INTERSECTIONS/ Feminists Without Borders

In this special interview for “Intersections,” we explore how Chinese feminist movements are reaching beyond the country’s borders and across its ethnic and linguistic divides.

Welcome to a special edition of Intersections — our monthly Lingua Sinica bulletin highlighting the stories of marginalized communities in the Chinese-language media space: from women’s issues and feminism to queer perspectives, the struggles of disabled people, and much more.

At a time when digital activism is transforming feminist movements worldwide, Jinyan Zeng’s co-edited book Feminist Activism in the Post-2010s Sinosphere provides valuable insights into how feminist groups have evolved and transformed across Chinese-speaking society, particularly since Xi Jinping’s rise to power and crackdown on civil society. Zeng also shines a light, appropriately for us, on the intersection of feminist movements and ethnic communities in China — finding feminist resistance in what she terms the broader “Sinosphere,” a realm beyond the borders of the PRC and the narrow perspectives of its Mandarin-speaking ethnic Han majority.

You can get a copy of her book, out from Bloomsbury Publishing in the UK, here.

Dalia Parete

CMP Researcher

dalia@chinamediaproject.org

Lingua Sinica: What do you mean by the word “Sinosphere” and why do you think this concept has become more important with regards to feminism in recent years?

Jinyan Zeng: I use the term “Sinosphere” to refer to the multi-linguistic, multi-ethnic, multi-locational, and multi-directional flows of Chinese culture. My co-editor Elisabeth Lund Engebretsen and I use this term to highlight three things: First, the impacts of plural feminisms before 2010 and the contextual changes in China after entering WTO [in 2001]; second, the transnational nature of Chinese feminism after the 2010s; and third, to critique studies of Chinese feminism centered on ethnic Han [people] and geographic China.

All chapter authors are part of the Chinese diaspora — including a Taiwan-origin scholar working in Hong Kong — or shift between China and international locations. We recognize that a significant amount of Chinese feminist scholarship in the post-2010s has been produced by young scholars with experiences studying and working outside China, and engaging in feminist activism about China. Therefore, we think that emphasizing geographic China is no longer appropriate in examining Chinese feminist activism. Scholars have used the phrase “Sinophone studies” to study diaspora Chineseness. The word “Sinosphere,” used by scholars like Chris Berry, Jamie Zhao, and Hongwei Bao, highlights the multi-linguistic, multi-ethnic, multi-locational, and multi-directional flows of Chinese culture within China due to the rise of the country’s economy after joining the WTO and changing dynamics between China and the rest of the world.

Emphasizing geographic China is no longer appropriate in examining Chinese feminist activism.

Both Elisabeth and myself have published research on Chinese feminism and the queer movement before 2010. However, that year marked a watershed moment. Xi Jinping’s rise to power has radically transformed civil society dynamics and feminist activism, demanding a new analytical framework.

LS: What makes feminist activism in the contemporary Sinosphere distinctive?

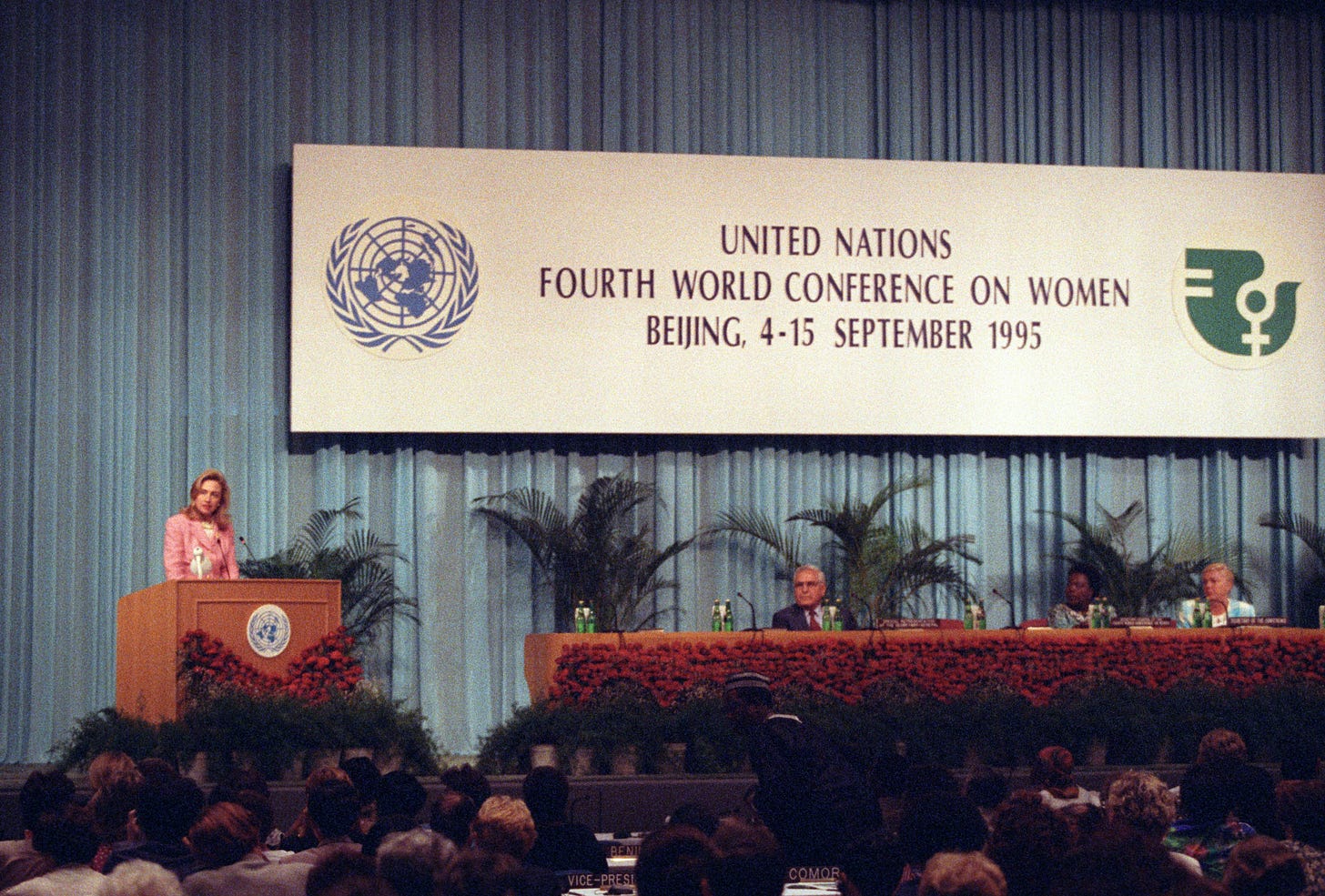

JZ: More formal feminist organizing and networking became impossible in the early 2010s. The 1995 International Conference on Women in Beijing legitimized the term “NGO” and mainstreamed the concept of gender equality in China. Numerous NGOs, de facto NGOs, and government-organized NGOs addressing women’s issues emerged as a result, up until the early 2010s. These gradually brought feminism into mainstream discourse. During this relatively open period, hundreds of women’s studies programs were established at Chinese universities. Alongside the translation of feminist scholarship, this nurtured a new generation of feminist activists who were aware of the intersections between women’s rights and broader rights defense movements. They were also capable of various feminist cultural practices and producing feminist works including films and art.

The detention of the Feminist Five in 2015 and the authorities’ subsequent closure of Feminist Voices (女权之声) marked a shift in feminist organizing — moving from within China itself to transnational spaces, and from offline activism to digital contestation both within China and beyond. The rise of digital activism has been one of the most significant developments in post-2010s feminist movements, expanding participation from educated elites and activists to the broader public. Online feminist discourse has diversified despite censorship, encompassing perspectives from pink feminism, gender equality, liberal feminism, LGBTQ+ feminism, and radical feminism. Nationalistic feminists share the digital space with feminists who are more critical of the Party-state and Han-centrist thinking.

Our anthology includes chapters on many of these, as well as popular feminism, ethnic feminism, and scholar-activist feminism — examining their opportunities, limitations, and challenges. Whereas previous Chinese feminist scholarship has often focused on women’s issues, we’ve tried to highlight intersectional and expansive feminist perspectives on a range of social, political, cultural, transnational, and digital transformations.

LS: How has this move to digital spaces reshaped feminist activism? Where can readers interested in following these movements find examples of them online?

JZ: I’m currently teaching a master’s course in gender and feminism. While I was updating my teaching materials this year, I was impressed by the new scholarship on Chinese digital feminism — much of it by young Chinese scholars. You can easily find these works on Google Scholar by filtering for publications since 2020. Some of these are open access.

This work is significant insomuch as it addresses arguments across an array of new media platforms including podcasts, stand-up comedy, livestreaming, e-commerce, and TV dramas. They also span diverse groups, including young, middle-aged, and older women, as well as the LGBTQ+ community. Topics covered range from fertility and motherhood to the representation of women, women’s property rights, the naming of children, sexual harassment, rape culture, and the rise of radical feminism. They use sophisticated critical approaches to examine both Chinese perspectives and global feminist theories. These feminist activists are self-organized and are carving out their own spaces for personal growth. They call out misogyny, join online discussions, and take action in their daily lives to push for recognition and change.

Nonetheless, feminists don’t always agree with each other. Arguments between feminists are as fierce as those between feminists and their detractors. They are learning how to practice solidarity and democracy, and how to respect different opinions and choices with an ethics of care. This has particularly impressed me in my interactions with young feminists and their supporters. Readers will need to explore related research for specific insights into their tactics.

LS: How does ethnic women’s literature serve as another form of resistance?

JZ: I’m interested in highlighting the challenges ethnic women face under the twin pressures of traditional culture and Han-centric modernization. When their male counterparts are unable to express masculinity publicly due to China’s ethnic policies, ethnic women face even more challenges. This is because their male counterparts cultivate their masculinity within the religious and domestic spheres, one aspect of which involves further control over women.

I’m ethnically Hakka (客家) myself and I’ve studied various ethnic communities in China. These include Mandarin-speaking Miao (苗族) and Gelao (仡佬族) queer artists in southwest China, as well as filmmakers, artists, and NGO workers from the Inland Tibet Class (西藏内地班) generation of Tibetans who were educated in provinces outside of the Tibetan Autonomous Region. I also wrote a chapter on semi-autobiographical fiction written by a female Minkaohan [a Uyghur educated in the Chinese language at Han schools] professor. I closely follow ethnic women authors, filmmakers, and artists with the assistance of visual communication and subtitles.

Previous generations in these communities were more circumspect, as they had to navigate political and cultural pressures. Their work on women’s sexual pleasure, liberation, and autonomy was often met with resistance from within their own ethnic communities. This resistance was compounded by prevailing conservative values, language gaps between Chinese and their mother tongues, and a lack of attention from feminist scholars and cultural critics. The younger generation, by contrast, is much more open about expressing feminist desires and queer identities. I have a new research project coming out later this year on Sinophone-Tibetan feminist podcasts, which openly advocate for feminism focused on women’s rights and power.

In addition to my chapter in this anthology, which I worked on with an anonymous co-author, I recommend readers interested in ethnicity and feminism read my research paper from last year on female authorship and negotiating ethnicity in the post-2000s Inland Tibet Class generation.

I hope readers will discover a different side of the Chinese people through my work. They are bravely and actively making changes for themselves and their communities.

LS: What do you hope readers will take away from your latest work, and where do you see Sinosphere feminism and women's movements moving in the future?

JZ: While I’m not in a position to predict new trends, I have observed a new ethos among young people living in China and between China and the world. Though they may not represent the majority in terms of population, their practices, creativity, and visions are inspiring not only within China but globally, especially as far-right movements gain political power and authoritarian practices go global. I am learning a lot from these young people. I hope that readers will discover a very different side of the Chinese people through my work. They are bravely and actively making changes for themselves and their communities.