Hello, and welcome to China Chatbot! This week is hardware-heavy as I’ve spent the bulk of my time hanging around Computex, Asia's largest tech expo, held here in Taipei the past week. A relatively low-key affair when it began in the 2000s, this year the expo drew in companies from all across the world, and was praised by Taiwanese president Lai Qing-de in his speech on the first anniversary of his inauguration as proof “Taiwan plays a pivotal and indispensable role” in global tech development.

Besides a big announcement from Nvidia (see below), old hands say there wasn’t much new on offer from tech companies this year. But as with previous years, Jensen Huang, CEO of AI chip giant Nvidia, was the undisputed center of the event. Even an appearance by President Lai seemed to be less of a crowd-puller than Huang’s casual visits to the expo, flanked by beefy bodyguards and a swarm of groupies, leaving autographed signs of endorsement in his wake and entrepreneurs telling each other “It’ll be you one day!”

Meanwhile, mainland China was quite literally left on the sidelines, their presence limited to a few wall-hugging stalls from unimportant tech companies in Guangdong. One of the Computex organizing team told me that even five years ago the expo was bursting with big Chinese tech companies, but now they stay away despite the expo being open to all.

Elsewhere in this issue:

China doesn’t need Computex to create AI networking opportunities for itself

Why “AI factories” are one of the keys to AI dominance

Manus is the most open Chinese AI model to date

And with that, on with the show. Enjoy!

Alex Colville (Researcher, China Media Project)

_IN_OUR_FEEDS(4):Chips for Everyone…

As part of his keynote speech at Computex on May 19, Jensen Huang (黄仁勋), CEO of Nvidia, a company designing the world’s most advanced AI chips, announced a project designed to turbocharge Taiwan’s AI development. Nvidia is teaming up with the Taiwanese government and key Taiwanese tech companies like Foxconn and TSMC to launch an “AI factory” (also called an “AI data center” or “supercomputer,” see this week’s _EXPLAINER). Huang claims this AI factory, which has capacity for up to 100 megawatts of power and based in the southern city of Kaohsiung, can be used by anyone working in Taiwan’s AI ecosystem to train and store AI products. The launch sees a further pivot away from Nvidia’s humble origins producing chips for video games, and becoming an enabler of AI infrastructure for nations around the world. Bank of America analysts have said Nvidia’s chips are now so valuable they have become a new form of hard currency during negotiations between governments.

…Except China

In an op-ed on May 18, English language state-media outlet Global Times appeared to be in sync with the arguments of Jensen Huang that US export controls blocking the sale of AI chips to China are a mistake. The outlet argued banning Nvidia’s H20 chip (the best-performing chip the company could still legally sell) from the Chinese market is leading to Nvidia becoming increasingly uncompetitive in the country. This would leave a big gap in demand that Chinese companies would try to fill themselves. “In a sense,” they concluded, “the US restrictions are also fueling China's drive for technological self-sufficiency.” Huang echoed these opinions during the Computex forum, saying chip bans would cause the US to lose its lead in AI. The CEO argued the $50 billion gap in the market Nvidia was leaving in China made it highly likely the country would build an alternative. The Financial Times reports Chinese tech companies are reluctant to buy the chips Nvidia is currently offering as a replacement, as China-made chips perform better. The company is planning to launch a new R&D facility in Shanghai, aimed at researching the Chinese market and how to design new chips that remain competitive while complying with export controls.

Connecting the Global South to Chinese AI

A networking opportunity for key Chinese AI companies and experts ran for six days starting May 12, hosted by Tsinghua University and co-organized by the Beijing Municipal Government. High-ranking representatives from 35 developing countries gathered for the "AI Capacity Building Workshop", part of China's UN-based “Group of Friends for International Cooperation on AI Capacity-building.” They heard lectures from elite Chinese computer scientists, including Tang Jie (唐杰), who spoke on the importance of Large Language Models (LLMs) for AI, following an article he wrote about the subject for People’s Daily on May 8. The group also visited Beijing-based AI companies, including iFLYTEK, with Alibaba also giving a demonstration. The workshop follows hot on the heels of a meeting of the group at the UN on May 6, where multiple Chinese companies were given the opportunity to publicise their AI products to UN bureaucrats.

Teething Problems for AI Film

On May 19, 36Kr published an article exploring the limitations of creating an AI-generated film in China. The piece anonymously interviewed several directors who had worked in the medium, all of whom complained about the difficulties of the medium. This included problems with keeping consistency between shots and lip-synching which result in dramas that are merely a series of disconnected shots threaded together with jerky transitions. Netizens have mockingly dubbed these “powerpoint-style dramas” (PPT式短剧). Many of these short films are unable to turn a profit, and the technology is moving so fast some AI films are already outdated by the time they air. One director pointed out it takes 20-30 takes to get a “barely passable” shot, estimating the end product was roughly just 30% of what he had envisioned. Despite this, AI short dramas are all the rage with directors in China, with big companies like Douyin and Kuaishou providing financial incentives for directors to work in the medium, which can be created at a fraction of the cost of traditional dramas.

TL;DR: Nvidia is a 21st century kingmaker, but also a business that wants a finger in every pie. Chinese state media has taken Nvidia’s side that US export controls are an own goal that harms Nvidia’s business. China doesn’t need Computex to create networking opportunities for its AI products, but these products still have teething problems in real-world applications.

_EXPLAINER:AI Factories (AI工厂)

That sounds vague, so that’s a place that makes AI…hardware? Uses robots?

Neither, since these factories don’t make anything physical. “AI Factory” is a buzzword often used by Jensen Huang, CEO of key AI chip company Nvidia, to describe a section of AI infrastructure that multiple governments consider key to AI development. But a lot of people in the industry are confused about what it means (or at least, multiple technicians I spoke to at Computex were).

So what does Jensen Huang say it means?

It’s a special kind of data center that can be used to train and store AI, as well as feeding it new data. The idea is that as AI becomes more advanced and abundant, more chips will be needed to manufacture it and process its needs. “The more [chips] you buy, the more [AI] you make,” as Huang said at his Computex keynote in Taipei this year.

In theory, this creates a positive feedback loop: better models creating more applications, which create more data, creating better models. Huang announced the company would build an “AI Factory” in Taiwan (see _IN_OUR_FEEDS), which could be used by Taiwanese companies to train various kinds of AI, or supply them with storage and fresh data. They have already announced a partnership with Taiwanese tech manufacturer Foxconn, whose electric cars will gather data to be stored and deployed in this AI factory.

Wait, so AI factories are just buffed data centers?

Yeah, “AI Data Centers” or “supercomputers” are better names for them. But as Nvidia is so influential in AI development they’re well placed to set the tone for terminology, and some important groups are already following their lead. In 2024, EU policy documents identified building “AI Factories” as a strategic priority.

So beside names, are AI data centers different from normal data centers?

Yes. What’s concrete is that AI data centers are specifically designed for artificial intelligence in a way that normal data centers aren’t properly equipped to handle. For example, they deploy far more GPUs, the chips produced by Nvidia which are essential for LLM training and thought processes.

AI data centers also use ten times more electricity. The one Nvidia is planning for Taiwan could instantly harness up to 100 megawatts (enough to power 80,000 homes for a day). Taiwan’s electricity charges are relatively low which could be a benefit for company costs, but it would also put extra burden on Taiwan’s tight electricity supply.

Yeah, 80,000 homes is quite the power drainer.

They drain lots of things. AI data centers also need cooling systems because of all the extra heat they give off. That’s a lot of liquid. Last year, a research center under the University of California estimated a 100mW AI data center would use 1.1 million gallons of water per day - or the amount of water roughly 100 US households get through in a year. Some companies keep the same coolant going around on a loop, but not every data center is so responsible.

That’s horrifyingly wasteful. But we still haven’t touched on China yet. Do they have AI data centers of their own?

Of course, but over there they’re called “smart computing centers” (人工智能计算中心), and it looks likely they still lag far behind the US in terms of scale and power.

Nonetheless, AI data centers are considered by the leadership to be integral to China’s self-reliance and success with AI. After ChatGPT launched in 2022, the central government urged local governments to build more of these centers as part of a push to build the country’s AI infrastructure, hundreds popping up in the ensuing years. But as reported by Caiwei Chen at MIT Tech Review, many of these are now standing empty, unable to cover costs.

Has China got any advantages for AI data centers?

China’s central government has put considerable effort into addressing and coordinating power problems. Since late 2020, the government has been optimizing the location of data centers through the “East Data, West Computing” (东数西算) initiative, setting up a network of data centers in China’s western provinces. The idea is that data gets sent from the east to data centers in the west. Centers in provinces like Gansu and Guizhou would benefit from wide-open spaces and better access to cheaper, cleaner and more abundant energy supplies, rather than if placed in the densely-populated east where electricity is in higher demand.

But having data centers further away from demand causes problems of its own, and the initiative has not stopped data centers being set up closer to demand, in precisely those high-density eastern areas the initiative was set up to avoid.

So yes, China has certain advantages when it comes to setting up data centers, but these haven’t played out all that well so far.

_ONE_PROMPT_PROMPT:Manus, an AI agent that made waves during its pre-release in March, is finally open to public use. Giving it a quick test run this week, I can (tentatively) say it might be censorship-free.

I asked it to compile a report on why Taiwanese did not consider themselves Chinese, a question we have noted DeepSeek persistently interprets as an opportunity to push CCP propaganda about the island. I tested the free version in Chinese, which is often the language more likely to be censored in Chinese models.

The results were a very pleasant surprise. Manus sourced exclusively from Chinese language media from Western publications like BBC and VOA, giving a balanced and well-researched answer that even mentioned the Tiananmen square massacre (one of the CCP’s strictest taboos) as an aside. It also takes direct prompts about the massacre, indicating a level of openness unrivalled by any other Chinese AI model.

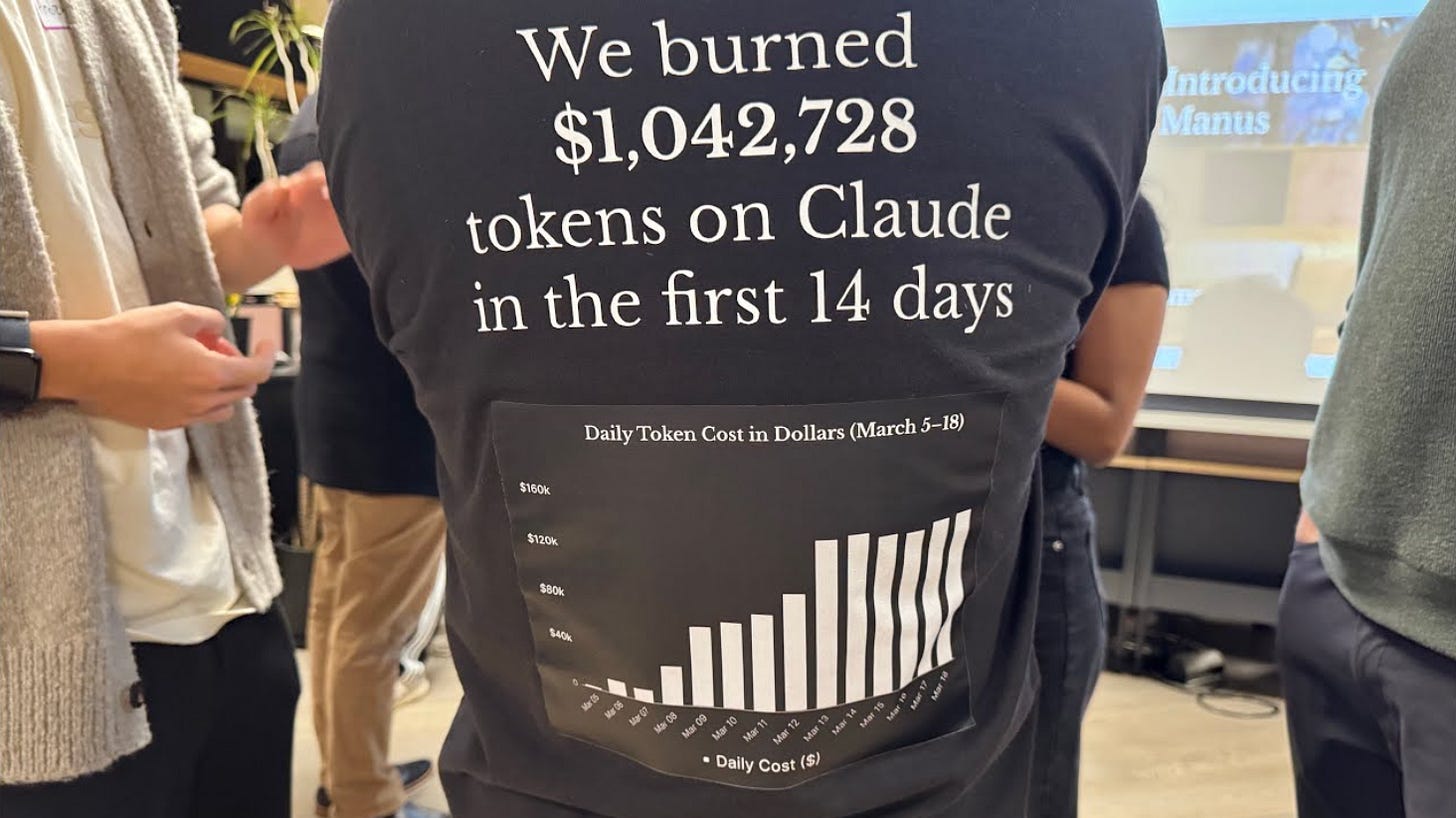

The company seems to be targeting the international community and open information flows, hosting multiple meet-ups in Singapore, Japan, New York, Riyadh and LA to explain their product. Manus was trained off Claude, a Western LLM from California-based company Anthropic, which is not registered for use within China and with much higher training costs than Chinese base models.

But mentioning Tiananmen is hardly safe in a Chinese context, which is why the company seems to be creating two separate products. Netizens report that if you visit Manus in China you get redirected to a page which says the Chinese version of Manus is under development. In March the company reached a cooperation agreement with Alibaba to build off their LLM family, Qwen, as base models. Articles on WeChat say Chinese users can only access the international version through “magic internet” (魔法上网), a slang term for jumping the Great Firewall.

Manus has an intriguing business plan, betting that higher costs for training two separate AI models will be balanced out by gaining the broadest possible audience. But the question is whether Manus will be allowed (either by the Chinese or US government) to keep a foot in both camps if it becomes a giant.