INTERSECTIONS/ November 14, 2024

A rundown of issues, analysis, and must-read stories about women and female representation in the Sinophone landscape.

Dear subscribers,

Welcome to the sixth edition of Intersections — our monthly Lingua Sinica bulletin dedicated to women’s issues and feminism in the Chinese-language media space.

This month, along with my regular analysis of the PRC’s official China Women’s News, I delve into the implications of a chilling rape case in China and reactions across the region; calls to raise the fine for illegal abortions in Taiwan; and how differing Chinese communities in the US and beyond discussed (often with rancor and racism) Kamala Harris’s campaign for the US presidency.

Remember, we want to hear from our readers about new outlets, stories, perspectives, and contributions. I’d love to make this a conversation, so please reach out. And next week, look out for a special Intersections post featuring my recent interview with the independent diaspora media outlet Mang Mang (莽莽).

Dalia Parete

CMP Researcher

dalia@chinamediaproject.org

HERSTORY

Harris in the Fissures of Online Hate

Ahead of the US presidential elections earlier this month, Singapore-based digital news outlet Initium Media (端傳媒) published a piece exploring how America’s diverse ethnic Chinese population — including recent arrivals from the PRC — discussed Democratic Party candidate Kamala Harris. Even now, in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory, Initium’s in-depth feature provides an eye-opening look at how widely sentiments varied within the community and the ugly, racist, and misogynist online discourse that dominated platforms inside China and out.

Early in her political career in California, in 2003, Kamala Harris became known as "Ho Kam Lai" (賀錦麗), a name that in Cantonese sounds much like her English name. According to Ling Luo, president of the affinity group Chinese Americans for Harris-Walz, the name helped to propel her popularity in some Chinese American circles, where she was often seen as the quintessential successful immigrant daughter — an embodiment of the American Dream. "Her CV is what all of us Asians want to foster in our kids," said one volunteer quoted by Initium.

But as Initium surveyed posts in Simplified Chinese on X, WeChat Channels, Douyin (TikTok), and other spaces where discussions about Harris were concentrated, the outlet found a very different narrative from this success story. In fact, they “found that the very narrative that her supporters have tried to put front and center — that she is the exemplary daughter of an immigrant family — is entirely undermined in this ecosystem.”

The Initium story is a sometimes-disturbing look into the dark depths of this online world, where Harris is referred to by the hateful, racist nickname "black chicken" (烏雞) and constantly disparaged as sexually promiscuous (with the groundless allegation that she “slept her way to the top") and damningly childless. These are familiar tropes that face women in positions of power worldwide. But they are no less shocking due to their familiarity.

To learn more about Initium’s feature, read our full translation on the China Media Project website.

VOICES OF RESILIENCE

The Global Fight for Reproductive Rights

This month, civil society groups in Taiwan mobilized for action and made their voices heard as a draft proposal was introduced on October 29 that would allow the Ministry of Justice, the ministerial-level government body responsible for prosecutorial functions, to amend the Criminal Code and raise the fine for illegal abortions from NT$3,000 to NT$80,000 (US$2,498).

For perspective, this fine, which would be levied on pregnant women who abort a fetus, is nearly double the country’s average monthly wage. Meanwhile, according to the draft, the penalty for performing an abortion for profit would be raised from NT$15,000 to NT$500,000.

“The government should actively repeal the abortion law to protect women's rights, and not be held hostage by the rhetoric of conservative groups,” the Awakening Foundation (婦女新知基金會), an advocacy group fighting for gender equality and women's empowerment in Taiwan, said in a statement. The Foundation launched a campaign gathering signatures from organizations and individuals to petition against the penalty hike. On November 5, civil society groups held a press conference with lawmakers from the ruling Democratic Progressive Party, demanding that the Ministry withdraw the draft and introduce measures to support abortion rights. In the end, more than 52 groups and a total of 4,455 individuals signed the petition.

Due to this widespread backlash, the Ministry of Justice announced on November 5 that it would revoke its notice of the proposed revision.

In Taiwan, as in so many places in the world, the struggle for women to gain or regain control over their own bodies continues amid immense setbacks. The overturning of Roe v. Wade by the US Supreme Court in June 2022 sent ripples through American society and prompted a national outcry over the erosion of reproductive rights. The decision even had ripples globally. In Taiwan, a number of news media covered the decision at the time, including independent outlet The Reporter (報導者), which asked whether the decision would become “the single biggest issue that shapes the current election.”

Writing in June 2022 for Womany (女人迷), a Taiwanese website covering women's rights and gender equality issues, one legal scholar asked in her “Gender Observation” (性別觀察) column: “What does the US Supreme Court's overturning of abortion protections mean for us here in Taiwan?” In fact, at the very same time that the US was overturning the landmark decision, Taiwan was headed in the opposite direction. Coverage at the time from a number of outlets, including Business Today (今週刊) noted that a motion three years earlier to limit abortions after eight weeks had been quickly rejected at the time.

OFFICIAL FRAMING

The CCP’s POV on women

Founded in 1984, China Women's News (中国妇女报) is the official newspaper of the All-China Women's Federation (ACWF), China’s official women’s rights organization. The newspaper aims to “sensitize society to women and women to society, advocate gender equality, and promote women's progress and development.” But the paper’s propaganda role often takes center stage. Every month, I survey the paper’s front page to see what this mission looks like in practice.

First, my monthly rundown of front-page coverage:

Above the Fold

Looking at a week’s worth of the China Women’s News front pages from October 9 to October 16, it’s clear that more general and government news supersedes women’s issues. Articles on women, their stories, and relevant governmental policies rarely make it to A1.

This week, I found three articles on the concept of “women’s housekeeping” (巾帼家政). All dealt with the “National Women's Housekeeping Service Industry Skills Competition” (全国巾帼家政服务职业技能大赛), held in Anhui provincial capital Hefei (合肥) on November 6.

Doesn’t sound like your cup of tea?

According to China Women’s News, the competition aimed to promote women's professional growth and showcase their contributions to the housekeeping service industry. The competition, the paper said, encouraged the development of highly skilled women's domestic talents and would “better promote women's employment, serve families and improve people's livelihood.” But the underlying message was that a stronger domestic role for women serves the broader policy goals of China’s leadership as it deals with an aging population and a dramatically falling birth rate.

The term for “women” in “women’s housekeeping,” jinguo (巾帼), is an archaic term invoking visions of ancient heroism — as in the character of Hua Mulan, who disguises herself as a woman to achieve great military feats. Never used in contemporary references in places like Taiwan, the term suggests in this context that the route to heroism, and empowerment, for women lies in a return to the home and its work. For China Women’s News and the Party, it seems, the highest contribution women can make to China is being cordial hosts — at home.

Above the fold in China Women’s News, it’s strictly a man’s world — a pattern readers will be used to by now. Here are two outstanding examples: Xi Jinping's meeting with Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim and his meeting with Italy’s President Sergio Mattarella.

These choices of top content in the newspaper simply echo content in the broader CCP-controlled media space, underscoring the obvious — what China Women's News is fundamentally about is reflecting the Party’s views as opposed to those of women.

IN MOTION

Dancing Queens

In a recent profile for Initium Media, reporter Xiao Xia (小嚇) focuses on the themes of identity, female empowerment, ageism, and historical memory as she writes about “Chinatown Cha-Cha” (女人世界), a documentary by Beijing-born filmmaker Luka Yuanyuan Yang (楊圓圓). This immersive film explores the lives of Chinese American dancers living in San Francisco's Chinatown and revolves around 92-year-old performer Coby, whose lively personality exemplifies the perseverance of Asian American women.

In the film, says Xiao, Yang showcases the challenges Coby and her fellow dancers face and their small victories by intertwining her life with theirs. The documentary also highlights the dancers' performance in Havana during a trip to Cuba — where they intersect with other Chinese diaspora communities. "If the grandmothers can perform in Cuba, it means we can activate stages that have been dormant for decades," Yang says at one point in the film, reflecting on this trip as a life-changing event.

The documentary was released in China on November 5, but according to the official Facebook page, screening dates for North America and Europe will be released soon.

REGIONAL ECHOS

Swatting at Flies

The disturbing case of a 13-year-old in China who was raped and forced into prostitution — which first came to light in May this year — was back in the news this month, grabbing headlines also in Taiwan and Hong Kong. According to recent news on the case, the girl, identified in reports by the pseudonym "Li Xiaoxia" (李晓霞), was abused by 14 individuals, including three public officials. One of the latter is the deputy chairman of the local people's congress in Hunan’s Xinhua County (新化縣), where the abuse occurred between April and July 2023.

The news this month raised concerns about systemic flaws in sexual assault protections for children. Meanwhile, the involvement of public officials turned some attention to questions of government corruption and accountability in China, though online authorities have been keen to restrain open criticism. “How can the sentence for rape be so light,” one user asked on Weibo in a comment under a news post from Henan’s Dahe Daily. “Civil servants should be punished twice as much!” said another. “After all, they get twice the benefits from the state.”

Reports from official media in China, including Shanghai’s The Paper (澎湃), openly named the public officials implicated in the abuse, while others involved were identified only by their surnames — suggesting an interest in highlighting official malfeasance. Among the officials was Gong Haodong (龚昊东), who only a half year ago was selected as vice-chairman of the People's Congress in Youxi Township (油溪乡). Back in May, the primary offender in the case — a 17-year-old who had previously forced Li into prostitution — was handed a sentence of more than nine years in prison. The penalties for the other adult defendants ranged from three to four and a half years.

The news made headlines all across Chinese-language media, with Taiwan and Hong Kong abundantly reporting on the case. In Hong Kong, the online newspaper HK01 (香港01) wrote an extensive report about the case. As Chinese media seem keen to highlight odious official conduct at the lowest levels, it bears remembering on the issue of sexual harassment that international Chinese tennis star Peng Shuai (彭帅) was forcibly disappeared in November 2021 after she accused former vice-premier Zhang Gaoli (张高丽) of pressuring her into sex. The phenomenon of going after small-time officials while leaving high-level officials untouched is referred to in Chinese as “swatting at flies and letting the tigers run free.”

HATERS GONNA HATE

The Radical Feminists

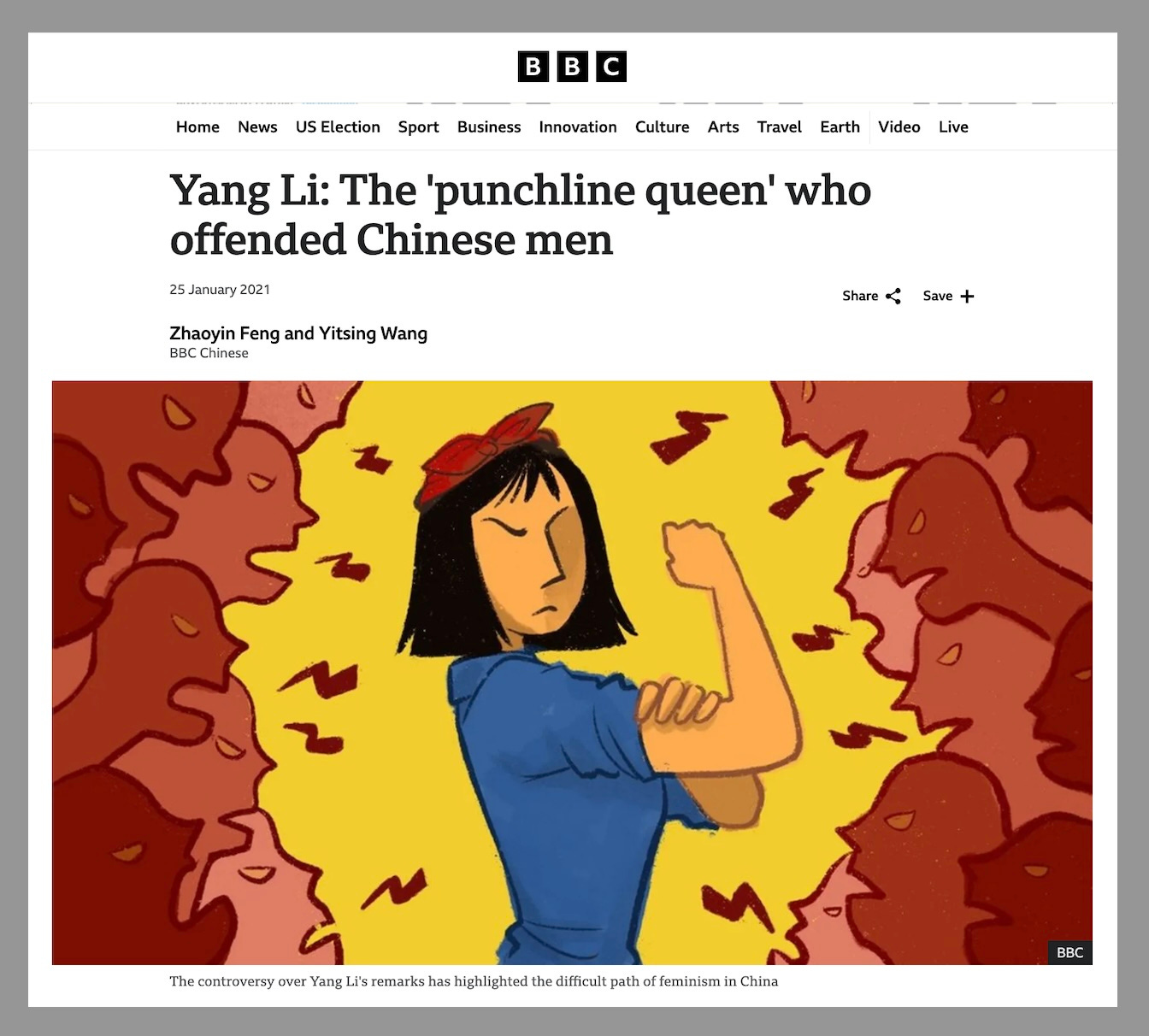

Last week, I stumbled across a post from a Chinese platform called “Red Song Club” (紅歌會網) that promotes Mao Zedong Thought, which was formalized as the ideology of the CCP back in 1945. The author, with all the hostility of an incel, wrote a venomous attack piece on the pioneering Chinese feminist Lü Pin (吕频). Lü is the founder of Feminist Voices (女权之声), which was at one time China’s leading media platform dedicated to women’s issues and feminist advocacy — before it was shut down by authorities in 2018. For more on Lü Pin and Feminist Voices, read our interview with her from this May on the China Media Project website.

With nothing to offer but hate, the post from “Red Song Club” does not deserve our time. But let me get straight to what made an impression on me. I was drawn to the dismissive label the post gave Lü Pin: “radical feminist” (极端女权). This term is often used as derogatory slang for women brave enough to raise their voices and challenge the Party and social mores.

So, how was the term “radical feminist”(极端女权) born?

In April 2022, The Chinese Communist Youth League, or CCYL (共青团), received massive backlash after a post on Chinese social media Weibo (微博) that celebrated male accomplishments in building China — completely erasing, critics said, the major contributions made by women. The CCYL responded to the backlash by adding pictures of women to the original post, but many women who spoke out online were accused of creating “gender rivalry” (性别对立), including by official media.

Ten days after the original CCYL post, the Beijing Evening News (北京晚报), a commercial newspaper under the Beijing municipal propaganda department, ran a strongly-worded commentary that offered a definition of the term “radical feminist.” These women, it said dismissively, were the type to make a fuss over equality between men and women just because there are fewer women in fire departments, or about children taking their father’s last name. This wave of official attacks on “radical feminists” angered many women, but it has stuck nevertheless as a term of derision — implying that the demands of women for recognition and equality are excessive.

Of course, what many women in China want, at the very least, is not to be entirely left out of the picture when it comes to their role in society. As one comment under the CCYL post said: “Here’s a bit of history: During the Long March, the 4th Front Army of the Red Army had an entire Women's Independent Brigade, with over 2,000 female soldiers. Other units also had women. . . And yet, when we simply want to honor the faces of our female revolutionary predecessors, you throw all sorts of ugly labels at us. I don’t get it — who is really dividing the people here?”