立), the editor-in-chief of the World Economic Herald in which I expressed my sympathy and support following his ouster from the outspoken 1980s-era newspaper. I was an active-duty officer at the time, working as a reporter for the People’s Liberation Army Daily, where I was in charge of the news desk. Though intended only as a personal message of respect and support, that telegram opened a Pandora’s Box of troubles.

A Herald Fan at the PLA Daily

Back in those days, we were all in the habit of referring to the People’s Liberation Army Daily simply as the PLA Daily. We referred to the World Economic Herald simply the Herald. Nearly all of China’s newspapers in the 1980s were “organs” directly controlled by the Chinese Communist Party. The Herald, however, was different. The paper had been launched in 1980 by the Chinese Society of World Economics (CSWE) and the World Economics Research Center of the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences. It maintained its own independent financial accounting, and it was accountable for its profits or losses. This was all completely new.

My attention was first drawn to the Herald in 1985. At the time I had just taken charge of the news desk at the PLA Daily, and my post came with a subscription allowance for various newspapers and journals, the likes of the People’s Daily, China Youth Daily, Red Flag magazine and Xinhua News Agency’s China Comment.

When I read the Herald for the first time, the paper astonished me with its clear support for reforms, its daring declarations and its fresh ideas. The impression it made on me was so profound that I can remember many of the headlines to this day: “Political Reform is the Guarantee for Economic Reform”; “The Chinese Communist Party Needs Democracy Like it Needs Air”; “Separation of Party and Government is the Crux of Political Reform”; “We Cannot Afford Not to Study the Political Reform Thoughts of Deng Xiaoping.”

The PLA Daily was conservative by contrast. But in the 1980s, even our paper was raked with the howling winds of media reform. The broader trend in the media at the time was to clean away the poisons of the Cultural Revolution and the vagaries of what we called jia da kong (假大空) — the “false language,” “bluster” and “empty words” that had surfeited Party media throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

Plenty of people at our newspaper were more open in their thinking.

In 1979, the PLA Daily had re-republished a lyric poem from Poetry Journal called, “Generals, This Cannot Be Done,” which criticized the demolition of a nursery school to make room for apartments for high-ranking military brass. One of our deputy editors was transferred from the paper for giving publication of the poem the green light.

Among younger journalists like myself, support for reform was strong. We interacted quite a bit with journalists from China Youth Daily and other publications known to push the bounds. We had a particular taste for bolder content.

In 1987, the World Economic Herald sparked a nationwide debate over the question of China’s international standing and the need for reform. The paper argued that the gap was widening between China and the developed world — that unless China was more robust in its pursuit of reform and development, it would be left out of the race entirely. It concluded that “the most urgent matter before the Chinese people remains the question of its ‘place in the standings.'” The debate rumbled across China and even drew international attention. It had never been clearer that the Herald was driving the agenda.

My office would become a watering hole every time our copy of the Herald arrived at the PLA Daily. I distinctly recall one issue that discussed the issue of “shareholding,” something completely fresh to us at the time. We had a lively debate at the office about what our own enterprises might look like if workers and ordinary people held shares.

Only once did I come close to meeting Qin Benli face-to-face. That was in 1986, when two of our reporters at PLA Daily were assigned to ride bicycles along the coast, filing stories on the way. When they reached Shanghai, I joined one of the reporters on a visit to the offices of the World Economic Herald. The idea was to pay our respects.

My office would become a watering hole every time our copy of the Herald arrived at the PLA Daily.

Unfortunately, Qin Benli was not there that day. We met instead with one of the paper’s deputy editors. So in the end, I would only know Mr. Qin through the books of others, and of course through his work.

Revolutionary Newsmen

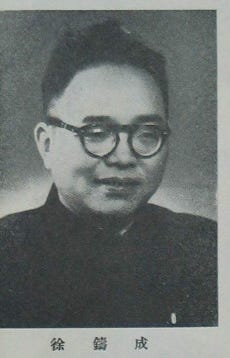

In the early 1980s, there was one book in particular that became a must-read for all of us working in the media. The book was News Anecdotes (报海旧闻), a memoir by former Wenhui Daily editor-in-chief Xu Zhucheng (徐铸成). During the Anti-Rightist Movement in 1957, there was a purge at the Wenhui Daily. Mao Zedong himself said that “the bourgeois-leaning tendencies of the Wenhui Daily must suffer criticism.” At the time of the purge, Xu Zhucheng was editor-in-chief and Qin Benli was deputy editor and secretary of the paper’s Party Leadership Group. While Xu was branded a rightist, Qin suffered only demotion.

Qin Benli was an old Party newspaper veteran. When the People’s Liberation Army took control of Shanghai in 1949, Qin and other noted Party journalists, including Ge Yang (戈扬), entered the city along with them. Qin Benli, it is said, even slept on the roadside with the soldiers at night. Qin Benli was tasked by the Party leadership with taking control of Shen Bao, China’s oldest modern newspaper. He also took part in the launch of the Liberation Daily, Shanghai’s official Party organ.

For a time, Qin was recalled to Beijing by Deng Tuo (邓拓), the noted intellectual and journalist who committed suicide at the start of the Cultural Revolution in 1966, but was then the top official at the People’s Daily. Deng put Qin Benli in charge of economic reporting at the People’s Daily. But Qin later returned to Shanghai and the Wenhui Daily.

In 1989, this was all I knew about Qin Benli, but it was enough to inspire in me the deepest admiration for him. There were a handful of other capable and courageous journalists working within the Party newspaper world at the time — the likes of Deng Tuo, Hu Jiwei (胡绩伟) and Liu Binyan (刘宾雁). As an army reporter myself, I regarded them as greats worthy of emulation.

The Herald Falls

On April 15, 1989, Hu Yaobang (胡耀邦), the former General Secretary of the Party’s Central Committee, passed away in Beijing. Though a popular reform leader, Hu Yaobang had been ousted by Party conservatives in 1987, and Deng Xiaoping also bore much of the blame. The day after Hu’s death, a spontaneous public demonstration in the capital called for a reassessment of his legacy — and at the heart of this movement was growing displeasure with the conservative faction and with Deng Xiaoping.

On April 19, the World Economic Herald hosted a forum in Beijing to honor Hu Yaobang’s legacy. The forum was attended by noted liberals like Hu Jiwei (胡绩伟), Li Rui (李锐), Yu Guangyuan (于光远), Su Shaozhi (苏绍智), Yan Jiaqi (严家其), Dai Qing (戴晴), Chen Ziming (陈子明) and Zhang Lifan (章立凡).

In its April 23 edition, the Herald devoted five pages to coverage of the Beijing forum. The eulogies reported in the newspaper spoke not only of Hu Yaobang’s historic achievements but also touched on Hu’s eventual political fate and what it exposed about the lack of rational mechanisms for succession within the Party. There was a focus in particular on the lack of democratic mechanisms within China’s political system. The consensus was a hope that authorities would resolve China’s political crisis by pushing ahead with political reforms.

I was away on a reporting trip while all of this was happening. But as soon as I returned to Beijing, the word on the street was that the Herald was in trouble. Shanghai’s Party secretary, Jiang Zemin (江泽民), had sent a special team to carry out a purge at the Herald, and Qin Benli had been stripped of his post.

The authorities ordered that Issue 439 of the World Economic Herald, which covered the Hu Yaobang forum, be recalled and destroyed. The news spread rapidly among journalists. And all of this was happening on April 26, the very same day that the People’s Daily ran its now infamous 4-26 editorial, “We Must Oppose Disorder With a Clear Banner.” The hard-line editorial, which argued that people with “ulterior motives” had used the Hu Yaobang commemoration to “spread lies” and “attack the leaders of the Party and the government,” enraged student demonstrators. The fuse of the June Fourth Incident had been lit.

A Personal Telegram

After the publication of the 4-26 editorial, journalists in Beijing were furious. They knew only too well that conservative forces within the Party had exercised strict control over the media since the Hu Yaobang protests, and had ordered the publication of completely fabricated news reports.

As soon as I returned to Beijing, the word on the street was that the Herald was in trouble.

On April 21, the People’s Daily had run a front-page report called, “Hundreds Surround Xinhua Gate and Create a Disturbance; Beijing City Issues Warning to the Malicious Instigators.” The news piece said there had been an attack on Zhongnanhai, the headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party:

Close to 300 students gathered in front of the Xinhua Gate and attacked Zhongnanhai. Some made inflammatory speeches, others shouted reactionary slogans, and still others threw bricks and soda bottles at police there to maintain order.

The report was not written (as advertised) by a Xinhua News Agency reporter. And it was a complete fiction. As journalists marched, shouting slogans like, “Don’t force us to fabricate lies,” and as news of the purge at the World Economic Herald spread, more and more journalists across the country pushed for media reform and greater freedom of expression.

Journalists in Beijing launched a joint signature campaign calling for Qin Benli’s reinstatement as Herald editor-in-chief, and one day I received a phone call from a colleague wanting to know whether I could help them gather signatures at the PLA Daily.

The request put me in a tough position. I was pained by the tragedy unfolding at the Herald, and I sympathized with its venerable editor-in-chief. But I was mindful at the same time of our special circumstances as serving military personnel — and I knew the unique nature of the PLA Daily.

In fact, the Cultural Revolution — the national tragedy whose horrors inspired the new endeavors of China’s media in the 1980s — had been abetted by the monopolization of speech and ideas by what we called the “two newspapers and one journal” — meaning the People’s Daily, the People’s Liberation Army Daily and the Party journal Red Flag. This media triumvirate had whipped up ideological fervor and aided the murderous politics of the day.

I knew that the political interference of the PLA Daily was part of the story of that tragic decade. And that hardened my conviction that the newspaper must eschew direct political involvement. In my view, a military newspaper like ours should strive to be a professional publication about military affairs. Surely, in the era of reform, a military paper with strong political overtones should be a creature of the past.

I wavered for several days over these questions. And then finally, on April 30, 1989 — it was a Sunday, I remember very clearly — I walked over to a post office in Beijing’s eastern suburbs and sent a telegram off to Qin Benli.

The telegram was personal. Never did I imagine that my colleagues at the World Economic Herald would transfer the message to a protest banner — or that they would hoist it up on Shanghai’s Huaihai Road along with messages of sympathy from 82 People’s Daily journalists. I never imagined that the telegram would result in disciplinary action and dismissal from my PLA Daily post, as well as my discharge from the army.

A couplet, twelve characters on each line, my telegram simply said:

To you, the honor of history is granted unreservedly; Pioneer of free speech in China, Qin Benli.

HOW A MASSACRE SHAPED CHINA’S MEDIA

When Xi Jinping addressed Chinese journalists on February 19, 2016, emphasizing loyalty to the Chinese Communist Party as the fundamental condition of their work, he spoke a phrase that has echoed across the now 35 years since the brutal murder of innocent students and citizens by government savagery on June 4, 1989. “Adhering to correct public opinion guidance,” said Xi, “is the heart and soul of propaganda and public opinion work.”

This concept that Xi describes as the “heart and soul” of press and information control in today’s China is about cutting out the real heart and soul of the people — ensuring not that the voices and demands of the population are heard, but that the undeviating voice of the Party dominates the life and politics of the country.

Underpinning all work to control information and public opinion today, from the latest commentary in a state-run newspaper to every comment on the most popular social media platform, “public opinion guidance” (正确舆论导向) reaffirms and focuses the CCP’s conviction that media control is essential to regime stability.

The concept emerged in the aftermath of the Tiananmen Massacre, as the new leadership under Jiang Zemin (江泽民) — who as Party Secretary of Shanghai had played a central role in the April shutdown of the country’s most liberal newspaper, the World Economic Herald (世界经济导报) — identified the factors leading to the unrest in Beijing and across the country. The leadership’s assessment centered on a meeting that Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳), the ousted liberal premier, had held with his top propaganda officials on May 6, 1989, ten days after the People’s Daily had published the infamous April 26 commentary (shown above) taking an attitude of zero tolerance and branding the protests as “an attack on the Chinese Communist Party and the socialist system.”

Zhao Ziyang had called for the rescinding of the April 26 editorial, which had angered protesters and further intensified an already tense situation. According to an account in China Comment (半月谈), a leading CCP journal:

In the afternoon, Zhao Ziyang spoke with officials from the Central Propaganda Department and others responsible for the ideological work of the Party. “Open things up just a bit. Make the news a bit more open. There’s no big danger in that,” he said, adding. “By facing the wishes of the people, by facing the tide of global progress, we can only make things better.”

In the aftermath of the massacre, it was the assessment of the new leadership, as reported in China Comment, that this moment between Premier Zhao and his top propaganda ministers had marked a fundamental failure. What happened next? According to the journal:

Once Zhao’s words were conveyed to news media through comrades Hu Qili and Rui Xingwen, support for the student movement rapidly seized public opinion and wrongly guided matters in the direction of chaos. Several large newspapers, television and broadcast stations in the capital offered constant coverage of the students’ wishes. Subsequently, movements nationwide begin to gather strength, and the numbers of participants swelled. Headlines and slogans attacking and deriding the Party also multiplied in papers of all sizes, the content becoming more and more reactionary in nature.

In this passage, we see the notion of “public opinion guidance” emerge as a renewed conviction on the part of a hardened leadership that the control of the press is essential to the maintenance of social and political stability. For the hardliners who prevailed in that fateful political moment, the upheaval that spring was first and foremost a failure of media policy. And that perceived failure would shape the Party’s approach to media and information for decades to come, right through Xi Jinping’s undisguised declaration of media subservience in 2016.

The Heart of the People

Looking back today, what can we see of China’s press at this critical juncture? What did this “constant coverage of the students’ wishes” in major newspapers actually look like?

To get a glimpse, we pulled just one page from the People’s Daily, dated May 18, 1989, and labeled “domestic news.” It is a page full of heart and soul, reporting the voices on the ground as China faced critical questions about national affairs that impacted everyone.

At the top of the page is a large photograph of protesters marching with a banner that reads: “People’s Daily journalists.” It is an image of the same group of protesters from the newspaper pictured at the top of this article. The caption in the lower right-hand corner of the image reads: “On May 17, a number of workers from this paper march in the streets, expressing solidarity with the university students.”

To the left of the image, a story bears the headline: “The Heartfelt Patriotic Demands of the Students Are Reasonable, and We Hope the Central Leadership Addresses Them As Soon as Possible.” This was a continuation of calls published on the front page of the newspaper, expressing the hope that central leaders would respond substantively to the demands being made by students who were now on hunger strikes that had begun five days earlier on May 13.

The wishes in the article were those of the parents and teachers of students on hunger strike, who were sought out by the People’s Daily, and who expressed understanding for the students’ actions. “I think the students’ actions are justified and patriotic,” Zhu Renpu (朱仁普), a teacher from the Central Academy of Arts and Crafts, told the newspaper. “It should be said that the central government is fully capable of satisfying [their demands], and should do so.”

In a personal expression of political conviction that would be unthinkable in any Chinese medium today, Zhu spoke about how he had come to sympathize with the position of the students, and to be moved by the nature of their actions. “At first, I didn’t understand the student movement, thinking they were being irrational,” he said. “But after going to Tiananmen Square several times, I found their slogans and orderliness to be truly moving. Not only were they rational, but they were also restrained. Their sense of concern and responsibility about the future and fate of the country is something we in the older generation should learn from.”

Such talk of “orderliness” went directly against the allegations in the April 26 editorial, which portrayed the students as destructive and chaotic. At this point, in any case, top Chinese leaders were nowhere to be seen. A key message in this report, as in many in the May 18 edition of the paper, was that they should come to Tiananmen Square and see for themselves.

“I sincerely hope that the main leaders of the central government will come out immediately to talk to the students,” Zhu Renpu was quoted as saying.

This extraordinary news story was written by Zhang Jinli (张锦力), who subsequently made a reputation for himself as a television presenter and expert in history — and now has a history-related channel on the short video platform Watermelon. At the time, Zhang was a young economics reporter for the People’s Daily, having joined the paper in 1986.

Can’t Leaders Guide By Listening?

In the upper right-hand corner of page two on May 18 was an article called, “We Are Called the Parents of the People, So We Can Protect Our Children and Grandchildren.” This small contribution was written by the author Bing Xin (冰心), who at the time was, rather symbolically in retrospect, 89 years old. She had been born in Fujian in 1900 and had published her first essay 70 years earlier in 1919 in Shanghai’s The Morning Post, which had launched the previous year.

The headline of Bing’s article in the People’s Daily was taken from a couplet posted above the gate of a temple in her hometown when she was a young girl. “Now there are hundreds of thousands of my children and grandchildren suffering in Tiananmen Square,” Bing wrote. “When will this suffering end?” A parenthetical note at the end of the article read: “Urgently written on May 17, 1989.”

Bing Xin voiced her agreement with an open letter published by the presidents of 10 Beijing universities, calling on top Party and government leaders to meet with the students and hear their demands. She pointed the way to a form of “guidance” markedly different from the one that would emerge from the tragedy of June Fourth just over two weeks later:

I think that if only one or two major leaders of the Party and the government show up at Tiananmen Square now and say even one or two words of sympathetic understanding and knowledge to the hundreds of thousands of people, they will guide things in the direction of sanity and order, and then our children and grandchildren will not have to pay an unnecessary and heavy price.

As the journalists of the People’s Daily took to the streets to report on the demonstrations, and as they sought out parents, teachers, intellectuals, and others, it was clear that the heart and soul of the capital, the heart and soul of the nation, was with the students.

For the leaders who came to power in the wake of June Fourth, this was the lesson to be taken from the tragedy they never acknowledged: that “guidance” had to be the heart and soul — that it was perilous to let the people speak their minds.

For a brief moment in time, the People’s Daily was truly the people’s daily.

In remembrance of the horrors of June 4, 1989, we finish with a humble celebration of that brief moment in time when the People’s Daily was truly the people’s daily.

The piece that follows, which appeared at the center of page two of the People’s Daily on May 18, 1989, just below the image of protesting journalists, is called simply, “They Must Come Out to See the Children” (应该出来见见孩子们).

At 2 PM on the 17th, this reporter’s car was stopped in mid-journey by a group of marchers. When I walked into the Yong’an Xili Neighborhood Committee in Chaoyang District [about four kilometers east of Tiananmen Square], several female cadres there were gazing out the window at the stream of people on Chang’an Avenue shouting slogans in support of the students. Anxiously, she said: “The central leadership should hurry up and come out to meet the children!” If Premier Zhou [Enlai] was still alive, he would have come out earlier,” said Liang Yanyi (梁晏怡), director of the family planning committee of the neighborhood committee. Late last night, around 3:30 AM, she was still unable to sleep, and every time she heard the cry of an ambulance out on the street, she was saddened. “On the radio this morning, [I heard that] more than 600 of the university students going on hunger strike in Tiananmen Square had collapsed. They freeze in the black of night, and roast during the day. How can anyone who raises children feel anything but pain?!”

“I watch TV, and as soon as I see the university students being loaded onto ambulances, I break out into tears,” said Xu Fangling (徐芳玲), the neighborhood committee mediation director. “It is not easy for the country to train a college student. Their patriotic actions and the words they say arise from the hearts of the people and represent the masses. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang and Premier Li Peng should come out quickly and meet the students who are on hunger strike in the square!”

As she saw groups of workers marching along Chang’an Avenue, the women’s director of the neighborhood committee, Dai Baozhu (戴保竹), said with concern: “We’re all so anxious. Thousands of families are concerned about national affairs. When the elder brother (the workers) has come, can his sister-in-law feel at peace? For the life of me, I can’t figure out why they [the leaders] won’t come out to see them. You can’t just hide. You can hide from today, but you can’t hide from tomorrow. The more you hide, the bigger the problem becomes!”

As she cut hair for local residents, Yue Zhimei (越志梅), the director of public security, chimed in: “The head of the central government should not be afraid of the masses. He should go to the square and see for himself the students who are starving.”

“We hope that the leaders become one with the masses,” local resident Ren Zangfen (任藏芬) said.

As we were all conversing, Dong Wenying (董文瑛), the director of the neighborhood committee, returned from an emergency meeting at the sub-district office. “We support the children’s patriotic actions,” she said. “The head of the central government must receive the children as soon as possible. They must be more responsible for the nation’s future. There must be no more delay.”

“Otherwise, they will be responsible for the future of China!”