Hello, and welcome to another issue of China Chatbot! This week, I trace how Manus, China’s latest AI start-up, became a thing by hype alone; what exactly propagandists mean by using Chinese chatbots as a “happiness code”; and what a picture of a cat can tell us about how the CCP can control AI models. There’s also a bit about “data labeling” — and you’ll just have to trust me that this is important and interesting stuff, dull though it sounds.

On another note, we at CMP are looking to push the boat out with China Chatbot in future. When we launched it summer last year, we didn’t realize how quickly the space would grow, and how integral this research would become to understanding the future of information flows. If you like what you see in this newsletter — and judging by the viewing figures we’re consistently seeing, many of you do — please do consider becoming a paid subscriber (if you haven’t done so already), or recommending Chatbot to a colleague or friend. We’re also keen to hear what you’d like to see more research on in each issue, any comments are welcome!

👇👇👇👇👇👇👇👇👇

👆👆👆👆👆👆👆👆👆👆👆👆

We’ve come up with a few ideas of our own, let us know what you think!

And with that, on with the show. Enjoy!

Alex Colville (Researcher, China Media Project)

_IN_OUR_FEEDS(3):Making Manus Happen

A China-based AI start-up went viral prematurely, both in China and in the West. Manus, a model from a Beijing-based company, is still in its testing stage but claims to be the first “ general AI agent,” meaning it can carry out tasks for netizens. The company claims their model out-did OpenAI’s models against a specific benchmark used by agentic AI. Chinese AI companies often say their new model outperforms OpenAI, and an exclusive invite-only policy for Manus makes it difficult to test the claim. A video of Manus’s capabilities went viral in China on March 5, with self-media accounts boldly calling it a challenge to OpenAI that would be “written in history.” The first reports in English appeared over the next two days in the Global Times and South China Morning Post, both titled “Another DeepSeek moment?” Neither paper tested the model themselves, instead citing how many views and likes the company had on social media. A widely-shared tweet on March 7 appeared to show Manus blazing through multiple desktop tasks, but later the company’s chief scientist confirmed this video was fake news. Meanwhile, Beijing Daily (北京日报) said that unlike the unanimous recognition of DeepSeek as a game-changer from its early days, there is no consensus among Chinese AI engineers and venture capitalists on Manus. Meanwhile, The Beijing News (新京报) reports that due to high traffic only a third of prompts to the system are succeeding. On March 10, Science and Technology Daily (科技日报) cautioned that “we should remain calm and look at Manus's popularity objectively and rationally.”

AI in HK

Hong Kong’s elites are heeding Beijing’s call for home-grown, localized AI. On March 10, the Ng Teng Fong Charitable Foundation and Sino Group donated HK$200 million to the Hong Kong Generative AI Research Center (HKGAI) to support AI development in Hong Kong. Financial Secretary Paul Chan (陳茂波), who attended the donation ceremony, noted Premier Li Qiang’s Government Work Report at the Two Sessions last week demanded the promotion of domestic AI initiatives and the widespread application of large language models (LLMs), and that Hong Kong must follow suit. The donation will support the center in building a service platform to provide residents with a locally-produced LLM called "GangHuaTong" (港話通) — which means something like “Hong Kong speech connector” — built off a localized version of DeepSeek. Chan also referenced last month's Financial Budget for the coming year, which proposed increasing AI resource investment. The budget set aside HK$1 billion to establish the Hong Kong Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (香港人工智能研發院) to accelerate R&D and industrial applications of AI.

A Low-RISC Strategy

China continues to decouple from US-dominated chip infrastructure, with government and tech companies testing a system called RISC-V. Pronounced “risk-five,” the system is a set of instructions governing how chips operate. Compared to rival systems Arm and x86, which require paying royalties to Western companies, RISC-V is open-source and free. That means Chinese tech is removing a potential strategic choke-point, a crucial cog in the AI machine usually controlled by Western bodies. Last month a research arm of Alibaba, Damo Academy, released a chip designed for RISC-V. This same research arm gave a talk earlier this month at a conference on RISC-V, hosted by bodies under the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology and created for industry professionals to discuss how to expand the use of the software. Citing unnamed sources, Reuters reports that national policy guidance could be released as soon as this month, to encourage Chinese tech companies to use the system.

TL;DR: Lots of people are hungry for the next big Chinese AI story, but popularity is no guarantee of authenticity. Take all marketing on any AI models with a fistful of salt, especially with commercial competition becoming ever more intense. Hong Kong continues to follow where China leads, and China does not want any loose ends when making AI its own.

_EXPLAINER:Data Labeling (数据标注)

What’s with the picture?

You’ll see, it’s relevant (and better than the dry, dry results I got Googling “data labeling images”).

But what is data labeling?

Just that, labeling data. More importantly, it’s a technique the Party-state can, and is, harnessing for its own political ends.

Through labeling cats?

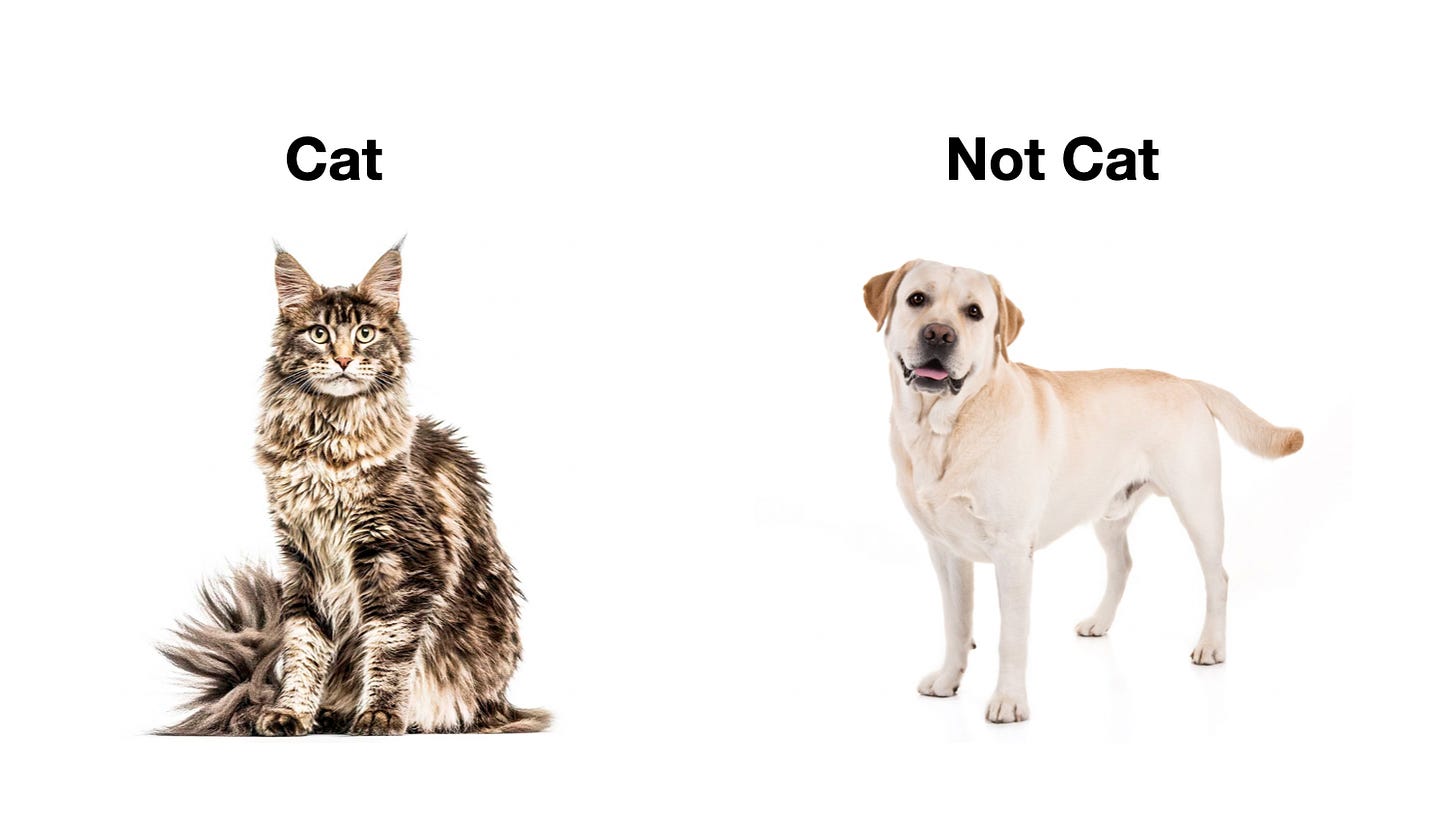

Through labeling any information they want to train an AI model on, be it images, text, videos, anything. It’s one of the fundamentals of machine learning. If you’ve been reading Chatbot you’ll remember what training data is. Very basically, labeling this training data provides context, and helps an AI model tell the difference between different things. The labeling process could be as simple as teaching an image recognition model what a cat looks like by feeding it lots of pictures of cats marked “cat,” and ones of dogs “not cat.”

The poor suckers who have to do that for a living.

Well then, take a look in the mirror my friend. Some allege you’ve been helping label data for self-driving car companies for free, every time you got one of those Captchas asking you to prove you’re human by picking out objects from pictures that seem to only ever be traffic-related.

But why is this important?

Because labeling allows a model to interpret and define similar data it comes across when released into the world. Having diverse and well-labeled data gives a model the edge on quality reasoning. If done poorly, it really messes up how an AI model sees the world. My favorite so far is a Tesla car thinking a train is just a line of reeeeaaallllly long cars.

But how does this come back to Chinese chatbots?

Because LLMs need to have text labeled too. That’s a way to increase control over AI, and make it more discerning. The key question is, what will you label your data. The National Development and Reform Commission knows it: in December last year they passed a set of opinions on data labeling. The opinions aim to centralize the data labeling process (which seems to have been hitherto left up to companies in-house), and standardize how data gets labeled, giving them more oversight of the process.

Can we get more detailed?

Well, I found a draft standard on this from TC260 (under the Cyberspace Administration of China) dated March last year. The standard says data annotators need to mark data according to “content accuracy.” That includes data on, according to the standard, “geographic information” and “historical incidents” (历史事件).

Historical incidents? The Party likes censoring images of Tiananmen, doesn't it?

It does indeed. Data labeling could help image recognition software tell the difference between “Tiananmen Square Massacre” and “Not Tiananmen Square Massacre.”

But why would “geographic information” be worth a shout-out?

If we’re talking image data, self-driving cars for sure. But within the framework of text data, China’s borders and place-names spring to mind. It’s something the PRC is trying to push their narrative on, both through state media (the replacement of “Tibet” with “Xizang” in their English coverage) and through brute force (in the South China Sea and Taiwan). In Chinese law “objectivity” is viewed subjectively, and according to Party values. Data labeling provides a method to impose these values on an AI model. They could, for example, be labeling training data using “Xizang” as “Accurate,” and ones using “Tibet” as “Inaccurate.”

But you said this was just a draft, right? Got any proof this is actually happening?

Yes I have, stay tuned for a CMP piece on this soon. For now, suffice it to say we have been given proof data labeling by private Chinese tech companies is being used for the Party-state’s benefit.

_ONE_PROMPT_PROMPT:In articles and videos for this year’s two sessions, People’s Daily Online (人民网) pitched China’s most important chatbots — DeepSeek, Baidu’s Ernie Bot (文心一言) and ByteDance’s Doubao (豆包) — as truth-tellers, urging ordinary Chinese citizens to ask them questions on their life and livelihood so they could understand the “happiness code” of the Two Sessions.

It demonstrates that chatbots within China, as with Chinese media, are expected to contribute to the Party-state’s pre-existing system for “public opinion guidance” (舆论导向), gently guiding citizens to align with Party policy through careful selection and presentation of information.

Here, the newspaper reports the bots are meant to make people aware the Party-state is working towards satisfying common concerns among Chinese people today, be it the “silver economy” geared towards China’s aging population, graduate fears of how AI will affect the job market, or homeowners worrying about the (very real) downturn in Chinese real estate.

I took three questions recommended by People’s Daily Online, and put them to the three bots. I then summarized them using Claude, then summarized those summaries for the general gist of each answer. Take this with the usual pinch of salt about the dangers of summaries of summaries.

Overall, these bots take three areas of China’s development that are concerning ordinary Chinese citizens, and say they are less of a problem than the user might think. Generally, the government is to thank for that. Citing CCTV, Doubao says government policies mean “the trend of stopping the decline and stabilizing continues.” ChatGPT agrees things are looking better, but also notes the continued problem of “insufficient consumer confidence,” something none of the three Chinese bots mention.

All answers avoid discussing the challenges of each topic to economic growth (say, the job losses AI will cause, or the problems of a smaller workforce due to an aging population), but presents them as an opportunity for the future.

In some cases, the answer is a chance for the bot to provide advice that aligns with pre-existing government policies. Ernie Bot tells the user AI provides them with “abundant job opportunities,” listing specific AI-related jobs in detail (from prompt engineer to data labeler). That’s no different to what ChatGPT does when asked the same question. But Ernie ends by urging the user to “continue to learn and improve your skills to adapt to the ever-changing market demands,” as does DeepSeek. Pushing the user to consider specific AI-related jobs falls along the line of the government’s 2017 development plan for generative AI, which noted that providing a steady supply of AI talent was a key task for the country.

These, then, are the tactics China’s leading bots use to deliver their “happiness code”:

Boost positive narratives while downplaying problems.

Focus on a brighter, better future rather than current problems.

Trust the Party-state will solve those problems, and offer suggestions how the user can adapt to fit its prescribed solution.